[youtube id=”UBF4ADu9YEM” align=”center” mode=”normal” autoplay=”no” aspect_ratio=”480″ maxwidth=”640″]

Defining Difference

Video[youtube id=”7X9JzEvuiGY” align=”center” mode=”normal” autoplay=”no” aspect_ratio=”720″ maxwidth=”1280″]

Impact of Colonization

Michael Epley

KNW 2399

April 30, 2015

Ball-Phillips

Impact on Colonization

India has a long history of mixed culture, views, and who’s in power. Great Britain colonized India and forced a culture shock from day one. The impact left by Great Britain will stay with India’s culture forever. The caste system will always leave an impact on Indian history and future. Life in India before Great Britain colonized it was very traditional lifestyle. Things in India were much simpler compared to when Great Britain came along. In the broad study of colonization throughout all of history, the relationship between cultural practices and violence is seldom discussed. But, when looking at the colonization of India and Southwest America/ Mexico is something you have to look at because it is so apparent and very repetitive.

Culture and Development Defined by Colonialism

Video[youtube id=”8QGMYmDLCrI” align=”center” mode=”normal” autoplay=”yes”]

Part I Visual Cultures Project (resubmitted)

Lily and Parbhoo Children

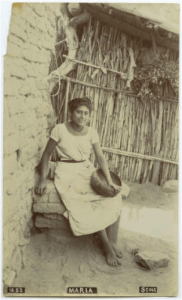

Lily by Winfield Scott shows a young Mexican girl in a white rough-spun tunic posed on a balustrade and leaning against a pillar, with one leg crossed in front of her and the other hanging off the side. Her left hand rests on her hip, while her right hand loosely holds what appears to be a white rose. Around her are two wicker baskets, one empty, and one filled with stalks. Judging from her clothing and surroundings, she appears to be impoverished; she wears no jewelry, and the wicker baskets demonstrate she is likely working despite her age. The two most interesting aspects of the photograph are in Lily’s demeanor. It is unclear as to whether she is posing or was positioned, but in either case it is a visual oxymoron: she is wearing white, holding a white rose, and yet she still looks provocative. This juxtaposition brings to mind La Malinche, and confliction as the mother of the people—is she treacherous, or a victim? Lily stares directly at the photographer, with her head held up and tilted to the side. Her demeanor indicates pride, resilience, but not hope; she is stuck in this world on her own.

http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/mex/id/663/rec/1

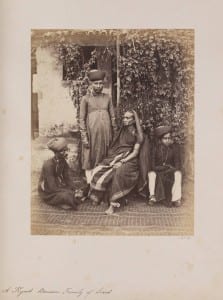

Parbhoo Children by William Johnson shows four wealthy children, positioned on and around a balustrade. The children are obviously wealthy from their clothing, which is adorned with jewelry. Three children are looking at the camera, but one is looking to her left at her peers, who are likely her siblings. The interesting aspects of this photograph are the demeanors of the children; each looks sad and servile, as though they are trapped. This is notable as they are children of wealth. The children are dark of skin, and the photograph is taken in the height of the British occupation of India, so this concept of being trapped weighs heavily and serves to remind the viewer of their situation: wealth means little when the subjects are oppressed by a colonial imperial power. They may be members of a high caste, but are still lower than any white person.

http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/eaa/id/776/rec/32

The Justification of a Nation

Austin Eckhout

Edges of Empire

Ball-Phillips

April 30, 2015

The Justification of a Nation

As we look into the history books regarding the colonization of various native peoples, we see that there is no shortage of photographs and paintings regarding those that were colonized by European empires. Photographs, although presumed to always show the truth of a situation and perceived as more factual than a painting, can still be manipulated so that a biased opinion may be displayed for the viewer. In today’s era of technological advances and photoshopped beauty queens, we are much more aware of the fact that we cannot simply believe what we see. However, the Conquistadors and British Colonizers, of Mexico and India respectively, did not have access to anything this far advanced in terms of photography. Instead, photographs were manipulated prior to their capture. Through examination and analysis of these subtle manipulations, we are able to see the goals these colonizers had in terms of propaganda via photography. Through their images, photographers for both the English and Spanish empires were able to display the native peoples of their colonies as being less developed than Europeans. They portrayed these colonized people as being primitive by comparison in order to justify the colonization of these natives.

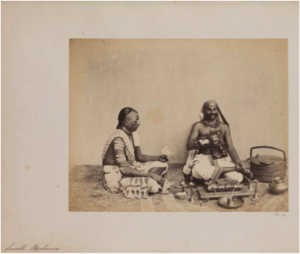

As you can imagine, many in Europe saw the colonization of natives in India as a controversial action. There are numerous reasons for one to view the complete takeover of a country and its people as being something to stand opposed to. A large part of what the British did in India was not simply the taking of land, but the complete reformation of the Indian lifestyle. During their colonization of India, the British forced their newly colonized people to convert to Christianity, as well as change and do away with many of their cultural practices. As with any major power, the British used various forms of propaganda to ensure that British citizens sided with their government. One of the strongest platforms on which the British government justified their colonization of India was photography. Photographs were used to display the Indian people in a number of ways. One of such idea was that of the Indian native being less developed, or civilized as a European. In the image below, we see two Indian men seated in traditional dress.

At first glance, this photograph seems to simply show two native men of India, seated and perhaps having conversation. However, it is through further examination that we uncover the suggestions of the photographer about these men.

Almost instantaneously, we see the attire of these men that any European at the time would view as peculiar. This trait alone does not label the men as being primitive or uncivilized. Upon a second look, we see that the man on the left has his skin painted. The face and body paint strongly resembles what would be seen as tribal markings. The man’s body paint, creating an idea of him being in a tribe, help to enforce that idea that the British government desired to portray to their citizens about Indian people. To add to the tribal portrayal of these two men, we have them seated cross-legged on the floor, unlike Europeans who sat in chairs. Though a small part of the photo, the idea of sitting on the floor would not be common in Europe and would be believed primitive.

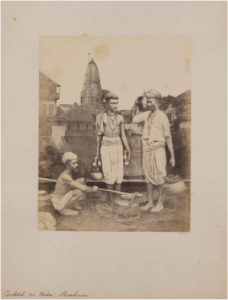

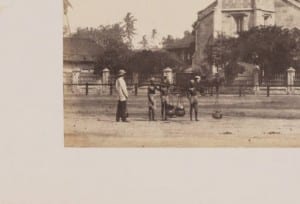

In this image we see another display of Indian men in a way that depicts them as being less developed than the people of Europe. Similarly to the first photograph shown, these men are in traditional Indian attire. The two men on the left both have their torsos exposed, a practice that was seen as socially unacceptable in Europe and would cause viewers to think these men as being uncivilized in that their exposed upper bodies would not be tolerated in Europe. The three men appear to be collecting water, a practice that was no longer common in Europe, as technological advancements had made it unnecessary. This fact instills the idea that the people of India were far less advanced as a society, and therefore justified colonization through the belief that British involvement in the development of India would be beneficial to the native people, bringing them modern practices that would make their lives more acceptable by European standards. In the background of this image, we also see the living conditions of Indians. While, to us, these houses would seem fairly nice compared to what we know now to be the condition of modern India, these homes would be very simplistic compared to the homes in Europe. Their simplistic robes, coupled with their lack of modern conveniences and underdeveloped homes, further strengthen the idea that British colonization of India would be beneficial to the natives. The British government uses this idea to push its citizens towards the thought that not only are they justified in colonizing India, but that they also have a moral obligation to help advance the Indian people towards a lifestyle that had the comforts and modern “necessities” of Europe.

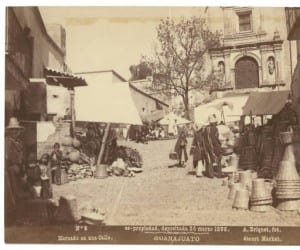

We turn our attention now to the Spanish colonization of Mexico and its native people. Unlike with the British in India, the Spanish faced different challenges in their conquest of Mexico. Conquistadors were not as lucky as the British with their colonization as they came across natives that were more resistant to colonization than those of India. While it is true that the Indians opposed their British rulers, the natives of Mexico rebelled much more and, being constantly at war with each other, were far more practiced in armed battle. The Spanish did not only find them selves fighting against the natives of Mexico, but also against the opinions of those back in Spain. To counter this, the Spanish government made use of the same tactic applied by the British. Among a number of incentives given by the Spanish government to persuade the Spanish people into supporting and joining in on the colonization of Mexico, they also used photographic propaganda to remind those in Spain that their presence in Mexico was both justified and necessary. Just as the British had, the Spanish were sure to depict the natives of Mexico as being primitive and uncivilized, as well as showing them to be heathens, having practices that were believed to be sinful in Christianity.

In the image pictured, we see a mother breast-feeding her child while two girls and a boy are seated in a line checking each other’s hair. Of course the first part of the photo that we see as being unordinary is the mother openly breast-feeding her child, but for now we will address the other aspects of the image. The setting of the photo, to a Spaniard, would be seen as below their standards of living. The ground that they are seated on is nothing but dirt and the wall of the house next to them is roofed by little more than grass. At the time, a home with grass for a roof would be viewed as underdeveloped with the advanced homes in Europe. A European also would see the collection of baskets and vases around them as odd. To keep your belongings outside and uncovered is another practice that would be primitive in Europe and therefore shows these natives to be primitive as well. Addressing the woman breast-feeding her child in the street, this is an act that would be seen as highly unacceptable by Europeans. Just as in our modern times, public nudity was not seen as something that should be allowed in Europe. For a woman to expose herself outside of her home was unheard of for modern Spaniards. All of the aspects of the photo support the idea of the native Mexicans being beneath their European rulers. The simple and underdeveloped condition of the home and uncivilized actions of the natives help to grow, in the minds of those still in Europe, the idea that Spanish rule in Mexico would result in a more developed and advanced society that would be seen as acceptable to the Spanish, who would grow to believe that it is their duty to help the natives of this colony to become more civilized.

In this photograph we have another example of a native of Mexico being displayed as less developed than the people of Europe. Starting with the setting of the image, we see that once again, the ground is only dirt and sand. In the background, there is a wall made only of branches and small trees. The combination of the wall and the dirt on which the subject is standing suggest a Mexico that is in disrepair and requires outside help.

The woman that is the subject of the photograph is not entirely unusual from a European standpoint. However, her lack of shoes while outside in the dirt can be seen as a representation of her not being a woman that has much. For Europeans, shoes were commonplace and, more likely, expected to be worn, especially when outside. She is seated on what appears to be a makeshift seat protruding from a wall of stone. This seat of hers is neither well made, nor does it resemble what a European would consider a seat. The wall and the seat jutting out from it appear to be falling apart almost and suggest a lack of engineering development in the society of Mexico. These living conditions would not be befitting of a European and, since the Spanish had so much to give in terms of advances in civilization, they were required to assist the natives of this colony in their development towards a more “European” society. This so-called “white man’s burden” served as a strong foundation for the Spanish conquistadors to justify their settling of Mexico.

Though their colonies were on opposite sides of the world, both the British and Spanish Empires faced similar difficulties in their colonial efforts. These problems were not only found in the natives that they were colonizing, but also rose up in the motherlands of these two empires. The moral disagreements held by Europeans towards colonization of the Indian and Mexican were handled the same by both colonial powers. To counter these beliefs of colonization being wrong, the Spanish Conquistadors and British colonizers both used photography as a form of propaganda. Through this platform, these two nations were able to justify their take over of India and Mexico by creating the idea that they were obligated to help develop the natives into civilized cultures.

Bibliography

Guha, Ranajit. Dominance Without Hegemony: History and Power in Colonial India. United States of America, Harvard College. 1997. Print.

Trivedi, Harish. India, England, France: A (Post-) Colonial Translation Triangle. University of Montreal. 1997. Print.

Pren, Hanns J. Spanish Colonization and Indian Property in Central Mexico, 1521-1620. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 1992. Web.

Wood, Stephanie. Transcending Conquest: Nahua Views of Spanish Colonial Mexico. University of Oklahoma. 2003. Print.

Jackson, Robert H.; Castillo, Edward. Indians, Franciscans, and Spanish Colonization: The Impact of the Mission System on California Indians. University of New Mexico. 1995. Print.

Photographs

http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/eaa/id/711/rec/5

http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/eaa/id/710/rec/4

http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/mex/id/667/rec/5

http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/mex/id/671/rec/9

Doing God’s Work

Doing God’s Work

If God told you that it was your right, your duty, to conquer the lesser people of the world would you do it without remorse? What if instead of God saying this directly it were your king, who claims authority by divine right? What if you just desired an empire and used these two scenarios as justification? This was the case for Spanish colonization effort in Mexico and the British colonization in India, they both claimed that they wanted to create their massive empire based on the exploitation of the natives to “Honor God”[1]. The pictures in this article serve the purpose of showing the contrast in the extent that each empire used religion as a tool to control and justify their colonization efforts.

Spain put much more of a focus on religious conversion from the beginning of their presence in North America. Just a soon as Columbus stepped on the beaches of the Bahamas so too did the thought of large scale conquest in the name of Spain. The Spanish arrived in the New World originally searching for a short cut to India so that they could trade faster and make their empire richer faster, however, once the Spanish realized that they were not dealing with the relatively advanced Indian empire and they were dealing with a comparatively primitive civilization the thoughts of military conquest were hatched in their minds. They saw their obvious technological advantages and took note that the natives already treated them like God’s adorning them with vast amounts of gold and silver; the temptation was too much.[2]

Surprisingly, the Spanish began their conquest of the Caribbean by laws and treaties. The issue of legitimacy of these signings was settled in probably the best example of asymmetric information that has happened in human history. The Spanish claimed that the natives, all coming from different tribes with different dialects let alone languages, willingly signed themselves into indentured servitude after the Spanish translator read out the laws to groups of the natives, after which they would line up and sign. This was done to bring glory to God’s name, obviously. For the most part this seemed to work, but when it did not work the populations got to see what Spanish steel and lead could do, sometimes resulting in the loss of entire populations of natives from islands, which seemed counterproductive to their stated goal.

The goal of the Spanish conquest was to bring glory to god’s name and get rich[3]. The order does not necessarily reflect importance. One might ask unreasonable questions such as “How does getting natives to sign away their land and rights bring glory to God’s name?” well the answer to that is: because they are in debt to the Spanish because the Spanish ever so kindly agreed to convert them into Catholics. The laws and treaties that the natives had to sign stated that they were going be converting all of them so that they did not burn eternally in the depths of hell. But in order to ease the process of having to go out and find the natives they would keep them on these “encomiendas” where they could more easily teach them the ways of how to become a good catholic. As payback for the Spanish helping them out in the afterlife they would work fields around the encomienda. This last little detail helps explain part two of the Spanish’s goal: get rich.

The conquistadors came from Spain, across the ocean, discovered the other side of the planet, and after Cortez came through, conquered the most advanced civilization at the time, so they wanted rewards. Coming from Europe, where the only thing that matters is title, they felt that they had earned one. After Cortez and his men toppled the Aztecs they established the encomienda system in current day Mexico. The system in Mexico was not only agriculturally based like in the Caribbean because Mexico has one important resource and a lot of it: silver. After finding out that they could mine tons of silver from the land, the Spanish suddenly felt the Holy Spirit flowing through them and just had to give it to the natives. This is when the system stopped looking so much like a humanitarian effort and started looking like horribly abusive system of enslavement. The abuses of the Spanish were documented in book that shook the world called “A Short Account of the Devastation of the Indies” which was written by a Spanish Friar named Bartolome de las Casas[4]. The book was actually written because Bartolome thought that God would punish the Spanish for the atrocities that they committed against the natives. So it seems as though in the quest of riches they left out the first half of their stated goal.

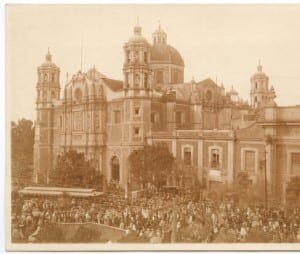

The photo of the Basilica of our Lady Guadalupe embodies many of the themes that appear in the history of the colonization of Mexico by the Spanish. What stands out the most is the size of the cathedral in comparison to everything in its surroundings. The size in the photo shows that it is the main focus of the picture, which is similar to how throughout the colonization effort it was maintained that religion was the main focus. Upon closer inspection of the photo one can make out there is a market place directly in front of the Cathedral with a massive crowd surrounding them both.

The photo of the Basilica of our Lady Guadalupe embodies many of the themes that appear in the history of the colonization of Mexico by the Spanish. What stands out the most is the size of the cathedral in comparison to everything in its surroundings. The size in the photo shows that it is the main focus of the picture, which is similar to how throughout the colonization effort it was maintained that religion was the main focus. Upon closer inspection of the photo one can make out there is a market place directly in front of the Cathedral with a massive crowd surrounding them both.  The market is the second part of the goal of the Spanish, to get rich, but at expense of the natives which is seen as the crowd coming to give there money to the few shop owners. The extravagant design of the cathedral is shows how much time and money was put into its construction, similar to how the religious justification of colonization took a lot of effort to create and maintain. Even in this ground level picture of the market you can see the edges of the cathedral. What tells the most about the conquest of the Spanish over the native peoples is the fact that this cathedral is in Mexico City, which used to be the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan. The cathedral in this city is like flying a permanent flag over the capitol of the Aztecs.

The market is the second part of the goal of the Spanish, to get rich, but at expense of the natives which is seen as the crowd coming to give there money to the few shop owners. The extravagant design of the cathedral is shows how much time and money was put into its construction, similar to how the religious justification of colonization took a lot of effort to create and maintain. Even in this ground level picture of the market you can see the edges of the cathedral. What tells the most about the conquest of the Spanish over the native peoples is the fact that this cathedral is in Mexico City, which used to be the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan. The cathedral in this city is like flying a permanent flag over the capitol of the Aztecs.

India was not a newly discovered land to its colonizers, so the strategies for colonization were not identical, but similar in justification as the Spanish colonization effort. India was already know to the European powers as a rich far away land that produced great textiles and spices among other luxury items. The first effort to colonize India was by the Portuguese. The Portuguese discovered the Cape of Good Hope can be navigated in 1488, which is very close to the Papal Edict of 1493 that demanded mass conversions into Catholics. They strayed on land for a little in search of Christians, and began converting for a little while. They establish a monopoly on the trade route around the cape and in the Indian Ocean with a system of licenses and their superior firepower over the Moghal navy. The British established their place in the Indian Ocean world after the Portuguese’s folly of monopolizing only pepper for trade without account for economic principals of supply and demand: they created a surplus in Europe and the price tanked. At first the British came in the form of a multinational corporation, the East India Company[5]. This strays from the arching theme of religion as a justification, however, it is quite clear that the goal of making money is clearly there. Most of their influence was in Bengal and they strengthen the cities Madras, Bombay, and Calcutta with their trade and presence. The big momentum change as to who controlled India came at in 1757 after the Battle of Plassey when the East India Company defeated the Mughal Empire and France[6]. While this was not a complete defeat of the empire it certainly weakened it, and lead to the decentralization of it. From this point on the British had the power of taxation.

The power of taxation was the secret to the British’s success. They gained power by taxing Indians they had conquered and that tax money went to training the newly conquered into an army. This new army would then go and conquer more land, and then repeat. One might ask why the British did not face many uprisings if they were clearly expanding at a rapid pace, and taking control of different cultures in a short time. Well it is because they were not forcing their own beliefs on the natives. No, the British did not use their own religion as a justification for rule, they used the Indian’s own religion as justification.

Hindu was the main religion of the area and the numbers of Hindus vastly outnumbered the number of Christian British, so how did such small numbers of people gain such control? Well the British had been in the colony game for a while, and if anyone knew how to rule from behind the scenes it was them. The British read all the Holy Books of Hindu, the Vedas, and although at the time it was mostly an oral and localized religion they used the structure in the Vedas to control the area. They found a system that favored elites, the caste system.

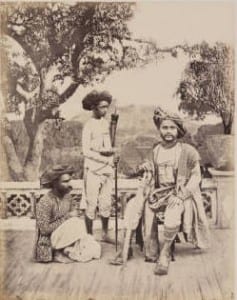

The British and the Indian elites were the only people allowed to read the Holy Texts; the next most powerful caste was the warrior caste. With the rich and powerful happy and in control of the warriors the British just had to benefit the elites without real threat of an uprising, or at least from the Hindu. In the above photo there is a picture of a local elite and his two servants. The photo seems to be an attempted portrait of the Chief, which explains his formal wear and pose. The servants in the photo look as though they

There were other people who practiced different religions who did not quite please the British, such as the Thuggies. These people were notorious highwaymen and the British did not want to deal with Hindus not part taking in the caste system, so they started a vicious campaign to show them as death worshipers and started to kill them in large numbers. While this was justified by saying it was for safety, which it did help, it was also a show of the intolerance of the British towards people who did not want to fall into their control system. What justified the British’s seemingly remorseless intolerance of people who would not just roll over to their domination?

The British had obviously set out to make money, but how did they morally justify their actions? Quite simply the British declared them too easy to rule, almost as if it were their right to rule them. Alexander Dow in 1770 stated that due to the climate and culture the natives are inclined “to indolence and ease; and think the evils of despotism less severe than the labor of being free”.[7] Dow is claiming that they have become lazy to the point that they do not care if they are ruled if it means they don’t have to do anything. Another perhaps clearer opinion comes from Thomas Macaulay who believes that “There never, perhaps, existed a people so thoroughly fitted by nature and by habit for a foreign yoke”.[8] He agrees with Dow that it is the climate that affects the habits of the natives, but mostly focuses on how feeble and effeminate they are in comparison to the British. This idea of British superiority was later justified when race science and racism came onto the scene in the 19th century. These ideas seem to match the ideas of “The White Man’s Burden” which preached it was the responsibility of the whites to rule over the “lesser” races.

The photo here shows a man watching over three Indian men doing work in front of a church in India. The interesting thing about this photo is that they quite literally have the yokes of a foreigner on their backs. Probably the best example of what Macaulay was claiming. The church stands in the distance, much like how the British distanced themselves from the church as the reason for their imperialism. One cannot tell if the man with his back turned is British or Indian himself, but in either case it shows how the British ruled over India: sometimes upfront, sometimes using the local elites to do their work.

The photo here shows a man watching over three Indian men doing work in front of a church in India. The interesting thing about this photo is that they quite literally have the yokes of a foreigner on their backs. Probably the best example of what Macaulay was claiming. The church stands in the distance, much like how the British distanced themselves from the church as the reason for their imperialism. One cannot tell if the man with his back turned is British or Indian himself, but in either case it shows how the British ruled over India: sometimes upfront, sometimes using the local elites to do their work.

[1] Bauer, Ralph (2001). Finding colonial Americas: essays honoring J.A. Leo Lemay. University of Delaware Press. p. 35

[2] Golden, Brenda (2010-08-24). “A Native Take on Terrorism, the Towers and Tolerance

[3] Gerrie ter Haar, James J. Busuttil, ed. (2005). Bridge or barrier: religion, violence, and visions for peace, Volume 2001. BRILL. p. 125.

[4] “Mirror of the Cruel and Horrible Spanish Tyranny Perpetrated in the Netherlands, by the Tyrant, the Duke of Alba, and Other Commanders of King Philip II”. World Digital Library. 1620. Retrieved 2013-08-25.

[5] “Books associated with Trading Places – the East India Company and Asia 1600-1834, an Exhibition.”.

[6] Campbell, John; Watts, William (1760). “Memoirs of the Revolution in Bengal, Anno Domini 1757”. World Digital Library. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

[7] Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland

Vol. 2, No. 1 (1835), pp. 13-42

[8] Thomas B. Macaulay, “Warren Hastings,” in Essays and Poems, Boston, n.d., 11, 566-67.

Sometimes It’s Hard to Be a Woman

The spinning wheel—few material objects so succinctly represent patriarchal oppression under colonialism. The wheel was once the expedient implement to create thread and yarn, and pondering the vast demand in the 18th century before the industrial revolution rendered it obsolete, to make a capital fortune in cotton required innumerable wheels and an equal representation of labor. However, prior to colonization the indigenous peoples of India and the New World did not have a standard market economy. Their societies had not eclipsed the “hunter-gatherer” way of life that was displaced ages ago in Europe. Their nations did not participate in market trade on a grand scale; capitalism did not exist, nor did the European socio-cultural standards that governed the most developed nations. Arguably, a colonial power’s first goal when establishing new territories is to assimilate the indigenous peoples into the collective, allowing for more taxable subjects and labor to support the Crown and its endeavors. But the power must conten d with established social, cultural, political, economic, and religious infrastructure; to successfully bring a colony into the imperial fold is a difficult endeavor. Entrenched in a clash of cultures is a proxy colonial powers used to bring the Natives under an assimilationist regime: the sexual repression of women. In colonial territories, implementation of traditional European gender roles allowed imperial powers to realign socio-cultural infrastructure and generate a free international market. And this did not occur solely in the cotton trade: regardless of the economic resource the territory provided, the power found labor when men assumed the role of “worker” and women of “domestic.” Through the rising a falling periods of colonization in India and modern day Mexico, the controlling powers—Britain and Spain—sought to repress women to curry further control in their colonies. The ultimate results of their actions remain unclear, but myriad evidence suggests this repression furthered political, social, and cultural hierarchies disadvantaging women; as a direct result, in many edges of empire women still suffer lasting consequences of colonial gender subjugation.

d with established social, cultural, political, economic, and religious infrastructure; to successfully bring a colony into the imperial fold is a difficult endeavor. Entrenched in a clash of cultures is a proxy colonial powers used to bring the Natives under an assimilationist regime: the sexual repression of women. In colonial territories, implementation of traditional European gender roles allowed imperial powers to realign socio-cultural infrastructure and generate a free international market. And this did not occur solely in the cotton trade: regardless of the economic resource the territory provided, the power found labor when men assumed the role of “worker” and women of “domestic.” Through the rising a falling periods of colonization in India and modern day Mexico, the controlling powers—Britain and Spain—sought to repress women to curry further control in their colonies. The ultimate results of their actions remain unclear, but myriad evidence suggests this repression furthered political, social, and cultural hierarchies disadvantaging women; as a direct result, in many edges of empire women still suffer lasting consequences of colonial gender subjugation.

To analyze sexual repression in these Spanish and British colonies, I turn my focus away from print sources and call the reader’s attention to primary photographs. Period photography offers a window through which we can observe the light of history, and allow ourselves the opportunity to step into someone else’s skin and experience their experience. Unlike print resources that rely on imagery to captivate the reader, primary photographs provide the reader with concrete image—an accurate and candid representation of the past.

We begin with the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire and the establishment of New Spain. As a colonial power, Spanish peoples sought the riches buried in their new territory; however, mining was a costly and dangerous expense. Of course the silver would be well worth the incursion when extracted—recognizing this hard reality, the Spanish colonists plunged headfirst into a program to assimilate and subjugate the Native peoples to do the Crown’s work. Although this was not slavery, it was certainly a form of indentured servitude. In return for Spanish “protection,” the Indian people would work Spanish land in an agreement called encomienda. This compact formed the beginnings of gender oppression in the New World; as Catholics, the Spanish considered the Indian people inferior, or gente sin razon: a people without reason. The missions considered it their duty to baptize and convert as many of the pagan Natives as possible. Whereas the Crown traded in silver, the Faith traded in souls. But despite an ocean’s breadth the Spanish would apply their socio-cultural gender construction to the indigenous. Man worked to the Spaniard’s content, lest he be beaten or his family starved and uprooted from their home; woman would fall under the watchful eye of the missionaries. Culture clash was inevitable, but nothing disturbed the Spanish missionaries more than the Indian’s unchaste sexual conduct. Prior to Colonialism, female fertility and sexuality had been celebrated in Native tradition and heritage. Nevertheless, missionaries concurred that in order to foster Indian conversion to Catholicism, they would supplant Native gender roles with a Spanish gender hierarchy. Culturally and religiously, Indian women’s “cosmic power” emanates from fertility.[i] The Spanish missionaries sought to realign women’s role by “enforcing monogamous sexual relations,” and “suppressing rituals, symbols, and religious societies associated with fertility and sexuality.”[ii] The missionaries considered female sexuality alien, women’s bodies “base and vile;” thus, the reconstruction of gender roles was based on morality, and a woman’s fertility was the single “most important source of her value.”[iii]

As the tendrils of Spanish colonial influence snaked across the continent, missionaries established residence among tribal communities; these infamous Alto missions in present day California provide evidence suggesting that these Natives suffered among the most abhorrent conditions in the entirety of Spanish colonial rule. All women below marriage age were required to take residence in the mission, in a “dormitory” called monjeríos. In truth, “dormitory” is an ineffectual description of what a monjerío really was: a tool to subjugate female sexuality, under the closest scrutiny. These were cages for young Indian women, preventing them from any contact with the men in their tribe. Deviant sexual conduct—or any deviant conduct for that matter—was severely punished; the corma would chain a woman’s legs together so she could not separate them.[iv] Those women who suffered miscarriages were “punished by ‘shaving the head, flogging for fifteen subsequent days, [wearing] iron on the feet for three months, and having to appear every Sunday in church, on the steps leading up to the altar, with a hideous painted wooden child… in her arms’ representing the dead infant;” the missionaries considered all miscarriages acts of infanticide.[v]

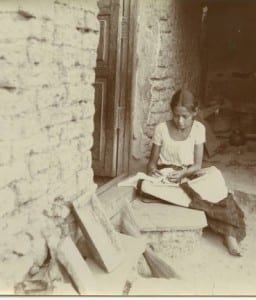

From an early age in monjeríos girls are taught to sew, cook, spin cotton, and accomplish similar “household tasks.”[vi] We can observe this process in action in [Girl sewing on doorstep] (http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/mex/id/664/rec/2) by Winfield Scott. There is no way of knowing whether this picture was taken in a monjerío, but she provides a very accur ate depiction of what a monjerío girl might look like. She is working diligently, and does not appear to notice the camera. However, as the rest of the photographs in Scott’s collection are blocked, we can rationally assume that she was blocked as well. The difference between analyzing a candid photograph and a blocked photograph is that the latter is more subjective according to the opinions and views of the photographer. Scott chose an excellent setting for his photograph: the girl’s surroundings are decrepit. With the exception of what appears to be a running tap behind her, there are no commodities to speak of. Women in monjeríos were rarely allowed outside the mission buildings, and were certainly never allowed outside the compound. This photograph demonstrates exactly the living conditions one might expect to see in a monjerio; bereft of all but essential furniture, and without luxuries of any kind, the Spartan design of these quarters served to break women of immoral, “uncontrolled sexuality and confused gender roles.”[vii]

ate depiction of what a monjerío girl might look like. She is working diligently, and does not appear to notice the camera. However, as the rest of the photographs in Scott’s collection are blocked, we can rationally assume that she was blocked as well. The difference between analyzing a candid photograph and a blocked photograph is that the latter is more subjective according to the opinions and views of the photographer. Scott chose an excellent setting for his photograph: the girl’s surroundings are decrepit. With the exception of what appears to be a running tap behind her, there are no commodities to speak of. Women in monjeríos were rarely allowed outside the mission buildings, and were certainly never allowed outside the compound. This photograph demonstrates exactly the living conditions one might expect to see in a monjerio; bereft of all but essential furniture, and without luxuries of any kind, the Spartan design of these quarters served to break women of immoral, “uncontrolled sexuality and confused gender roles.”[vii]

That the patriarchy held ultimate control of Indian women’s sexuality is apparent in several more period photographs, also taken by Scott. These pictures, [Girl by river] (http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/mex/id/670/rec/8) and Lily (http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/mex/id/663/rec/1), are both disturbing in that they are intentionally blocked to engender feelings of sexual objectification. The girl by the river and Lily are blocked in remarkably similar poses; their legs are casually crossed as they sit ; their arms support their upper body in a way that appears naturally resilient. As this photograph is blocked, that the girl by the river’s cleavage shows is no accident, but a deliberate staging conducted by Scott. Furthermore, as if in irony, Lily is holding a white rose in her hand; she holds the bloom towards us, as if offering it. White roses have long been known as a symbol of purity; this distinction in mind, we begin to understand the purpose of these photographs. Both the girl and Lily stare directly into the camera. As a viewer, the first time I saw these photographs together I was taken aback by the maturity evident in their expressions. It is not hard to tell these girls are both young—they appear to be roughly thirteen years old—and yet they look as if they have endured experiences that hardened their resolve. The patriarchy has compromised their sexuality to such an extent that these young girls are prepared to give themselves to a stranger. Unfortunately, this might have been their fate. When establishing missions, the Spanish would organize a garrison to protect the Faith; considering that Indians vastly outnumbered both missionaries and soldiers, in regards to the duality of the Spanish assimilation program outlined by the Faith and enforced by the Crown these far away missions were essentially state actors. The garrison’s presence has tremendous significance: soldiers committed appalling crimes against Indian women, including rape and murder; fami

; their arms support their upper body in a way that appears naturally resilient. As this photograph is blocked, that the girl by the river’s cleavage shows is no accident, but a deliberate staging conducted by Scott. Furthermore, as if in irony, Lily is holding a white rose in her hand; she holds the bloom towards us, as if offering it. White roses have long been known as a symbol of purity; this distinction in mind, we begin to understand the purpose of these photographs. Both the girl and Lily stare directly into the camera. As a viewer, the first time I saw these photographs together I was taken aback by the maturity evident in their expressions. It is not hard to tell these girls are both young—they appear to be roughly thirteen years old—and yet they look as if they have endured experiences that hardened their resolve. The patriarchy has compromised their sexuality to such an extent that these young girls are prepared to give themselves to a stranger. Unfortunately, this might have been their fate. When establishing missions, the Spanish would organize a garrison to protect the Faith; considering that Indians vastly outnumbered both missionaries and soldiers, in regards to the duality of the Spanish assimilation program outlined by the Faith and enforced by the Crown these far away missions were essentially state actors. The garrison’s presence has tremendous significance: soldiers committed appalling crimes against Indian women, including rape and murder; fami lies would commit their daughters to monjeríos so as to protect them from the “unbridled lust” of the soldiers.[viii] In fact, the existence of monjeríos was justified in part by the Faith’s interest in protecting the Indian women’s chastity.[ix] The girls seem to regard the photographer—Scott—with some modicum of dissatisfaction. Presumably, if these pictures were taken in a monjerío the girls would know to avoid the interest of men, especially strange men, for fear of retribution by the missionaries or assault by a soldier. But they must both know that marriage lies in wait for them when a suitable Catholic groom comes calling to the mission. This would perhaps in part explain the sewing girl’s (above) disinterest with the man photographing her. Once married in a Catholic ceremony, the women would be allowed to return to their husband’s house under his private sphere of patriarchy. Until then, they lived through a unique hell. The Spanish missions accomplished their gender restructuring with remarkable gusto. In employing forced assimilation to Indian culture, they were granted with souls to save and men to work.[x] affixing women’s sexuality in the patriarchy’s pocket was the last piece of the puzzle.

lies would commit their daughters to monjeríos so as to protect them from the “unbridled lust” of the soldiers.[viii] In fact, the existence of monjeríos was justified in part by the Faith’s interest in protecting the Indian women’s chastity.[ix] The girls seem to regard the photographer—Scott—with some modicum of dissatisfaction. Presumably, if these pictures were taken in a monjerío the girls would know to avoid the interest of men, especially strange men, for fear of retribution by the missionaries or assault by a soldier. But they must both know that marriage lies in wait for them when a suitable Catholic groom comes calling to the mission. This would perhaps in part explain the sewing girl’s (above) disinterest with the man photographing her. Once married in a Catholic ceremony, the women would be allowed to return to their husband’s house under his private sphere of patriarchy. Until then, they lived through a unique hell. The Spanish missions accomplished their gender restructuring with remarkable gusto. In employing forced assimilation to Indian culture, they were granted with souls to save and men to work.[x] affixing women’s sexuality in the patriarchy’s pocket was the last piece of the puzzle.

Now, we turn our attention to gender subjugation in India. The similarities between British and Spanish colonial gender subjugation are evident. In India socio-cultural treatment of women already held the gender to be subservient to men; we must recognize a very fine distinction for how the British applied this means of colonial control. The British sought revenues through the establishment of trade in India and the control of cotton textile exports. Creating beautiful cottons textiles—the kind British popular culture craved—remains to this day a process rooted in tradition and heritage.[xi] Interestingly, the British did not seek to enforce gender subjugation directly, but they certainly allowed the Indian Brahmins to perpetuate it. In developing new law, the British “defined a structure of revenue-collection and settlement that depended preeminently on local bonds of social cohesion based on patrilineal descent… British colonial officials idealized ‘the timeless village’… where the folk who accepted and supported the [British] Raj lived in ‘grateful peace.’”[xii] The British controlled sexuality through passive means. Utilizing the existing caste system to redefine legal obligations as colonial power, India’s laws were defined by local custom, for which the British instituted the necessary infrastructure.[xiii] It was certainly a subtle means of achieving colonial domination, quite different from those Spain used.

But it is critical to understand that British colonization tactics were identical to the Spanish in certain capacities, such as public perception of the Indian people. Just as the Spanish considered Indians—especially female Indians—immoral for embracing sexuality, Elie cites “the harem syndrome” as the colloquial perception of Indian women as suffering under the yoke of Islam.[xiv] From the outside looking in, the British had an inadequate understanding of what harem represented as a tradition, and thus the word’s meaning rapidly evolved into something scandalous. This concept is reinforced by Ghosh’s theories concerning the effects of colonization on the colonial woman. She claims that the common law disadvantaging British women derived from prior cultural and societal standards; namely, that women are inferior to men—they constitute the “weaker sex.”[xv] Ghosh and Elie’s theories juxtapose British and Indian women on the sexual level. The  harem syndrome contributes to British perception of Indian women as sexually “unbridled,” whereas the British woman was “demure,” and “sexually restrained.”[xvi] To understand this concept is to understand how Britain established its international trade system in India. The British simply had to structure a gendered distinction between “work” and “leisure;” men contributed to the furtherance of colonization by working on public service projects, primarily railroads. Women participated in what the British defined as the “leisurely” activity of producing textiles.[xvii] This naturalization technique served to provide the labor necessary to produce Indian infrastructure on a massive scale, and simultaneously furthered revenues from the production and sale of cotton.

harem syndrome contributes to British perception of Indian women as sexually “unbridled,” whereas the British woman was “demure,” and “sexually restrained.”[xvi] To understand this concept is to understand how Britain established its international trade system in India. The British simply had to structure a gendered distinction between “work” and “leisure;” men contributed to the furtherance of colonization by working on public service projects, primarily railroads. Women participated in what the British defined as the “leisurely” activity of producing textiles.[xvii] This naturalization technique served to provide the labor necessary to produce Indian infrastructure on a massive scale, and simultaneously furthered revenues from the production and sale of cotton.

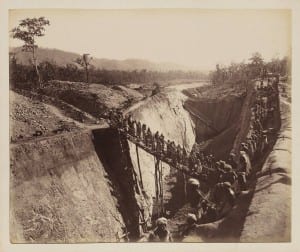

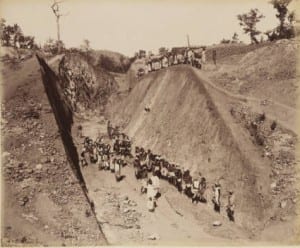

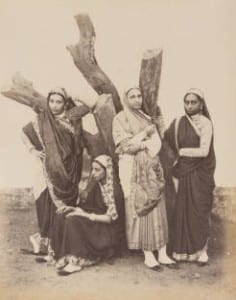

Pictured above is [Bengal-Nagpur Railway Construction, Photograph No. 14] (http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/eaa/id/1478/rec/13). This is just one snippet of the complex network of railroads produced during British colonial rule. The large number of men working in this picture serves to corroborate the gendered work distinction. This is a candid shot, meaning that the photographer did not block any of his subject matter. Its significance is its contribution to positive public perception of Britain’s activities in India. British viewers saw the occupation of India was contributing positively to the economy, and providing jobs for those who might otherwise be unemployed. The photograph demonstrates the relentless march from Indian antiquity to modern industry. Further, it reinforced the familiar notion of man as the laborer and woman as the domestic. This is at least partially reflected in William Johnson’s Parsee Ladies (http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/eaa/id/670/rec/39). The women in this picture are obviously blocked, and the same details that painted a repressive picture for Mexican Indians in Lily etc. are present here. These women are dressed relatively well in juxtaposition to the poorer Indian castes; however, this is irrelevant in analyzing each of the four wo men’s distinct mannerisms. The woman on the left is posed in an equally provocative position as in [Girl by river]. Note the position of her arms and legs: as opposed to her company, she cocks her right arm against her hip and the left behind her head, an elbow resting on a stump. You can almost see something of what one might loosely dub “American sex appeal.” But the woman on the center left is flatly disregarding Johnston, taking up an insignificant space below the level of her companions. Her expression is apathetic, in that she has no expression; her face is completely blank. The woman on the right gapes at the camera, but not with malice or surprise. There is something haunting in her gaze, something hollow, like an empty promise. The final woman leans casually against the tree trunk, and her expression seems to represent polite indifference, like the Mona Lisa smile. Whether Johnston intended this interesting juxtaposition is unclear. What is clear is that at least two of the four women are unhappy with something—perhaps, the injurious nature of British colonialism. The woman on the left happily perpetuates the notion of Indian women as sexually rampant. The second and third women represent two sects of Indian opposition to colonial oppression: the woman on the right is haunted by experience, and the crouching woman wants nothing more than to relinquish Johnston’s company as soon as possible. What they have in common is a mutual dislike of the colonial powers, or at least white men in general. After careful analysis, the final woman appears to be folding her arms across her chest as if to cloak herself from the patriarchal gaze of the British people; she is not concerned to share the company of the white man, but she respects her position of subservience. To be sure, the four expressions highlight tremendous confusion. The women live under patriarchal law, but perhaps some question why they should be treated any differently than British colonial women? The oppressed never deserve to be the object of oppression—they seek change. However, at a cursory glance the elements of harem syndrome are the most apparent. I assume that this was Johnston’s goal when blocking this photograph: to perpetuate designations of Indian and corresponding castes for the people of Britain to better understand the nature of the Indian people. What he did not anticipate were the subtle clues his subjects left us with.

men’s distinct mannerisms. The woman on the left is posed in an equally provocative position as in [Girl by river]. Note the position of her arms and legs: as opposed to her company, she cocks her right arm against her hip and the left behind her head, an elbow resting on a stump. You can almost see something of what one might loosely dub “American sex appeal.” But the woman on the center left is flatly disregarding Johnston, taking up an insignificant space below the level of her companions. Her expression is apathetic, in that she has no expression; her face is completely blank. The woman on the right gapes at the camera, but not with malice or surprise. There is something haunting in her gaze, something hollow, like an empty promise. The final woman leans casually against the tree trunk, and her expression seems to represent polite indifference, like the Mona Lisa smile. Whether Johnston intended this interesting juxtaposition is unclear. What is clear is that at least two of the four women are unhappy with something—perhaps, the injurious nature of British colonialism. The woman on the left happily perpetuates the notion of Indian women as sexually rampant. The second and third women represent two sects of Indian opposition to colonial oppression: the woman on the right is haunted by experience, and the crouching woman wants nothing more than to relinquish Johnston’s company as soon as possible. What they have in common is a mutual dislike of the colonial powers, or at least white men in general. After careful analysis, the final woman appears to be folding her arms across her chest as if to cloak herself from the patriarchal gaze of the British people; she is not concerned to share the company of the white man, but she respects her position of subservience. To be sure, the four expressions highlight tremendous confusion. The women live under patriarchal law, but perhaps some question why they should be treated any differently than British colonial women? The oppressed never deserve to be the object of oppression—they seek change. However, at a cursory glance the elements of harem syndrome are the most apparent. I assume that this was Johnston’s goal when blocking this photograph: to perpetuate designations of Indian and corresponding castes for the people of Britain to better understand the nature of the Indian people. What he did not anticipate were the subtle clues his subjects left us with.

It is no mean feat to break the yoke of colonial gender oppression. Perhaps the most important aspect of this analysis is to understand that to an extent only the oppressed can break their bonds; although there may be entities from the outside looking in that see oppression for what it is, only those who have suffered invidious discrimination know the strength to break free of it.[xviii] The spinning wheel of colonialism and sexual subjugation is cyclical. A colonial power does not acquire territories to leave them untouched. Imperial powers will always seek to effect broad and sweeping change to achieve their interests. But change is cyclical as well. The Industrial Revolution made the spinning wheel obsolete; now, as democratic institutions span the world over, equality is slowly but surely rendering gender repression as useless as the wheel that once symbolized it.

_______________________________________________________________

Notes

[i] Pauline Turner Strong, “Feminist Theory and the ‘Invasion of the Heart’ in North America,” Ethnohistory 43, no. 4 (Autumn 1996): 683-712, JSTOR (689).

[ii] Ibid., 689.

[iii] Antonia I. Castañeda, “Engendering the History of Alta California 1769-1848: Gender, Sexuality, and the Family,” California History 76, no. 2/3 (Summer – Fall 1997): 230-59, EBSCOhost (231).

[iv] Terria Smith, “Under Lock and Key,” News from Native California 28, no. 2 (2015),

[v] Ibid., 235.

[vi] Chelsea K. Vaughn, “Locating Absence: The Forgotten Presence of Monjeríos in Alta

California Missions,” Southern California Quarterly 93, no. 2 (Summer 2011): 141-74, JSTOR (170).

[vii] Strong, 695

[viii] Smith

[ix] Smith; Castañeda.

[x] Castañeda, 235

[xi] Michelle Maskiell, “Embroidering the Past: Phulkari Textiles and Gendered Work as ‘Tradition’ and ‘Heritage’ in Colonial and Contemporary Punjab,” The Journal of Asian Studies 58, no. 2 (May 1999): 361-88, JSTOR (361).

[xii] Ibid., 363.

[xiii] Ibid., 363.

[xiv] Serge D. Elie, “The Harem Syndrome: Moving Beyond Anthropology’s Discursive

Colonization of Gender in the Middle East,” Alternatives: Local, Global, Political 29, no. 2 (March-May 2004): 139-69, JSTOR (140).

[xv] Durba Ghosh, “Gender and Colonialism: Expansion or Marginalization?” The Historical

Journal 47, no. 3 (September 2004): 737-55, JSTOR (738).

[xvi] Ibid., 740.

[xvii] Maskiell, 362.

[xviii] John R. Chavez, “Aliens in Their Native Lands: The Persistence of Internal Colonial

Theory,” Journal of World History 22, no. 4 (December 2011): 758-809, JSTOR (801-2).

_______________________________________________________________

Bibliography

- Anne M. Price. “Colonial History, Muslim Presence, and Gender Equity Ideology: A Cross-National Analysis.” International Journal of Sociology 38, no. 1 (Spring 2008): 81-103. JSTOR.

- Antonia I. Castañeda. “Engendering the History of Alta California 1769-1848: Gender, Sexuality, and the Family.” California History 76, no. 2/3 (Summer – Fall 1997): 230-59. EBSCOhost.

- Chelsea K. Vaughn. “Locating Absence: The Forgotten Presence of Monjeríos in Alta California Missions,” Southern California Quarterly 93, no. 2 (Summer 2011): 141-74. JSTOR.

- Durba Ghosh. “Gender and Colonialism: Expansion or Marginalization?” The Historical Journal 47, no. 3 (September 2004): 737-55. JSTOR.

- John R. Chavez. “Aliens in Their Native Lands: The Persistence of Internal Colonial Theory.” Journal of World History 22, no. 4 (December 2011): 758-809. JSTOR.

- Leslie C. Gates. “The Strategic Uses of Gender in Household Negotiations: Women Workers on Mexico’s Northern Border.” Bulletin of Latin American Research 21, no. 4 (October 2002): 507-26. JSTOR.

- Leti Volpp. “Feminism versus Multiculturalism.” Columbia Law Review 101, no. 5 (June 2001): 1181-1218. JSTOR

- Michelle Maskiell. “Embroidering the Past: Phulkari Textiles and Gendered Work as ‘Tradition’ and ‘Heritage’ in Colonial and Contemporary Punjab.” The Journal of Asian Studies 58, no. 2 (May 1999): 361-88. JSTOR.

- Pauline Turner Strong. “Feminist Theory and the ‘Invasion of the Heart’ in North America.” Ethnohistory 43, no. 4 (Autumn 1996): 683-712. JSTOR.

- Serge D. Elie. “The Harem Syndrome: Moving Beyond Anthropology’s Discursive Colonization of Gender in the Middle East.” Alternatives: Local, Global, Political 29, no. 2 (March-May 2004): 139-69. JSTOR.

- Terria Smith. “Under Lock and Key.” News from Native California 28, no. 2 (2015). http://web.b.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=e98a93f1-f445-4fd0-8dfe-d8276940983b%40sessionmgr114&vid=5&hid=102

Social Class Hierarchy and Labor Oppression in Late 19th Century India and Mexico

The Indian Nationalist movement and the Mexican revolution both came about due to rapid economic development and the subsequent mistreatment of the poor labor force. Yet, in both cases, the wealthy elite were the ones who gained the most from these uprisings. The late 19th century marked the beginning of industrialization in Mexico and India, with economic expansion being the focal point for leaders at the time. In India, the British raj used Indian elites to gain support across the country. As a result, a caste system was formed, dividing India and its native population. Indian merchants and the religious intellectuals known as Brahmin were classified as elites in this newly created system, while the lower castes were made up of nomadic tribes and Shudras laborers. This lower, working class was created as a means for Britain to capitalize off of India’s abundance of economic wealth. Inevitably, the underpayment of these laborers along with the horrendous working conditions they were placed in helped ignite change and a move towards independence. Around the same time, Porfirio Diaz took control in Mexico with his elitist agenda set on economic restructuring, with the help of foreign investment, and political stability through social repression. This socioeconomic reform favored the rich and further divided Mexico, alienating landless peasants. Nonetheless, much like how the Indian elites first challenged the British raj, a wealthy landowner by the name of Francisco Madero was the first to question Diaz’s oppressive rule. Madero made himself out to be a representative of the working class with his political and agrarian reform. By pressuring Diaz, he gained the support of the working class and peasants throughout Mexico. Nationalism in India and the Mexican revolution were both pioneered by their elite, wealthy classes, however, without the abuse of the working class and each ruler’s overzealous need for economic power neither would have gained much ground.

The Industrial Revolution gave rise to new industrial centers in India. With this, came the need for infrastructure expansion throughout the country. British rulers promoted the construction of railways in order to further their markets for trade in India and overseas. With an extensive system of railroads, they saw the opportunity to not only restructure India’s economy, but also reinvent its’ traditional society. Daniel Thorner gives an example of how British leaders perceived the railway system as a way to westernize India’s indigenous culture in his article, The Pattern of Railway Development in India. He uses a quote from 1848 which says, “This is a matter of extreme importance in India, where the energy of individual thought has long been cramped by submission to despotic governments, to irresponsible and venal subordinates, to ceremonies and priesthood of a highly irrational religion, and to a public opinion found not on investigation, but on traditional usages and observances” (Thorner 203). Britain hoped to gain economic control and induce cultural change throughout India with this expansion. As fear of social unrest grew among British officials, they saw the railway as an opportunity to gain political and military control of the colony. In doing so, they created a religious and financial hierarchy that further subjugated the Indian working class.

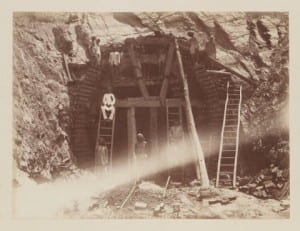

Photograph number 43 of the construction of the Bengal-Nagpur railway portrays this hierarchy among Indian workers. The British divided their workforce based upon wealth and oftentimes even religious beliefs. Hindu elite and merchants were given safer, better paying positions, overseeing the work of the lower castes. This is apparent in the photo, as only two of the workers are fully clothed, appear well kempt, and distinctively standout due to their unblemished, clean-cut uniform. Whereas, the remaining workers are covered in dirt, some even shirtless and barefoot. Even though Europeans and high class Indians were greatly outnumbered, they were treated better and received much higher pay than the tribal and low caste citizens who were shipped in from across the country to work on the railroads.

The favoritism shown by the British towards the higher castes in Indian society can be partially attributed to the fact that Indian businessmen played a founding role in the creation of the railway system. Particularly in Bengal, one of the emerging Industrial centers, merchants realized the value of these railroads and the profit they could make by utilizing them. Thorner mentions one of these significant entrepreneurs in his article. The Bengali merchant, Dwarkanath Tagore, was reported to have offered to raise one-third of the capital required to construct a railway connecting the northwest city of Calcutta to a wealth of coalfields above Burdwan (Thorner 202). Though this was an isolated case, it still expresses the interests and optimism that most upper class Indians shared. Many believed that while the British may profit from this venture, they too had something to gain from an interconnected economic system. However, as Thorner points out, “They walked in the shadows of the vigorous British merchants and railway promoters. The conception, promotion, and launching of India’s railways were all British” (Thorner 202). Indian merchants, no matter the wealth or intelligence, could not compete with the British businesses that flocked to India to benefit from its abundance in resources. This disadvantage, that all Indians faced, ultimately led to the creation of the Indian National Congress and other working class political movements. Predominantly Hindu elite, the Indian National Congress focused on equality rather than independence by critiquing the English economic policy in India. In spite of this, it still helped awaken the nationalist movement and gave laborers hope and a better life that they could strive towards.

An unintended consequence for the British, the railways successfully connected the whole country for the first time and laid out the foundation for nationalism by uniting Indians from all over the country. Before the construction, British officials were able to keep conflicts and uprisings isolated in there respective areas. Whereas afterwards, information traveled fast across the country and isolated strikes turned into countrywide protests. Workers began demanding higher wages and their hazardous working conditions were documented and shared throughout India. Photograph number 16 of the Bengal-Nagpur Railway construction shows the dangers most of these laborers faced. The haphazardly constructed bridges and trenches give the impression that British officials were careless and held little value for the lives of the native people. This is also seen through what little clothes the workers could provide for themselves. Like the previous photograph, many appear half-dressed and without shoes, representative of their quality of life and what little compensation they received for their hard work. Women and children can even be seen in the photograph, working alongside their families in a desperate effort to earn enough to support themselves and their loved ones. As this ill treatment spread across India and became well known, more and more labor groups stood up against the British raj. Nitin Sinha reports in her article, The World of Workers’ Politics: Some Issues of Railway Workers in Colonial India, that strikes erupted across the country as workers demanded wage increases, in some cases as high as 75 percent (Sinha 1007). These labor strikes united the working class and solidified their nationalist interests along with their growing desire for independence. These rebellions were then used by Indian elites as a means to coax their way into positions of power in the Indian government and, in the end, force the British out of their country.

Like India, Mexico faced social oppression in the face of a cruel leader who sought to restructure the economic and political system purely as a benefit for himself and the Mexican elite. Porfirio Diaz used the production of mines, railroads, and agriculture to increase foreign investments and raise the wealth of the few elite individuals who controlled these businesses. He further alienated the poor and middle class citizens by selling ejidos to these wealthy businessmen and foreign investors. These ejidos or haciendas were plots of communal land used for agriculture. As the wealthy took advantage of this expansion under Diaz, the distribution of ejidos lead to a serious problem of landlessness among the impoverished people. As a result, lower class Mexicans were forced to lease land from these wealthy, in some cases foreign, businesses. However, the government was also required to approve the leasing of ejidos, which furthered the corruption and social standings of the elite. Ejidatarios, the name given to those who rented plots, did not actually own or have any rights to the land they paid for. In many cases, peasants were left landless and, as farmers, they had no way of providing for themselves or their families. Often times these peasants were forced to seek work as laborers on these haciendas and were further oppressed by the authority of the wealthy landowners. David Walker highlights this exploitation in his article, Homegrown Revolution: The Hacienda Santa Catalina del Alamo y Anexas and Agrarian Protest in Eastern Durango, Mexico, 1897-1913. He takes note of the fact that, “Hacienda managers increased productivity by reducing wages, eliminating surplus employees, charging higher rents to tenants, extracting maximum advantage from sharecroppers, and enclosing hacienda land and collecting fees from local residents for the use of water, wood, pastures, and other resources” (Walker 241). These changes, brought about as a way to increase profitability among wealth hacienda owners and government officials, further lengthened the economic gap between the upper and lower classes. Predictably, these restrictions on laborers led to widespread animosity towards Porfirio Diaz and the hacienda owners.

As frustration built, Francisco Madero saw an opportunity to overthrow Diaz’s dictatorship and reinvent Mexican society. He proposed a plan called the Plan de San Luis Potosi, which called for an end of Diaz’s regime along with a redistribution of land and rule by the Mexican working class. However, unlike the landless peasants that were rising up alongside him, Madero was born into wealth and owned land across Mexico.

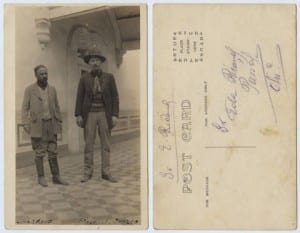

It can clearly be seen in the photograph titled Madero and Pascual Orozco, that Madero, along with the man beside him, are well dressed and neatly groomed. Also, they appear to be standing in front of a rather large, lavish house. This further perpetuates the idea that Mexican peasants had no voice in politics or social reform at the time and change didn’t come about until the rich, elite stepped in to carry the torch. Indian laborers paralleled this struggle as their protests went unheard until the Hindu elite organized movements against the British rule. However, while Indian elites wanted independence and created a sense of nationalism across India, Madero sought political power and used the oppression of landless Mexicans as a means to further his own self-interests.

In contrast with the Indian nationalist movement, the lower class society in Mexico took up arms against the upper class in their fight for equality. Instead of a countrywide nationalist movement, it seemed to only spread among those who were poverty stricken and those economically trapped by the abusive power of the hacienda owners. As a result, uprisings began in rural areas and were usually orchestrated by the peasants that were opposed to the rules dictated by their hacienda owners. Keith Haynes explains in his article, Dependency, Post imperialism, and the Mexican Revolution: An Historiographic Review, that the Mexican elites were often times the target of lower class attacks. He adds, “Where anarchists were well-organized and influential, their call to ‘abolish capitalism and government’ revealed the preeminence of class motives” (Haynes 246). The country was split, with peasants rising up against the rich, Mexican landowners and foreign investors that were given land by the government.

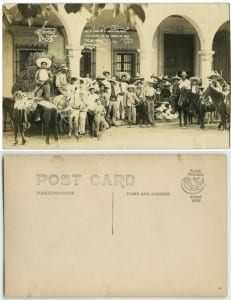

The photograph of the Execution in Mexico shows this socioeconomic divide. The two young men being hung appear to be of a lower class because of their dirty, disheveled clothes. The hacienda setting makes out the well-dressed men over watching the execution to be hacienda owners or perhaps foreign investors, as the two men in the background are much lighter skinned than the others. This photograph provides further evidence for the plight of the lower class and expresses the tension amongst social classes in Mexico during the revolution. In the end, Mexican property owners are forced to play their hand. Haynes describes the landowners reasoning for entering into the revolution as an attempt to rescue Mexican capitalism from peasant and working class assaults (Haynes 246). In Mexico, the wealthy landowners moved against the landless peasants, trumping their agrarian revolutionary movement, and ultimately creating a new revolution with their own agenda. Whereas in India, the elite and working class joined together to force the British into action and established their nationalist ideals nationwide.

Although both movements came about as a result of social class disorder that led to the abuse of the poor, working class and a universal distrust of political leaders. The Mexican Revolution and the nationalist movement in India ended with much different results. While India established unity against the tyrannical colonial power of Great Britain, Mexican revolutionaries had conflicting outlooks for the future of their country. This rift in socioeconomic class prolonged the revolution and worsened Mexico’s political and economic standing in ways that the country has yet to recover from.

Work Cited

Execution in Mexico. 1910-1917. DeGolyer Library, Dallas. SMU Central University Libraries. Web.

Haynes, Keith A. “Dependency, Postimperialism, and the Mexican Revolution: An Historiographic Review.” Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos 7.2 (1991): 225-51.

Sinha, Nitin. “The World of Workers’ Politics: Some Issues of Railway Workers in Colonial India, 1918–1922.” Modern Asian Studies 42.05 (2008): 999-1033.

Thorner, Daniel. “The Pattern of Railway Development in India.” The Far Eastern Quarterly 14.2 (1955): 201-16.

Walker, David W. “Homegrown Revolution: The Hacienda Santa Catalina del Alamo y Anexas and Agrarian Protest in Eastern Durango, Mexico, 1897-1913.” The Hispanic American Historical Review. 72.2 (1992): 239-273.

The Everyday: How Everyday Photographs can Connect Distinct Cultures

Photographing the everyday? Why do that? Most people don’t have an everyday life that others really want to see. Fortunately, some photographers have documented the everyday life of various cultures throughout history, which allows us to draw insightful connections between vastly different societies. The similarities between Mexico and India are few and far between; they are 9,000 miles apart, on different continents, with different cultural and religious traditions. Despite the obvious differences between the cultures, photographs of the everyday in both countries demonstrate similarities that tie the two cultures together. These historical photographs allow us to examine rural and urban lifestyles of the cultures, drawing parallels and noticing differences between various social classes of the different cultures. Additionally, everyday photographs provide detailed visual evidence of labor conditions in the work force, demonstrating the nature of everyday jobs in both cultures. Photographs provide perspective on parent/child relationships that show the different roles each play within the family of different cultures. As many people in early cultures were illiterate, photographing the everyday allows us to recount history from the ground up because it provides us with a perspective that traditional texts cannot and details history that would otherwise go undocumented. Through an examination of everyday photographs, we are able to draw interesting conclusions about labor, family life, culture and poverty in rural and urban spaces in both India and Mexico.

While rural life may not always be glamorous, it provides a true perspective on the rich cultural and religious traditions that connect India and Mexico. Although the importance of rural life is often overshadowed by booming urban centers, rural societies provide legitimate cultural and economic value to both India and Mexico. For example, urban centers were glorified and rural life was grossly overlooked in Indian culture until the arrival of Gandhi, perhaps the most recognizable religious figure of the 20th century. The Indian nationalist movement was a largely urban phenomenon, not reaching into the plethora of rural societies “until Gandhi arrived on the scene and turned it upside down1.” Gandhi viewed rural life as a valid reflection of “the essence of Indian Civilization” and he understood rural India as the real India because it did not conform to outside pressures, like many of the large urban centers. Similarly, the importance of rural Mexican culture is obvious, as historian Nathan Whetten claims, “Mexican rural life is, in effect, an examination of what today is most representative of Mexican culture and society2.” Similar to India, rural Mexico had rich cultures that ultimately were instrumental in shaping the country’s history by demonstrating true, uninfluenced traditions. Additionally, Gandhi’s infatuation with rural society provided a deep, peaceful religious sentiment to rural India, as Gandhi preached Hinduism and nonviolent religious practices to the cultures he visited. Likewise, rural migrants in Mexico retained a worldview that was “largely centered on the work ethic and proscriptions of costly worldly behavior” due to their deeply catholic roots3. The religious practices united both India and Mexico and shaped the rural societies, as they instilled peace in India and allowed the Mexicans to live a more efficient and informed religious life. The rich cultural history and deep religious sentiment in rural societies in India and Mexico provided great value to the development of the true personality of the nations and demonstrates similarities in seemingly differing cultures.