The Indian Nationalist movement and the Mexican revolution both came about due to rapid economic development and the subsequent mistreatment of the poor labor force. Yet, in both cases, the wealthy elite were the ones who gained the most from these uprisings. The late 19th century marked the beginning of industrialization in Mexico and India, with economic expansion being the focal point for leaders at the time. In India, the British raj used Indian elites to gain support across the country. As a result, a caste system was formed, dividing India and its native population. Indian merchants and the religious intellectuals known as Brahmin were classified as elites in this newly created system, while the lower castes were made up of nomadic tribes and Shudras laborers. This lower, working class was created as a means for Britain to capitalize off of India’s abundance of economic wealth. Inevitably, the underpayment of these laborers along with the horrendous working conditions they were placed in helped ignite change and a move towards independence. Around the same time, Porfirio Diaz took control in Mexico with his elitist agenda set on economic restructuring, with the help of foreign investment, and political stability through social repression. This socioeconomic reform favored the rich and further divided Mexico, alienating landless peasants. Nonetheless, much like how the Indian elites first challenged the British raj, a wealthy landowner by the name of Francisco Madero was the first to question Diaz’s oppressive rule. Madero made himself out to be a representative of the working class with his political and agrarian reform. By pressuring Diaz, he gained the support of the working class and peasants throughout Mexico. Nationalism in India and the Mexican revolution were both pioneered by their elite, wealthy classes, however, without the abuse of the working class and each ruler’s overzealous need for economic power neither would have gained much ground.

The Industrial Revolution gave rise to new industrial centers in India. With this, came the need for infrastructure expansion throughout the country. British rulers promoted the construction of railways in order to further their markets for trade in India and overseas. With an extensive system of railroads, they saw the opportunity to not only restructure India’s economy, but also reinvent its’ traditional society. Daniel Thorner gives an example of how British leaders perceived the railway system as a way to westernize India’s indigenous culture in his article, The Pattern of Railway Development in India. He uses a quote from 1848 which says, “This is a matter of extreme importance in India, where the energy of individual thought has long been cramped by submission to despotic governments, to irresponsible and venal subordinates, to ceremonies and priesthood of a highly irrational religion, and to a public opinion found not on investigation, but on traditional usages and observances” (Thorner 203). Britain hoped to gain economic control and induce cultural change throughout India with this expansion. As fear of social unrest grew among British officials, they saw the railway as an opportunity to gain political and military control of the colony. In doing so, they created a religious and financial hierarchy that further subjugated the Indian working class.

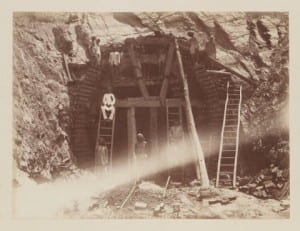

Photograph number 43 of the construction of the Bengal-Nagpur railway portrays this hierarchy among Indian workers. The British divided their workforce based upon wealth and oftentimes even religious beliefs. Hindu elite and merchants were given safer, better paying positions, overseeing the work of the lower castes. This is apparent in the photo, as only two of the workers are fully clothed, appear well kempt, and distinctively standout due to their unblemished, clean-cut uniform. Whereas, the remaining workers are covered in dirt, some even shirtless and barefoot. Even though Europeans and high class Indians were greatly outnumbered, they were treated better and received much higher pay than the tribal and low caste citizens who were shipped in from across the country to work on the railroads.

The favoritism shown by the British towards the higher castes in Indian society can be partially attributed to the fact that Indian businessmen played a founding role in the creation of the railway system. Particularly in Bengal, one of the emerging Industrial centers, merchants realized the value of these railroads and the profit they could make by utilizing them. Thorner mentions one of these significant entrepreneurs in his article. The Bengali merchant, Dwarkanath Tagore, was reported to have offered to raise one-third of the capital required to construct a railway connecting the northwest city of Calcutta to a wealth of coalfields above Burdwan (Thorner 202). Though this was an isolated case, it still expresses the interests and optimism that most upper class Indians shared. Many believed that while the British may profit from this venture, they too had something to gain from an interconnected economic system. However, as Thorner points out, “They walked in the shadows of the vigorous British merchants and railway promoters. The conception, promotion, and launching of India’s railways were all British” (Thorner 202). Indian merchants, no matter the wealth or intelligence, could not compete with the British businesses that flocked to India to benefit from its abundance in resources. This disadvantage, that all Indians faced, ultimately led to the creation of the Indian National Congress and other working class political movements. Predominantly Hindu elite, the Indian National Congress focused on equality rather than independence by critiquing the English economic policy in India. In spite of this, it still helped awaken the nationalist movement and gave laborers hope and a better life that they could strive towards.

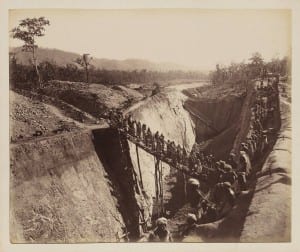

An unintended consequence for the British, the railways successfully connected the whole country for the first time and laid out the foundation for nationalism by uniting Indians from all over the country. Before the construction, British officials were able to keep conflicts and uprisings isolated in there respective areas. Whereas afterwards, information traveled fast across the country and isolated strikes turned into countrywide protests. Workers began demanding higher wages and their hazardous working conditions were documented and shared throughout India. Photograph number 16 of the Bengal-Nagpur Railway construction shows the dangers most of these laborers faced. The haphazardly constructed bridges and trenches give the impression that British officials were careless and held little value for the lives of the native people. This is also seen through what little clothes the workers could provide for themselves. Like the previous photograph, many appear half-dressed and without shoes, representative of their quality of life and what little compensation they received for their hard work. Women and children can even be seen in the photograph, working alongside their families in a desperate effort to earn enough to support themselves and their loved ones. As this ill treatment spread across India and became well known, more and more labor groups stood up against the British raj. Nitin Sinha reports in her article, The World of Workers’ Politics: Some Issues of Railway Workers in Colonial India, that strikes erupted across the country as workers demanded wage increases, in some cases as high as 75 percent (Sinha 1007). These labor strikes united the working class and solidified their nationalist interests along with their growing desire for independence. These rebellions were then used by Indian elites as a means to coax their way into positions of power in the Indian government and, in the end, force the British out of their country.

Like India, Mexico faced social oppression in the face of a cruel leader who sought to restructure the economic and political system purely as a benefit for himself and the Mexican elite. Porfirio Diaz used the production of mines, railroads, and agriculture to increase foreign investments and raise the wealth of the few elite individuals who controlled these businesses. He further alienated the poor and middle class citizens by selling ejidos to these wealthy businessmen and foreign investors. These ejidos or haciendas were plots of communal land used for agriculture. As the wealthy took advantage of this expansion under Diaz, the distribution of ejidos lead to a serious problem of landlessness among the impoverished people. As a result, lower class Mexicans were forced to lease land from these wealthy, in some cases foreign, businesses. However, the government was also required to approve the leasing of ejidos, which furthered the corruption and social standings of the elite. Ejidatarios, the name given to those who rented plots, did not actually own or have any rights to the land they paid for. In many cases, peasants were left landless and, as farmers, they had no way of providing for themselves or their families. Often times these peasants were forced to seek work as laborers on these haciendas and were further oppressed by the authority of the wealthy landowners. David Walker highlights this exploitation in his article, Homegrown Revolution: The Hacienda Santa Catalina del Alamo y Anexas and Agrarian Protest in Eastern Durango, Mexico, 1897-1913. He takes note of the fact that, “Hacienda managers increased productivity by reducing wages, eliminating surplus employees, charging higher rents to tenants, extracting maximum advantage from sharecroppers, and enclosing hacienda land and collecting fees from local residents for the use of water, wood, pastures, and other resources” (Walker 241). These changes, brought about as a way to increase profitability among wealth hacienda owners and government officials, further lengthened the economic gap between the upper and lower classes. Predictably, these restrictions on laborers led to widespread animosity towards Porfirio Diaz and the hacienda owners.

As frustration built, Francisco Madero saw an opportunity to overthrow Diaz’s dictatorship and reinvent Mexican society. He proposed a plan called the Plan de San Luis Potosi, which called for an end of Diaz’s regime along with a redistribution of land and rule by the Mexican working class. However, unlike the landless peasants that were rising up alongside him, Madero was born into wealth and owned land across Mexico.

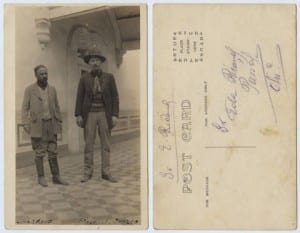

It can clearly be seen in the photograph titled Madero and Pascual Orozco, that Madero, along with the man beside him, are well dressed and neatly groomed. Also, they appear to be standing in front of a rather large, lavish house. This further perpetuates the idea that Mexican peasants had no voice in politics or social reform at the time and change didn’t come about until the rich, elite stepped in to carry the torch. Indian laborers paralleled this struggle as their protests went unheard until the Hindu elite organized movements against the British rule. However, while Indian elites wanted independence and created a sense of nationalism across India, Madero sought political power and used the oppression of landless Mexicans as a means to further his own self-interests.

In contrast with the Indian nationalist movement, the lower class society in Mexico took up arms against the upper class in their fight for equality. Instead of a countrywide nationalist movement, it seemed to only spread among those who were poverty stricken and those economically trapped by the abusive power of the hacienda owners. As a result, uprisings began in rural areas and were usually orchestrated by the peasants that were opposed to the rules dictated by their hacienda owners. Keith Haynes explains in his article, Dependency, Post imperialism, and the Mexican Revolution: An Historiographic Review, that the Mexican elites were often times the target of lower class attacks. He adds, “Where anarchists were well-organized and influential, their call to ‘abolish capitalism and government’ revealed the preeminence of class motives” (Haynes 246). The country was split, with peasants rising up against the rich, Mexican landowners and foreign investors that were given land by the government.

The photograph of the Execution in Mexico shows this socioeconomic divide. The two young men being hung appear to be of a lower class because of their dirty, disheveled clothes. The hacienda setting makes out the well-dressed men over watching the execution to be hacienda owners or perhaps foreign investors, as the two men in the background are much lighter skinned than the others. This photograph provides further evidence for the plight of the lower class and expresses the tension amongst social classes in Mexico during the revolution. In the end, Mexican property owners are forced to play their hand. Haynes describes the landowners reasoning for entering into the revolution as an attempt to rescue Mexican capitalism from peasant and working class assaults (Haynes 246). In Mexico, the wealthy landowners moved against the landless peasants, trumping their agrarian revolutionary movement, and ultimately creating a new revolution with their own agenda. Whereas in India, the elite and working class joined together to force the British into action and established their nationalist ideals nationwide.

Although both movements came about as a result of social class disorder that led to the abuse of the poor, working class and a universal distrust of political leaders. The Mexican Revolution and the nationalist movement in India ended with much different results. While India established unity against the tyrannical colonial power of Great Britain, Mexican revolutionaries had conflicting outlooks for the future of their country. This rift in socioeconomic class prolonged the revolution and worsened Mexico’s political and economic standing in ways that the country has yet to recover from.

Work Cited

Execution in Mexico. 1910-1917. DeGolyer Library, Dallas. SMU Central University Libraries. Web.

Haynes, Keith A. “Dependency, Postimperialism, and the Mexican Revolution: An Historiographic Review.” Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos 7.2 (1991): 225-51.

Sinha, Nitin. “The World of Workers’ Politics: Some Issues of Railway Workers in Colonial India, 1918–1922.” Modern Asian Studies 42.05 (2008): 999-1033.

Thorner, Daniel. “The Pattern of Railway Development in India.” The Far Eastern Quarterly 14.2 (1955): 201-16.

Walker, David W. “Homegrown Revolution: The Hacienda Santa Catalina del Alamo y Anexas and Agrarian Protest in Eastern Durango, Mexico, 1897-1913.” The Hispanic American Historical Review. 72.2 (1992): 239-273.