Photographing the everyday? Why do that? Most people don’t have an everyday life that others really want to see. Fortunately, some photographers have documented the everyday life of various cultures throughout history, which allows us to draw insightful connections between vastly different societies. The similarities between Mexico and India are few and far between; they are 9,000 miles apart, on different continents, with different cultural and religious traditions. Despite the obvious differences between the cultures, photographs of the everyday in both countries demonstrate similarities that tie the two cultures together. These historical photographs allow us to examine rural and urban lifestyles of the cultures, drawing parallels and noticing differences between various social classes of the different cultures. Additionally, everyday photographs provide detailed visual evidence of labor conditions in the work force, demonstrating the nature of everyday jobs in both cultures. Photographs provide perspective on parent/child relationships that show the different roles each play within the family of different cultures. As many people in early cultures were illiterate, photographing the everyday allows us to recount history from the ground up because it provides us with a perspective that traditional texts cannot and details history that would otherwise go undocumented. Through an examination of everyday photographs, we are able to draw interesting conclusions about labor, family life, culture and poverty in rural and urban spaces in both India and Mexico.

While rural life may not always be glamorous, it provides a true perspective on the rich cultural and religious traditions that connect India and Mexico. Although the importance of rural life is often overshadowed by booming urban centers, rural societies provide legitimate cultural and economic value to both India and Mexico. For example, urban centers were glorified and rural life was grossly overlooked in Indian culture until the arrival of Gandhi, perhaps the most recognizable religious figure of the 20th century. The Indian nationalist movement was a largely urban phenomenon, not reaching into the plethora of rural societies “until Gandhi arrived on the scene and turned it upside down1.” Gandhi viewed rural life as a valid reflection of “the essence of Indian Civilization” and he understood rural India as the real India because it did not conform to outside pressures, like many of the large urban centers. Similarly, the importance of rural Mexican culture is obvious, as historian Nathan Whetten claims, “Mexican rural life is, in effect, an examination of what today is most representative of Mexican culture and society2.” Similar to India, rural Mexico had rich cultures that ultimately were instrumental in shaping the country’s history by demonstrating true, uninfluenced traditions. Additionally, Gandhi’s infatuation with rural society provided a deep, peaceful religious sentiment to rural India, as Gandhi preached Hinduism and nonviolent religious practices to the cultures he visited. Likewise, rural migrants in Mexico retained a worldview that was “largely centered on the work ethic and proscriptions of costly worldly behavior” due to their deeply catholic roots3. The religious practices united both India and Mexico and shaped the rural societies, as they instilled peace in India and allowed the Mexicans to live a more efficient and informed religious life. The rich cultural history and deep religious sentiment in rural societies in India and Mexico provided great value to the development of the true personality of the nations and demonstrates similarities in seemingly differing cultures.

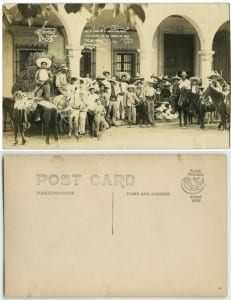

Photographing the everyday urban life in India and Mexico provides a clear idea of the large gap between social classes and the role that urban life played in the development of Indian and Mexican societies. Because they are highly concentrated areas of the countries, studying trends in the urban population offers a true understanding of life in the areas that supposedly drove the nations. For example, En la Casa de D. Juan Valadez portrays a group men standing with guns and horses outside of a well-developed urban building. We can infer that these men associated with the middle/lower class because their clothing suggests that they are troops in the Mexican revolution. Although the urban societies conducted the majority of the country’s important business, it is notable that there is a significant gap between social classes in urban areas. Mexican cultures utilized a “Sistema de Castas,” which grouped demographics by blood purity and deemed societal value based off of heritage. Similarly, Indian urban centers employed a despicable caste system that encouraged tremendous gaps between social classes and caused a rift in urban societies. Due to the similarity and monotony of rural life, discrepancies in social classes were not prominent in rural living, but urban societies encouraged one to identify with a social class and to behave accordingly. Though commonly rural life was overshadowed by urban societies, British imperialists took an opposite approach and overlooked the urban centers in India, viewing it as a largely rural nation. On the other hand, Mexican urban centers “have grown at faster rates than the country as a whole… in large part from differential internal migration4.” While Indian urban centers were overlooked by imperialists, Mexican urban centers flourished, as Mexicans flocked to urban areas to find jobs and support for their families. Although different in the way urban areas were viewed, Mexico and India employ similar caste systems in urban centers that encouraged steep gaps between the upper and lower classes, which connected the two developing societies.

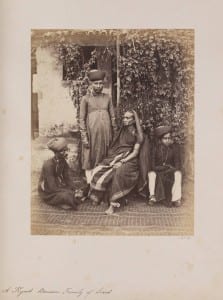

Photographing everyday family life offers a clear indication of how Mexican and Indian societies approached familial relations, allowing us to discover trends in families of different social classes and showing the importance of one’s birth family. Photographs of Indian and Mexican families allow for a deeper understanding of the roles of a child versus an adult within families in societies in different hemispheres. From an outside view it may appear that family life in India and Mexico are quite different, but there is one strong connection that makes them surprisingly similar. The photograph, Mexican family around a table, depicts a family in modest clothing in a downtrodden, open-air home conversing, while a young boy holds his infant sibling in the background. By the condition of their home and the clothing they are wearing, we can infer that this is a lower class family, in which every family member is expected to contribute to everyday operations. While the adults work hard to provide bare necessities for the family, the children are likely expected to contribute to maintain the household, as we notice a young boy caring for his younger sibling. On the other hand, one will notice an Indian family simply sitting outside their average home wearing respectable clothing in A Kyast Banian Family of Surat. This image supports a relaxed tone and allows the audience to deduce that this is a middle class family, in which the adults are expected to support the family while the children enjoy a more relaxed upbringing. While these two photographs depict different lifestyles in different regions of the world, in both regions one’s social class, childhood, and profession are largely dependent upon the family to which you were born. Historian Henry Thompson discusses the advantages one is offered if they are born into a high-class family in India: an abundance of wealth, a good education, and significant societal respect5. Similarly, one’s quality of life in Mexican culture depends heavily on their familial situation; the likelihood of escaping the social class that one was born into is low and children are expected to be serious contributors to the family in low-class families. Although photographs of every day family life in India and Mexico are significantly different, familial relations in the cultures are linked by the commonality that the social class of the family likely determines one’s lifestyle for the duration of their life.

The far-reaching, borderless nature of poverty is inevitably evident through photographing the everyday life of citizens of India and Mexico, connecting the nations’ impoverished through nearly identical circumstances. Not only a global issue today, poverty was even more apparent in the development of India and Mexico, due to the heavy emphasis each society placed on strict social classes. In the image Pets of the Family, one notices a seemingly impoverished, rural family, sitting outside of their makeshift home with their animals, which are probably their most valuable resources for production. The children, dressed in unimpressive clothing, appear to be responsible for the animals and the whole family looks skinny and exhausted. Pets of the family paints a valid picture of an impoverished family in which all members work, yet still struggle to provide food for each other. Unfortunately, many farmers and servants in the rural areas of Mexico were not able to make a viable living, subjecting their families to poverty and unsafe living conditions. Likewise, nutritionist and historian Tara Gopaldas writes about the gross deficit of proteins, calories and vitamins in Indian children, suggesting that poverty affected almost 75% of some rural Indian communities6. Although poverty certainly existed in urban areas, rural communities were the most commonly effected demographic, as they were commonly occupied by servants who were not respected in society and received astonish low wages. Everyday photographs of the impoverished enable us to connect the demographics of rural poverty in India and Mexico, and further prove that poverty has been (and will be) a far-reaching cultural issue.

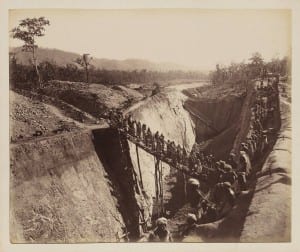

As labor conditions and the treatment of the working class varies widely across societies, photographing the everyday worker allows us to draw parallels between working conditions in India and Mexico. Noticing how various societies treat the working class enables us to discover the countries’ treatment of the middle class and the governments’ support of the working class. In the late 19th century, railways were the gateway to commerce; they were the most efficient way to transport bulk material and connect many geographical regions. Not surprisingly, much labor was needed to construct them. In photograph 16 from the Bengal-Napur Railway Construction collection, hundreds of workers appear to be performing arduous tasks in an arid, rural atmosphere, while unsafely positioned on the edge of a cliff. As this image suggests, the government had little regard and no policies in place to establish safe conditions for the working class Indians. Additionally, the noticeable gap between the wealthy and the working class is especially evident through photograph 16, as the wealthy lived a lavish lifestyle in the urban areas while the working class performed demanding manual labor in perilous conditions. Likewise, the popularity of the railroad was rapidly increasing in Mexico, but it provided a significant conflict of interest to the rural people, as it displaced many from their homes but provided them with a minimalƒ source of income7. Further mistreatment of the Native Americans is evident as Historian Teresa Van Hoy notes that “the railroad occupied 31 properties without proper compensation,” causing tremendous financial grievances for the local people8. Because the working class was not protected by the government and was forced into imperfect conditions, the characteristics of the labor force in India and Mexico proved to be strikingly similar. Photographs of everyday labor demonstrated that Mexico and India were united by workers performing for unfairly low wages and under conditions that were far from ideal in rural areas.

As cultures that appear to be wildly different in all aspects from geographic location to tendencies in the workforce, India and Mexico share a surprising plethora of characteristics in each country’s development. From noticing trends in urban versus rural life to the shared, unfortunate poverty, photographs of the everyday lives of citizens of India and Mexico allow us to draw surprising parallels between the distinct nations. As opposed to simply studying textual accounts of these nations’ history, a survey of photographs allows use to have a more true grasp of the everyday lives of citizens, as photographs convey vivid details that critical texts cannot. Although urban centers undoubtedly played a pertinent role in Mexican and Indian history, these photographs in rural settings document the lives of unreached people and allow us to connect labor conditions, poverty, and family life in Mexico and India. As many working and lower class citizens were illiterate, photographing the everyday gives us a holistic approach that documents the experiences of all peoples and gives a voice to the voiceless.

Endnotes

- Surinder S. Jodhka, “Nation and Village: Images of Rural India in Gandhi, Nehru and Ambedkar,” Economic and Political Weekly 37, no. 32 (August 2002): 3343-53.

- Norman D. Humphrey, “Review,” American Journal of Sociology 55, no. 1 (July 1949): 115-16.

- “Pentecostal Adaptations in Rural and Urban Mexico: An Anthropological Assessment,”Mexican Studies, 2004.

- Robert G. Burnight, Nathan L. Whetten, and Bruce D. Waxman, “Differential Rural-Urban Fertility in Mexico,” American Sociological Review 21, no. 1 (February 1956): 3-8.

- Henry O. Thompson, “Review,” International Journal for World Peace 5, no. 1 (1998): 96-99.

- Tara Gopaldas, “Hidden Hunger: The Problem and Possible Interventions,”Economic and Political Weekly 41, no. 34 (August/September 2006): 3671-74.

- Teresa M. Van Hoy, “La Marcha Violenta? Railroads and Land in 19th-Century Mexico,”Bulletin of Latin American Research 19, no. 1 (January 2000): 33-61.

- Van Hoy, “La Marcha Violenta? Railroads,” 33-61

Bibliography

Burnight, Robert G., Nathan L. Whetten, and Bruce D. Waxman. “Differential Rural-Urban Fertility in Mexico.” American Sociological Review 21, no. 1 (February 1956): 3-8. Accessed April 25, 2015. http://www.jstor.org.proxy.libraries.smu.edu/stable/2089332?Search=yes&resultItemClick=true&searchText=urban&searchText=mexico&searchText=in&searchText=1900&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicSearch%3FQuery%3Durban%2Bmexico%2Bin%2B1900%26amp%3Bprq%3Durban%2Bmexico%26amp%3Bgroup%3Dnone%26amp%3Bfc%3Doff%26amp%3Bso%3Drel%26amp%3Bacc%3Don%26amp%3Bhp%3D25%26amp%3Bwc%3Don&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents.

Gopaldas, Tara. “Hidden Hunger: The Problem and Possible Interventions.” Economic and Political Weekly 41, no. 34 (August/September 2006): 3671-74. Accessed April 26, 2015. http://www.jstor.org.proxy.libraries.smu.edu/stable/4418615?Search=yes&resultItemClick=true&searchText=rural&searchText=india&searchText=AND&searchText=children&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicSearch%3FQuery%3Drural%2Bindia%2BAND%2Bchildren%26amp%3Bacc%3Don%26amp%3Bwc%3Don%26amp%3Bfc%3Doff%26amp%3Bgroup%3Dnone&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents.

Humphrey, Norman D. “Review.” American Journal of Sociology 55, no. 1 (July 1949): 115-16. Accessed April 25, 2015. http://www.jstor.org.proxy.libraries.smu.edu/stable/2770407?Search=yes&resultItemClick=true&searchText=rural&searchText=mexico&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicSearch%3FQuery%3Drural%2Bmexico%26amp%3Bprq%3Drural%2Bindia%26amp%3Bgroup%3Dnone%26amp%3Bacc%3Don%26amp%3Bhp%3D25%26amp%3Bso%3Drel%26amp%3Bwc%3Don%26amp%3Bfc%3Doff&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents.

Jodhka, Surinder S. “Nation and Village: Images of Rural India in Gandhi, Nehru and Ambedkar.” Economic and Political Weekly 37, no. 32 (August 2002): 3343-53. Accessed April 26, 2015. http://www.jstor.org.proxy.libraries.smu.edu/stable/4412466?Search=yes&resultItemClick=true&searchText=Rural&searchText=india&searchText=AND&searchText=Gandhi&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicSearch%3FQuery%3DRural%2Bindia%2BAND%2BGandhi%26amp%3Bacc%3Don%26amp%3Bwc%3Don%26amp%3Bfc%3Doff%26amp%3Bgroup%3Dnone&seq=3#page_scan_tab_contents.

“Pentecostal Adaptations in Rural and Urban Mexico: An Anthropological Assessment.” Mexican Studies, 2004. Accessed April 26, 2015. http://www.jstor.org.proxy.libraries.smu.edu/stable/10.1525/msem.2004.20.1.145?Search=yes&resultItemClick=true&searchText=rural&searchText=mexico&searchText=AND&searchText=religion&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicSearch%3FQuery%3Drural%2Bmexico%2BAND%2Breligion%26amp%3Bacc%3Don%26amp%3Bwc%3Don%26amp%3Bfc%3Doff%26amp%3Bgroup%3Dnone.

Thompson, Henry O. “Review.” International Journal for World Peace 5, no. 1 (1998): 96-99. Accessed April 27, 2015. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20751212?Search=yes&resultItemClick=true&searchText=family&searchText=AND&searchText=19th&searchText=century&searchText=india&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicSearch%3FQuery%3Dfamily%2BAND%2B19th%2Bcentury%2Bindia%26amp%3Bacc%3Don%26amp%3Bwc%3Don%26amp%3Bfc%3Doff%26amp%3Bgroup%3Dnone&seq=2#page_scan_tab_contents.

Van Hoy, Teresa M. “La Marcha Violenta? Railroads and Land in 19th-Century Mexico.” Bulletin of Latin American Research 19, no. 1 (January 2000): 33-61. Accessed April 28, 2015. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3339704?Search=yes&resultItemClick=true&searchText=mexico&searchText=in&searchText=19th&searchText=century&searchText=AND&searchText=labor&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicSearch%3FQuery%3Dmexico%2Bin%2B19th%2Bcentury%2BAND%2Blabor%26amp%3Bprq%3Dmexico%2Bin%2B19th%2Bcentury%2BAND%2Bwork%26amp%3Bgroup%3Dnone%26amp%3Bhp%3D25%26amp%3Bacc%3Don%26amp%3Bfc%3Doff%26amp%3Bso%3Drel%26amp%3Bwc%3Don&seq=6#page_scan_tab_contents.