[iframe id=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/-9VcwqcXxn8″]

The Women of India and Mexico: Economy and Caste

This class has shed light on the fact that the two very different countries of India and Mexico have many similarities. From initial colonization, to castes systems, to revolutions, and more, studying India and Mexico in one class has made many connections never before thought possible from two countries on opposite sides of the planet. Although lectures and readings are important to make these connections, visual aids such as historical photographs are important to gather knowledge of these two empires. The people of these countries, especially the women, can be analyzed through photographs because “though undoubtedly a tool of perception, behind each photograph there is ‘not only a private eye, but layers of history as well’. In the process, as one views the photographs, one is also introduced to changing photographic techniques, women as ethnographic types, the importance of the studio and of backdrop, [and] the vibrancy of ‘action’ shots…” (Karlekar xi). Through visual analysis of historical photographs, the lives of working women in Mexico and India can be captured and examined. Aspects of these women’s lives include their job, caste system, and economic status.

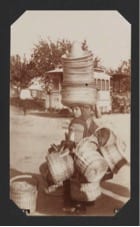

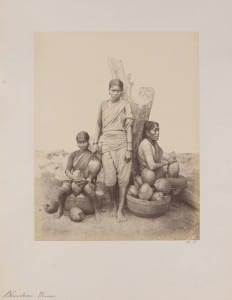

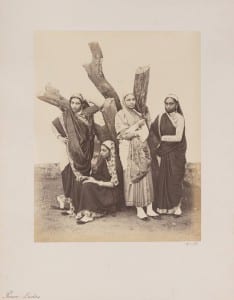

One theory about the origin of the caste system in India dates back to the beginning of class society and settled agriculture, and has existed ever since that time. A very important feature of the caste system is its control over women’s labor, for “caste not only determines social division of labour but also sexual division of labour. Certain tasks have to be performed by women while certain other tasks are meant for men. In agriculture for instance, women can engage themselves in water-regulation, transplanting, weeding, but not ploughing” (Desai 33). If not working in agriculture, women would work from the household, known as family-labor. The Indian women made a living from spinning and weaving, to milking cattle and selling butter, to marketing fruits and vegetables, like the women in the photograph below with their coconuts. They most likely make their living off of this produce, although it is evident that these women do not have high paying jobs. The level of dirtiness of their clothes and the simplicity of their clothes, which allowed for more physical mobility to produce manual labor, is evidence of their lower economic status. Absence of shoes also proves the inability of the women to belong to a higher caste. These Indian women are also very thin, demonstrating that they do not have an excess of money for food. Their caste does not allow them to have a more sufficient job to make more of a living. On the surface level, their jobs appear to be diverse, but when more research is conducted into the caste system, it can be seen that the job possibilities for women were in fact the opposite. Overall, subordination of women was justified by the caste system and divisions of labor.

do not have high paying jobs. The level of dirtiness of their clothes and the simplicity of their clothes, which allowed for more physical mobility to produce manual labor, is evidence of their lower economic status. Absence of shoes also proves the inability of the women to belong to a higher caste. These Indian women are also very thin, demonstrating that they do not have an excess of money for food. Their caste does not allow them to have a more sufficient job to make more of a living. On the surface level, their jobs appear to be diverse, but when more research is conducted into the caste system, it can be seen that the job possibilities for women were in fact the opposite. Overall, subordination of women was justified by the caste system and divisions of labor.

In modern day, the way one dresses is important. The emphasis on appearance was just as present in the early nineteenth century. As stated by Karlekar, “Dressing for the occasion was often important as clothes and other accoutrements were vital props in the spectacle of presenting oneself for an audience” (xiv). With the use of photography for showcasing oneself on the rise, outfits for these photoshoots were crucial to those at the time. The Parsi gara or garo, a sari with Chinese embroidery in white or a variety of colored threads, was introduced to India in the latter part of the nineteenth century. Brought back to the country by Parsi traders in the 1850s, the colorfully embroidered borders of butterflies and peonies soon became a popular style and spread throughout India and, “by the latter part of the nineteenth century, the Parsi gara or garo became increasingly popular among the westernized elite of the Bombay and Bengal Presidencies” (Karlekar xiv). Although one general style prevailed at the time, women took initiative in changing the dress slightly based on location. Women on the west coast and northern India draped the sari pallav over their right shoulder, while women in Bengal started to drape the cloth over the left shoulder. Therefore, it can be seen and deduced that the women in the photo are from either the west coast or northern part of India because of the way they drape the sari. These women also complete the dress of western elite females by wearing closed shoes and ornamenting themselves with one earring, while the other ear is firmly placed behind the mathubanu, or head binding over the sari pallav. Although the spread of the Parsi gara or garo expanded to women across the nation, it is apparent that these women are of a higher caste. The four women pictured have enough wealth to have the beautiful and detailed gara or garo, closed shoes, and jewelry, including bangles, earrings, and rings, proving that they do not complete manual labor to survive. Related, it is important to note the visible health of these women, as it looks as though they have enough nutritious food to eat. The caste of these women provides a higher quality of life for them, and perhaps it can be deduced that the women in the photograph do not need to work at all because of their caste. The economic status, caste, and job, or lack thereof, of these women is seen in the photograph alone.

These women also complete the dress of western elite females by wearing closed shoes and ornamenting themselves with one earring, while the other ear is firmly placed behind the mathubanu, or head binding over the sari pallav. Although the spread of the Parsi gara or garo expanded to women across the nation, it is apparent that these women are of a higher caste. The four women pictured have enough wealth to have the beautiful and detailed gara or garo, closed shoes, and jewelry, including bangles, earrings, and rings, proving that they do not complete manual labor to survive. Related, it is important to note the visible health of these women, as it looks as though they have enough nutritious food to eat. The caste of these women provides a higher quality of life for them, and perhaps it can be deduced that the women in the photograph do not need to work at all because of their caste. The economic status, caste, and job, or lack thereof, of these women is seen in the photograph alone.

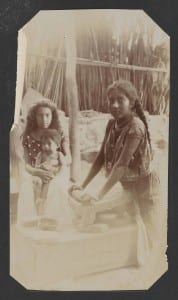

During this same time on the other side of the world, life in Mexico was difficult for all, but more so for women. During and after the Mexican revolution of 1910-1920, Mexicans immigrated to the United States in search of better opportunities. The chaos from the revolution, along with intense poverty in most of the country, motivated Mexicans to make the move. Their dreams included earning enough money to support themselves and their families to provide improved qualities of life. Location was important for them, therefore, “they chose the Southwest because it was accessible; because, having once been part of Mexico, it would be more like home, and because they hoped to fit in easily in a society which already had a large Mexican-American element” (Samora 132). However, most Mexicans knew little besides farming, unaided by their low levels of education. The skilled farmers quickly filled the available jobs in agriculture that paid them low wages, similar to the system in Mexico that they were trying to escape. Many Mexicans lacked money and ranchers were vulnerable to market downturns and unstable weather, so in response, “some sold out to pay taxes while other ranchers subdivided their land among heirs until no parcel remained large enough to support their families” (McKenzie 59). Many Mexican Texans, also known as Tejanos, faced levels of poverty and struggled to feed and clothe their families. But not matter the struggle these people faced, Mexican Texan women continued to serve their traditional foods in this new land, including corn tortillas, tamales, frijoles (beans), chiles, cabrito (kid goat), and nopalitos (cactus leaves).

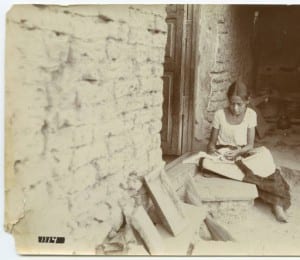

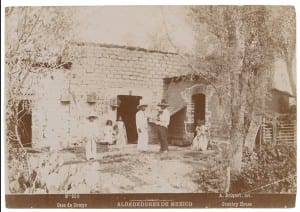

These Mexican Texan families lived in simple houses built of materials gathered from the land. In wetter areas, rain would return the traditional adobe (mud and straw brick) huts into mud. Poor Tejanos lived in “jacales”. A jacal is a hut made from readily available materials to that area, such as mesquite posts. Jacales were built by laying the logs side by side and chinking the spaces in between the boards with mud. These huts would have a peaked roof frame above the walls, thatched with local grasses. Most jacals had packed dirt floors and were vulnerable to insects and bad weather. Most Mexican Texans grew their own food close to their homes, including corn, peppers, beans, tomatoes, and squash. Improving ones quality of life was hard in Mexico and the American Southwest for many reasons, but one profound aspect of life at this time was that, “Some counties prohibited Mexican children from attending school beyond sixth grade” (McKenzie 75). That fact alone means that the children in this photo could already be prohibited from attending school. The poverty that these children live in is evident through their clothing (plain and dirty) and their environment (which appears to be a jacal, with log walls and dirt floors). One of the children is also grinding corn, which is a traditional and cheap food that is easily grown in personal gardens, helping to prove the lower economic status of these children. These children are “working” to help take care of their family, by watching over the younger siblings and preparing food, instead of improving their lives, economic status, and caste by attending school. The disparity of Mexico and the American Southwest previously described is evident in this photo, with females as the main subjects.

The poverty that these children live in is evident through their clothing (plain and dirty) and their environment (which appears to be a jacal, with log walls and dirt floors). One of the children is also grinding corn, which is a traditional and cheap food that is easily grown in personal gardens, helping to prove the lower economic status of these children. These children are “working” to help take care of their family, by watching over the younger siblings and preparing food, instead of improving their lives, economic status, and caste by attending school. The disparity of Mexico and the American Southwest previously described is evident in this photo, with females as the main subjects.

Mexico has many agricultural products in different areas of the country. But one of these products is highly revolved and driven by the female population, and that is coffee. The Mexican state of Veracruz has more coffee workers and grows more coffee than any other state in Mexico. For the last 150 years, the coffee industry created employment for thousands of working Mexican women and fostered development and unionization of a working women’s culture, but, “working women’s culture can be quite distinct from that of working men’s culture” (Fowler-Salamini 10). As the merchants, preparers, and exporters of the product, women had an important role in stimulating the development of Latin American coffee-export economies. Although coffee remained Mexico’s second most important agricultural export for many decades, the country also had other more lucrative exports, including cotton, sugarcane, and minerals, that obtained more attention and importance. The state of Veracruz and its coffee economies were primarily concentrated in five highland towns, being Xalapa, Huatusco, Orizaba, Córdoba, and Coatepec. While studies on the predominantly female labor force of the coffee industry are scarce, the essential and important role of women as coffee sorters, cleaners, and exporters, or escogedoras or desmanchadoras, never went unnoticed. Although working in the coffee industry was linked to manual, low-paying, and less prestigious work, the women themselves never bothered to think of this, as they were able to earn steady seasonal wages and join the public workplace. In the 1920’s, standards of labor in the coffee industry were changing for the better for both men and women. However, “women workers were increasingly marginalized by the men-dominated national trade union movements allied with the officially party that were determined to impose their control over their memberships” (9).

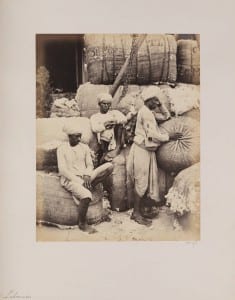

Despite the power the men thought they had, women dominated the coffee sorting aspect of the coffee industry, and created some autonomy in the union and developed leadership positions, not linked to their masculine counterparts. The following photograph was taken in Coatepec in 1904. It shows people sorting coffee, with four out of the six people in the photograph being women. Although these women were considered lower caste citizens because of their profession, they seem healthy, clean, and satisfied that they have a source of income. In addition, through their profession, the Mexican women have a bond and strength in numbers that came solely from the industry. This photograph provides a historical picture of women at their job, improving their economic status, and living through their caste.

Bringing together two very seemingly different cultures can be a difficult task. But the similarities between India and Mexico are more abundant than one would think. Finding these similarities can be accomplished through research in typical textual sources. But visual mediums such as historical photographs are also very useful when learning about people of the past in their empires of the time. Analysis of photographs of working women in both India and Mexico concluded ideas about jobs, different caste systems, and one’s economic status. Throughout history, women have been disrespected and lowered to less desirable standards by men and their societies simply because of their gender. These photographs prove that women worked just as hard as men, if not harder, to make a better life for themselves. No matter the job, or what caste they were in, women always pushed through their struggles. When looking at photographs, or life in general, the saying goes, “beauty is in the eye of the beholder”, and throughout history, women have made it more beautiful.

Bibliography

Desai, Neera, and Maithreyi Krishnaraj. Women and Society in India. Delhi: Ajanta Publications (India), 1987. Print.

Fowler-Salamini, Heather. Working Women, Entrepreneurs, and the Mexican Revolution: The Coffee Culture of Córdoba, Veracruz. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2013. Print.

Karlekar, Malavika. Visualizing Indian Women 1875-1947. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2006. Print.

McKenzie, Phyllis. The Mexican Texans. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2004. Print.

Samora, Julian, and Patricia Vandel Simon. A History of the Mexican American People. Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 1977. Print.

http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/mex/id/2574/rec/3

http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/mex/id/243/rec/87

http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/eaa/id/670/rec/39

http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/eaa/id/747/rec/62

A Socio-Cultural Awakening

What do India and Mexico have in common? On the surface, the similarities are not striking. However, digging deeper into the layers of history reveals a much broader insight into the legacies left behind on these two countries by the colonial-era empires of both Britain and Spain. History books and written primary sources layout a framework for analyzing certain concepts and trends, such as culture, gender, infrastructure, and the military. Photographs, on the other hand, place these concepts in a visual context. They allow us to see the integration of ideas in societies of the past. Historical photographs of India and Mexico exhibit the socio-cultural awakening that took place at the height of nineteenth century European colonialism through depictions of religious and social reform, gender and familial roles, and industrial revolution.

The extensive transformation of social institutions under British colonial rule is one of the many unfaltering themes of India’s history. European expansionism, throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, was fueled by a hunger for land, power, and natural resources, and involved little concern for the welfare of anyone who stood in the way of the growing empires. Europeans entered into already populated regions, such as India and the Americas, and imposed their lifestyles onto civilizations they deemed inferior. The perception of India as a subordinate nation stems from British ideas of the “orient” that shaped how race and gender were recognized and used to assert power over the Indians. These preconceived notions of the native Indian people greatly contributed to the tensions that would later ensue. Sir George Clerk, a nineteenth century administrator, noted: “There are two modes of governing India—with the people, or without the people” (Peers 17). The British had no desire to govern with the people of India, and thus allowed “the social and cultural gap [to remain] wide” (ibid). In order to strengthen their hold, British officials implemented a caste system as a more effective means of organization, rather than directly ruling the Indian people. At this point in time, the caste system was considered “India’s most important social [institution],” along with its “archaic and dominating forms of religious community” (O’Hanlon 100). The interactions between the Caste members and colonial rulers resulted in the establishment of new scribal and commercial elites, and the consolidation of social authority and political power (ibid).

The main caste system, known as the Varna, could be traced back to the original Veda scriptures of the Hindu religion (Stead). The Varna consists of four ranks, starting with Brahmins at the top, following with the Kshatriyas, the Vaishyas, and finally the Shudras. Before British rule, the Varna was simply a method of dividing the traditional Hindu population by social responsibilities. The caste system as we know it today, however, reflects the British appropriation of inherently Hindu systems and practices (Milner). Colonial rulers were quick to capitalize on an existing structure in order to enforce the separation of people by wealth, power, and even occupations. The four Varnas no longer held the same meanings. For example, the Kshatriyas were originally purposed to protect society in times of war, and govern in times of peace (Oon). These people who once held the role of serving humanity, were now expected to engage in mercantile operations in order to fulfill the political and economic demands of the British (ibid). The Lohana people, a subset of the Kshatriyas, are known as members of the urban Hindu mercantile community (Majumdar, 210). Despite the British considering the Kshatriya to be the second highest caste after the Brahmin, their physical appearance does not reflect that. The Lohana men, photographed by William Johnson in 1860, appear to be wearing simple, unadorned cloths that are similar to those of lower-caste Indians, who took on the more labor-intensive jobs such as working in the fields. Even with the deep-rooted Hindu traditions of the Varna, jobs were strictly regulated among the different classes. As the demand for cotton textiles extended throughout the world, the British saw this phenomenon as an opportunity to benefit financially from the Indian economy and its notoriously cheap labor. Both social and economic reformation reached new heights as Britain pushed for sedentarization and industrialization in India concurrently (O’Hanlon, Colonialism and Social Identities in Flux). This campaign by the British transformed what was once a mobile agrarian society, to stationary, and encouraged the development of factories to expand the cotton industry to major cities such as Bombay and Calcutta. The interactions between the Caste members and colonial rulers resulted in the establishment of new scribal and commercial elites, and the consolidation of social authority and political power (O’Hanlon). Industrialization in India, while it was slower than in Europe, sparked more rapid urbanization in the major cities, and the emergence of a new middle class to keep up with the demands of production. In order to meet the needs of their growing empire, the British found it necessary to completely alter social organization, such as converting the Lohanas from warriors to merchants.

The Kshatriya Lohanas are just one of many subgroups whose roles in society were changed by the British reconstruction of the caste system. In fact, when the British Empire abolished slavery in 1833, they lost the manual labor that the slaves once provided (Zgoda). To make up for the shortage of manpower, Colonial rulers made indentured servants out of the lower-caste Indians (ibid). As there were very few opportunities for the uneducated, and now unemployed, Indians to find work, indentured servitude seemed like an ideal job, especially because it provided food and housing (ibid). Many indentured servants later realized the poor quality of life of such a profession, however they were already bound by contract and could not escape the inadequate living conditions. The photograph titled, Ghatee Hamalls, or Bearers, was taken around the 1850s or 1860s by William Johnson, and displays six men outside a building. In the center of the photograph, there is a British man who appears to be lounging in a raised-up compartment, and is talking with a well dressed, middle class Indian man. Four additional Indian men, who are wearing nothing but pieces of cloth, are holding up the compartment. Their actions and lack of suitable clothing suggest that they are of significantly lower class than the other two men. Given that Bearers is the title of the photograph, it is safe to assume that these four men are the bearers, or the male servants, of the wealthy British man that they are tending to. This photograph provides visual insight to the poor working conditions that indentured servants were bound to under the British rule, while also representing two, maybe even three, of the class levels that were prominent in 19th century India.

In the first half of the 19th century, Mexico lacked the people, power, and resources it needed to keep up with the economic and industrial advancements of adjacent nations, and to stand out against their dominating presences. Mexico’s inability to grow left it stuck under the capitalist system, while the United States moved towards industrialization from a more agriculturally based system (Hall). While the United States moved forward with the rest of the world, it almost seemed as if Mexico was moving backward. However, Spain saw Mexico’s challenges as an opportunity for their own economic interests to flourish. It was this intervention by the Spanish that acted as a catalyst in the transformation of the social order within Mexico. The drive for American expansion into the Southwest collided with Mexico’s arising internal conflicts and disruption of social organization. According to Thomas D. Hall, there were several ways “in which Mexican conditions contributed to the 1846 conflict.” He stated that, “globally, there were specific and systematic factors in the Spanish Empire that contributed to… the circumstances of Mexican Independence,” and that “nationally, there were changes in foreign investment, economic development, and the turbulent internal political conditions that lasted from the Hidalgo rebelling in 1810 through the consolidation of power under Porfirio Diaz in 1876” (Hall). Internally, Mexico struggled with a “chaotic government,” that failed to meet the demands of the now industrialized global economy, and cited “transportation costs as one of the two major obstacles to Mexican economic growth in the nineteenth century” (Hall). Mexico’s eventual separation from Spain and newfound economic dependence on Britain led to the introduction of the feudal system, which caused even more instability, especially among the Mexican social classes. Mexico’s complex history and ongoing internal struggles with power and order allowed stronger colonial rulers to assert control over the failing nation.

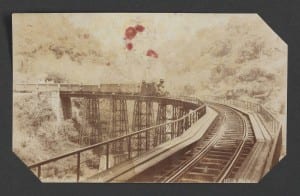

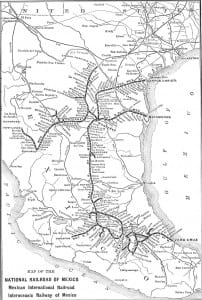

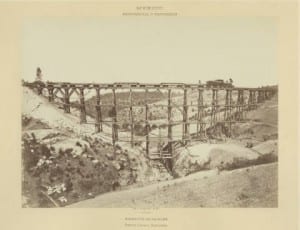

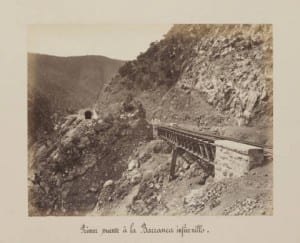

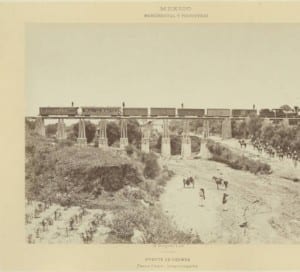

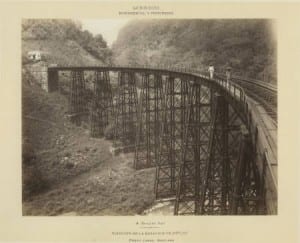

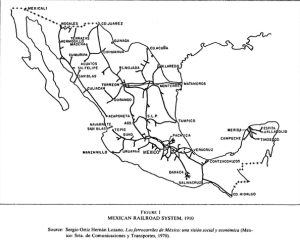

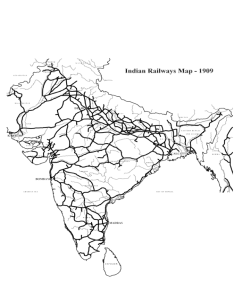

The introduction and expansion of railroad development in the nineteenth century brought about the rapid economic growth that Mexico was looking for (Coatsworth). While the living conditions for the Mexican working class were anything but ideal, the railways greatly impacted the agrarian communities, as well as benefitting the wealthy upper class (Van Hoy). Teresa Van Hoy stated that, “Railroad officials sought to gain access to local resources such as land, water, construction materials, labor, customer patronage, and political favors. Residents, in turn, maneuvered to maximize their gains from the wages, contracts, free passes, surplus materials, and services (including piped water) controlled by the railroad. Those areas of Mexico suffering poverty and isolation attracted public investment and infrastructure” (Van Hoy, Preface). The photographs of the Metlac Bridge and Locomotive on Mexican-Vera Cruz Ry, taken by C.B. Waite in 1902 mark a great triumph in Mexico’s eventual move towards industrialization. As Van Hoy presented in her book, A Social History of Mexico’s Railroads: Peons, Prisoners, and Priests, and as seen on the map of Mexico’s railway system, trains connected people from all over the country, and enhanced the spread of goods and ideas.

Without photographs, we are forced to rely on written and verbal accounts of the past that have been transferred from person to person, and often altered along the way. Yes, it is absolutely possible that many of these historical photographs were staged even in the earliest days of photography; however, historians are obligated to consult many different mediums when conveying the most accurate truth about the past. Looking at history through different lenses opens the floor to alternative perspectives, ideas, and conversations about civilizations before us. The historical photographs of India and Mexico provide us with unique visual insight to the impact of European expansionism and colonialism on the nineteenth century world.

Works Cited and Referenced

Alonso, Ana Mari. Thread of Blood: Colonialism, Revolution, and Gender on Mexico‘s Northern Frontier. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press, 1995.

Andrabi, Tahir and Michael Kuehlwein. “Railways and Price Convergence in British India.” The Journal of Economic History Vol. 70 (2010): 351-377.

Bogart, Dan. “Nationalizations and the Development of Transport Systems: Cross-Country Evidence from Railroad Networks, 1860–1912.where da white wimmin at” The Journal of Economic History. Vol. 69, No.1 (Mar., 2009), pp. 202-237.

Coatsworth, John. “Indispensable Railroads in a Backward Economy: The Case of Mexico.” JSTOR. December 1, 1979

Cuellar, A. B. “Railroad Problems of Mexico.” Annals of The American Academy of Political and Social Science 187 (1936): 193-206. doi:10.1177/000271623618700128

Stead, Estelle. The Caste System in India: The Review of Reviews (1918): 423

Ficker, Sandra Kuntz. “The Export Boom of the Mexican Revolution: Characteristics and Contributing Factors.” JSTOR. Cambridge University Press, Web. 07 Apr. 2015.

Gauss, Susan. “Made in Mexico: Regions, Nation, and the State in the Rise of Mexican Industrialism, 1920s-1940.” The Hispanic American Historical Review Vol. 92 (2012): 574-575.

Glick, Edward B. “The Tehuantepec Railroad: Mexico’s White Elephant”. Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 22, No. 4 (1953): pp. 373-382. JStor.org (accessed April 07, 2015).

Tinker, A New System of Slavery: The Export of Indian Labour Overseas 1820-1920, Oxford University Press, London, 1974

Hall, Thomas D. The Sources of the American Conquest of the Southwest. 167-181.

Hardy, Osgood. “The Revolution and the Railroads of Mexico”. Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 3, No. 3 (Sep., 1934): pp. 249-269. JStor.org (accessed April 07, 2015).

Majumdar, Maya. Encyclopaedia of Gender Equality Through Women Empowerment. New Delhi: Sarup & Sons, 2005. Print.

Milner, Murray, Jr. “Hindu Eschatology and the Indian Caste System: An Example of Structural Reversal.” Journal of Asian Studies 52, no. 2 (May 1993): 298-319. Accessed April 7, 2015.

O’Hanlon, Rosalind. A Comparison Between Women and Men: Tarabai Shinde and the critique of gender relations in colonial India. Madras: Oxford University Press, 1994.

O’Hanlon, Rosalind. Colonialism and Social Identities in Flux: Class, Caste, and Religious Community. Peers and Gooptu. Oxford University Press, 2012.

Oonk, Gijsbert. “The Changing Culture of the Hindu Lohana Community.” Contemporary South Asia. Carfax, 1 Mar. 2004. Web. <http://www.sikh-heritage.co.uk/heritage/sikhhert EAfrica/nostalgic EA/Changing_Culture.pdf>.

Peers, Douglas M., and Nandini Gooptu, eds. India and the British Empire. Oxford University Press, 2012.

Pletcher, David. “The Building of the Mexican Railway.” The Hispanic American Historical Review Vol. 30 (1950): 26-62

Van Hoy, Teresa. “A Social History of Mexico’s Railroads: Peons, Prisoners, and Priests (review).” The Americas 66.2 (2009): 297-298. Project MUSE.

Zgoda, Mason. “History of Indentured Servitude Between the 18th and 19th Centuries.” HubPages. HubPages, 3 Mar. 2013. Web. <http://masonzgoda.hubpages.com/hub/History-of-Indentured-Servitude-Between-the-18th-and-19th-Centuries>.

THE Way IT ALL STARTED

[youtube]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hOni0KUwza8&feature=youtu.be[/youtube][youtube id=”hOni0KUwza8″ align=”center” mode=”normal” autoplay=”yes” parameters=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hOni0KUwza8&feature=youtu.be”]

Gender Oppression, inequality and Gender Roles In India and Southwestern United States: How British Colonial Rule and American Internal Colonialism Perpetuated Gender Roles and Oppression

Gender Oppression, inequality and Gender Roles In India and Southwestern United States: How British Colonial Rule and American Internal Colonialism Perpetuated Gender Roles and Oppression

Photographs serve as a historical window into the past. Sentiments, feelings and societal customs can be physically manifested through the observation of photographical images. The digital collections in the Degolyer library at SMU, contain photographs of Indian people during the period of British colonialism, and Mexican Americans during the internal colonial struggles in Southwestern United States during the 1800s and 1900s. From these photographs, the history of gender roles, gender inequality and female oppression in India and the American Southwest can be observed. Traditionally, women have been placed at the margins of society, history and culture in patriarchal societies. These male dominated societies prevented woman from having opportunities to positively influence their nations and denied them the ability to enter the public sphere. Gender oppression and Inequality created negative and often times violent environments for both Indian and Mexican American women. Gender roles, inequality and oppression were traditionally a large part of society in both Southwest United States and India, and the introduction of colonial rule and internal colonialism perpetuated the institutions and practices that caused gender oppression.

India: Religious Gender Oppression and Colonial Law.

The basis for gender oppression in India can be accounted largely by both Hinduism and Islam, the two largest religious sects during British colonialism. According to Hindu doctrine, women where created by the Brahman to provide company for the men, and to facilitate procreation, progeny and the continuation of the family lineage. (Char 42) According to the Vegas, the role of a woman was simply to support the man, and enable him to continue his family tradition. In Islam, the Quran dictates that females are secondary to men. Muslim men are allowed to hit their wives, marry multiple wives, and can even get rid of an undesirable wife. (Char 43) The role that religion plays in India is palpable, and thus it is no surprise that the doctrines of gender oppression present in both Hinduism and Islam have strong influences in society.

Before British colonization, Indian society maintained practices that were entirely gender oppressive to woman. Such practices included sati, female infanticide, and child marriage; all practices that caused suffering, pain, and even death to the woman and girls involved. Sati, a practice observed through the rituals of Hindu nations, was the act burning alive the widow of a Hindu man. (Dakkessien 112) It was widely practiced by the upper Castes during the eighteenth century. In some Indian states, how many woman a prince took to the funeral pyre with him, served as a measurement of how many achievements he had made. (Dakkessien 113) Female infanticide was the act of killing newly born female infants, or killing a female fetus through selective abortion. The practice was widely acknowledged in India and was caused by poverty, dowry system, births to unmarried women, deformed infants, lack of support services and maternal illnesses. (Liddle 523)

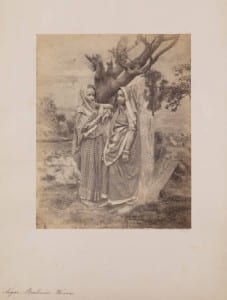

In the above image, two Nagar Brahmin “women” are depicted standing next to a tree in situated in an Indian plain. Close observation gives the impression that these women are actually girls. However, once a girl is married, she is deemed to woman according to Indian culture. However, these girls serve as a physical representation of the institution of child marriage present in India.

Colonization of India by the British was spurred by the East India trading companies profit driven intentions. Cotton being in abundance in India, it served as a catalyst for British invasion. The cotton supplies attracted the East India Company, who settled in India during the late 1700s. They began colonizing the Indian peoples in order to create a division of labor that could satisfy their production needs. Males in India where now subservient to a higher power, and thus women were subservient to both Indian males and British colonizers.

In 1858, the East India Trading Company transferred the rule of India to the British crown, which became the British Raj. At the start of her rain as the first Empress of India, Victoria created a British proclamation of non-interference in the customs and practices of the Indian people. However in the nineteenth century, British rulers removed Indian woman’s marriage and inheritance rights in the state of Kerala. This would serve as a bench mark for British legal influence in India. (Liddle 523)

Before and during the rule of India by the British, India implemented a hierarchal caste system, which delegated certain groups of people into different levels of status. (Char 43)The caste system was a patriarchal construct through which males observed overarching power over the female population, specifically females in a lower caste. (Betteille 490)The higher level of status denoted by the specific caste an Indian man was a part of provided him with the ability to abuse women in lower castes without consequence. The women in lower classes where subjected to violence, intimidation and public shaming in order to maintain the gender inequality. (Betteille 492)In each specific caste, the women associated where considered to be the bottom of that caste. Woman in the lowest caste, were literally the lowest members of society.

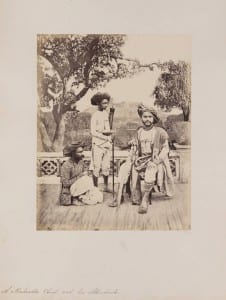

The above image represents how women where viewed as subservient to men. In the image there are two men and two women. The men are standing at the center of the picture while the women are seated at either side. The women appear to be at the feet of the men in the picture. This is symbolic of the of subservience that was expected of women in Indian society.

During British rule, the caste system became legally rigid. The British started to enumerate castes during the ten-year census and meticulously codified the system under their rule. (Liddle 524) Thus the British Raj did not spell reprieve of gender oppression for woman, but rather a stricter sense of it. The British believed that caste was the key to understanding the people of India. Caste was seen as the essence of Indian society, the system through which it was possible to classify all of the various groups of indigenous people according to their ability, as reflected by caste, to be of service to the British. While the caste system was regarded as a Hindu and societal custom, it was formed into law through British administration. Through the caste system, British rulers where able to subjugate the Indian peoples based on the caste they belonged to. (Liddle 526)By this action, men’s superiority over woman of a lower class was solidified in British colonial law. Where the British Raj succeeded in destroying institutions of gender oppression involving female infanticide and sati, it failed in releasing woman from gender oppression associated with the caste system.

The British influence in the caste system and the association of marriage served as a vehicle for gender inequality and oppression. Through British rule, male Indians in society were able to continue open gender oppression and inequality. Thus, Indian females were partitioned into an even lower role in society than was previously held before colonial rule.

The American Southwest: Gender Oppression and Roles Through Societal Structure and Internal Colonialism

In the American Southwest, the construction of female gender roles was engrained into the mind of girls at birth. While their fathers gave the boys a machete, the girls where given a metate and a malacate, stone instruments used to grind maize. With this initial act women were allocated into a feminine typecast in order to accent their perceived feminine qualities. (Schnieder 7) Gender and sex were viewed as homogenous qualities that could not be separated. Women were expected to conduct acts that were considered exclusively feminine, while the men took the roles in society that were considered masculine.

The above image contains a Mexican girl sowing on the doorstep to her home. The girl is affirming herself as a female and participating in a female orientated trade as dictated by Mexican society.

Internal colonialism in the American southwest served to propagate this sexual division of labor through the use of court mandates. In 1908, the United States Supreme Court upheld a state law that prevented women from working ten hours per day. This case, Muller vs. Oregon, upheld the law on the basis that a woman’s physical structure and performance of maternal processes prevented her from engaging in demanding labor practices. (Cases and Materials 156) Thus American law continued the female stereotype as a homely figure, with the ability to conduct feminine tasks exclusively.

For most women, marriage, motherhood, frequent pregnancies the care of large families, and the responsibility for household production molded daily existence. (Vigil 52) Labor practices included the production of food and goods that included preparing meals and sowing clothing.

The above image contains a mother taking care of her children while the children clean each other’s hair. This image is symbolic of the role that woman played in Mexican society. There is no man in the picture, suggesting that the woman’s husband is out earning for the family or engaging in the public sphere of society. Women where expected to remain home and take care of the family, while the husband goes out and engages in public works. Although their contribution to economic survival was vital, women’s social status remained secondary and supplemental to that of men.

Ever since the Spanish conquest of Mexico, women were seen as the source of evil and betrayal in society. This is due to the fact that La Malinche, a Mexican woman, became the interpreter for the Spanish conquerors, thus making their conquest possible. (Candelaria 2) This act of betrayal has influenced the thought process that any problems occurring in society are the fault of Mexican woman, a good scapegoat for a male-dominated society. (Schnieder, 3)Women were therefore confined to a life of subordination and silence at the feet of the patriarchy.

The stigma of La Malinche created an animosity towards woman that was influential in the prevention of Women’s participation in the public sphere. Women were refrained from participating in society and politics, and where not able to receive the same education that males in the society received. Women in Mexico were almost entirely restricted to the domestic sphere, as housewives and supporters dictated to them on the basis of their feminine sexual orientation. (Schnieder 4) As mothers and wives, they were expected to follow cultural, social, and political norms and stereotypes in order to fulfill the role that is imposed on them by society and which affirms them in their femininity. (Candelaria 5) This classification of woman as stay at home feminine subjects had consequences in that, any woman who raised her voice in the public sphere, possibly in a politically charged manner, ran the risk of loosing her female identity.

The prevention of Mexican women from engaging in occupations of civil life was condoned by the United States court system. In the case Bradwell vs. Illinois, The Supreme Court decided on a case involving a Mexican woman who was denied admission to the Illinois bar because she was a woman. (Cases and Materials 155)When the case was brought to the Supreme Court, Myra argued that the Fourteenth Amendment allowed women the right to practice law through the privileges and immunities clause. However, the court decided the right practice law was not provided by the clause, and thus woman were not allowed the opportunity to become lawyers. (Cases and Materials 156) In it’s language, the courts reaffirmed the gender stereotype attached to Mexican women in Mexican society. Women were stated in being naturally too timid and delicate to engage in the many masculine occupations of civil life, echoing the sentiments described in Mexican American society.

Similarities and Commonalities between Southwestern United States and India

Gender oppression and gender roles have been a part of Mexican and Indian societal tradition. In both Indian and Mexican culture, women where considered to be subservient to their male counterparts. In both cases, either by religious dictation or cultural custom, the females in society were expected to be serve as child barrers in order to propogate the family lineage of her male counterpart. In india, this was dictated by religious law, and in the American Southwest, societal customs prevented women from engaging in practices that where deemed masculine. The stigma of La Milinche created a negative attitude toward publicly engaging Mexican women, which closely paralleled the second class citizenship applied to Indian Women through the Caste system.

With the introduction of both British colonial rule, and American internal colonial domination, gender inequality was perpetuated. The British Raj not only allowed the Caste system to stand, but used it as a legal basis for Indian subjugation, thus subjucating Indian women on a larger scale than was previously dictated. Similarly, the United States Supreme Court decisions during the 1800s and 1900s reaffirmed gender stereotypes that where prevalent in Mexican American culture. So while gender roles, inequality, and oppression was traditionally prevalent facets of both Indian and Mexican American society, colonial and internal colonial rule not only continued these practices, but perpetuated them in way that adversely affected the Mexican American and Indian female populations.

Works Cited

Beteille, Andre. “Race, Caste and Gender.” Man 25.3 (1990): 489-504. JSTOR. Web. 30 Apr. 2015

Bradwell v. Illinois. 83 U.S. 130. Supreme Court of the U.S. 1872. Print.

Char, Desika. Hinduism and Islam in India: Caste, Religion, and Society From Antiquity to Early Modern Times. Princeton: Markus Weiner, 1993. Web. 30 Apr. 2015.

Dakessian, Marie. “Envisioning the Indian Sati: Mariana Starke’s ‘The Widow of Malabar’ and Antoine Le Mierre’s ‘La Veuve Du Malabar'” Comparative Literature Studies 36.2 (1999): 110-30. JSTOR. Web. 30 Apr. 2015.

Liddle, Joanna. “Gender and Colonialism: Women’s Organization Under the Raj.” Woman’s Studies Int. Forum 8.5 (1985): 521-29. 30 Apr. 2015.

Muller v. Oregon. 208 U.S. 412. Supreme Court of the U.S. 1908. Print.

Vigil, James Diego. From Indians to Chicanos: The Dynamics of Mexican American Culture. Prospect Heights: Waveland Press, 1984. Web. 30 Apr. 2015.

The Exploitation of Colonialism

The Exploitation of Colonialism

One of the most important lessons of History is that it should never be forgotten. While ancient books and literature have been the cornerstone to remembrance, they are not as real as a photograph. Photographs capture history and allow an audience to see through the eyes of the photographer in that time period. Through photographs, it is impossible to ignore the devastating effects that European settlers had upon both the American Southwest and the Indian Ocean World. Both India and Mexico were less developed nations, and both appeared to live in a different time and age than their European invaders. By the use of photographs, it is easy to capture the similar effects of European Colonialism in India and Mexico. These Spanish and British explorations ultimately stripped both native lands of wealth and led them into brutal war.

When the British arrived in India, their economic mentality abruptly shifted the wealth distribution in the country. In the 17th century, the British settlers established the East India Trading Company, which was a trade company that actively sought and dealt Indian-based commodities. At this time, India was far less developed economically to a point where native Indians did not have competitive mindsets in their marketplace. On the other hand, the British were seeking nothing more than profits. India, as a nation, was not ready to compete with British traders, and because of this, wealth began to flow out of Indian pockets and into the British wallets. The wealth balance shifted to an extreme extent, which is found in Photograph 1.

Photograph 1:

Photograph 1 is an old photo taken from India. The image is of the tombs of the early English settlers. The buried settlers are speculated to be brothers, Christopher Oxenden, Sir George Oxenden, first governor of Bombay, and Gerald Aungier, the third Governor of Bombay. They are resting in what clearly is a gigantic tomb with spectacular early Indian architecture that almost resembles the Taj Mahal. These graves of early English Colonialists are not only immense, but they are crafted with beautiful detail. These settlers had to be extremely rich. Their riches were earned when they settled in India and took over their commodity market. The settlers knew how to make money when they arrived, and they profited quickly.

The British trading mentality struck India by surprise, and brought out a concept of Globalization that impact Indian culture and markets. Globalization is when separate nations integrate marketplaces together and combine economic cultures. The integration of two societies is not as easy as it sounds. A Nova South Eastern University study suggests that Globalization will cause “[change] in the culture of host communities.1” As the East India Trading Co began to take over India, the company literally had to take over the Indian society. They began by collaborating with Indian merchant capitalists. The British established trade marketplaces such as Bombay, Madras, and Calcutta. They quickly realized wealth in trading Indian Textiles and Silver. Essentially, the English were taking control over most of the revenue in the country. This tactic of Globalization is an idea that is widely used in many other colonial societies.

Like the British settlers, Spanish settlers sailed in search of a new world to find riches. Only they this time, they landed unexpectedly onto a whole new continent, America. As Spanish colonialists moved into the Native American villages, they too saw opportunity for wealth. They capitalized over the Native Americans by implementing rules of the Catholic crown. They slashed the natives’ traditions and set down the three standards known as ‘Requiremiento’, ‘Encomienda’, and ‘Reportimiento.’ ‘Requiremiento’, or requirement, was a rule that forced all Natives to convert to Christianity. ‘Encomienda’, or entrustment, was a call for a system where both societies are working together for the crown. In essence, ‘Encomienda’ was a way to trick the Native Americans into trusting the Spaniards with the profits and sales of resources. The final tactic used by the Spanish settlers was the enactment of ‘reportimiento’, which meant labor distribution. This rule was a bogus trick for the Spanish settlers to have the Natives work for them for little cost. The scheme gave the Spanish a complete economic advantage over the Natives as they found themselves having to do little work, and still being trusted with all of the money. This led to the Native Indians being overworked. These terrible rules put the Native Americans in a set back. What eventually turned into Mexico was a society where labor was intensive, and little paying. Photograph 2 shows an example of a poor Mexican girl working in the year 1902.

Photograph 2:

Photograph 2 is an example of the economic state that Mexico was left in during the Post-Colonial era. The aftermath left Native Mexicans in a economically deprived state where locals made a living doing simple jobs, such as basket weaving and making straw hats. This is at the same time when the Industrial Revolution hit the United States and Great Britain, and their economies and job markets were booming. Spanish settlers globalized the Southwest American economy, but when they did it, it became less economically efficient, because of their use of oppressive policies. The policies left Mexico in a state where the top class citizens (Spaniards) could make money, while the majority of the population, in the lower class could not. A research paper published by the Social Science Diliman analyzed the effects colonialism had on the Mexican economy. The report explains that colonialism in Mexico established “monopolistic privileges over peripheral land, labor, production, [and] trade.2” The article explains that by creating a “decline of traditional societies,” Mexico’s economy suffered and fell to “corruption”. The Diliman uses corruption as a substitute for what really is wealth-inequality. Photograph 2 depicts what life was like for a typical lower class girl, while the rich Spaniards who ruled the country held all the wealth without intense labor.

What was first Colonialism has shifted into economic takeover. This is clearly seen in India and Mexico. Photograph 1 shows an astonishing photo of the magnificent graves of not Indian leaders, but of early British settlers, who created and ruled the very trade-marketplaces that shifted the Indian wealth balance. Likewise, Photograph 2 shows a representation of the economic disparity in Mexico. There is a clear correlation showing that forced implementation of rules through colonialism negatively impacts the societies of the countries invaded. When economic disparities are present, it leads into revolts, which then lead into war.

When a country colonizes in a new territory, it is exploration, but when they colonize in a new inhabited territory, it is Imperialism. Imperialism is when a country not only conducts expansion over an occupied territory, but uses military force to acquire land. This is present when British took control of India, and when Spaniards colonized in the American Southwest.

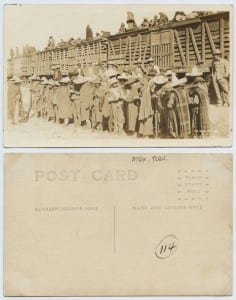

Military power was the primary factor in territorial shifts in the American Southwest. Spanish settlers made large expansions following Hernan Corté’s victory over the Aztec Empire in 1521. This led to Spain establishing major cities throughout “New Spain” or what is modern day Mexico. But the fighting was far from over. Nearly four centuries after the fall of the Aztec Empire, Mexico’s years of wealth inequality led to a civil war. In John Hart’s Revolutionary Mexico: The Coming and Process of the Mexican Revolution, Hart explains the real motives behind the revolution. He further explains that “an economic system dependent on foreign capital imports that failed to absorb a displaced peasantry and reduced artisan class” all cumulated to the savage fighting3. Essentially, citizens were fed up with living in a country that relied on imports and failed to create a productive economy to help the lower classes. Photograph 3 depicts Mexican Revolutions standing in a line, posing for a photo.

Photograph 3:

The above photo contains a lot of emotions from the rebellious Mexicans. Each man standing sports a Sombrero, ammunition chains and a furious mustache. These men are proud Mexicans, who are willing to fight for the poor who have been suffering at the hands of Aristocratic rulers. The Mexican revolution was the last straw of oppressive policies that started centuries ago by the Spanish colonialists. The ammo wrapped around each man symbolizes how serious and dangerous this war is. The Spanish army was a force to be reckoned with in the eyes of these revolutionaries. Photograph 4 is of a graveyard of 63 dead Mexicans from a large unspecified battle.

Photograph 4:

The graveyard seen above is of only one battle that took place during the revolution. The Mexican Government’s use of military force put revolutionaries on the brink of death. It is estimated that roughly 2 million Mexicans were slaughtered in the war4. By use of a Mexican army to enforce law and territories, imperialism was ongoing in Mexico at the time. The economic downturn, created by the aristocratic Mexican government, lead the country in a civil war and not even military force could stop the fight against oppression. Imperialism in the American Southwest accumulated into a series of civil wars and fights that inevitably left the Spanish-Mexican army wounded. The American Southwest is only one example of a territory dictated by Imperialism and military force.

Like Mexico, India was subjugated by military power and colonial domination. In 1857, one of the most brutal rebellions occurred in India. At this time, the East India Trading Co was still in control of India, and it was actively enlisting Indians to fight in the British army. But problems ensued when the British forced Indian soldiers to fire bullets that required them to bite pork fat casings off of each bullet. The Indian soldiers found this unacceptable. Many Indians identify as Muslims, and in their culture, consuming pork is forbidden. The enlisted Indians were not going to put their religion behind their loyalty to the British. This sparked the Indian Rebellion of 1857. Military power was the key for British combatting the revolution. In a History Today article, an Indian rebel described the brutality of the British military force. He explained that when his rebel group’s position was compromised, they saw “English forces [appear] on all sides,” and “Bullets and cannonballs rained down” upon them5. In a little less than a year, the British finally suppressed the rebels. They punished the insurgents, as seen in Painting 1.

Painting 1:

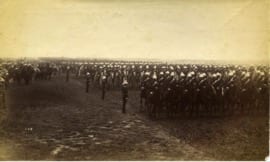

The above painting depicts Indians in front of cannons prepped to shoot straight through them. The British did not apologize to the Indians for disgracing their religion, but instead they killed the rebels as punishment. The British continued to use military force as a means to control over India. The newly placed Raj increased their military after the revolution. British imperialized India, as they began investing roughly 50% of revenues into the Indian Army. Photograph 5 is a photograph of the new Indian Army post-revolution.

Photograph 5:

The above picture shows hundreds of thousands of Indian soldiers wearing the British uniform. The Indian army was the largest army in the world at this time. The British oppression that led the entire India ocean world into a rebellion was once again restored as Indians continued to serve the British.

Both the American Southwest and India broke into rebellion. Their causes were similar as both countries suffered at the hand of their European conquerors. Photographs 3 and 4 both symbolize how dark Mexico became. The band of Mexican revolutionaries appeared very determined to fight against their oppression. Likewise, Painting 1 and Photograph 5 show the brutality of the British army. Colonialism was established with the use of military force to maintain control of society in both countries, and it eventually lead to civil war in India and Mexico.

European colonization turned from a great idea for countries to explore the world and make money, to a globalizing and imperialistic rule that led to economic oppression and revolution in its host countries. The Spanish sailed to the New World, dominated Mexico, and forced its own country to revolt by creating a huge wealth equality gap. Similarly, English settlers ventured to India, dominated the trade markets and dehumanized the native Indians to the breaking point of revolution. Colonialism is a topic that should never be forgotten. It is critical that we never forget what happen so we may understand the hardships still found in both countries today and not repeat the tragedies brought upon both nations.

Footnotes:

1 Kasongo, Alphonse. “Impact of Globalization on Traditional AfricanReligion and Cultural Conflict.” Journal of Alternative Perspectives in the Social Sciences 309-322 2.1 (2010): 309-22. Web. http://www.japss.org/upload/16._Kasongo%5B1%5D.pdf 29 Apr. 2015

2 Nieto, Nubia. “Corruption In Mexico: A Historical Legacy.” Social Science Diliman 10.1 (2014): 101-116. Web. http://connection.ebscohost.com/c/articles/96910015/corruption-mexico-historical-legacy 29 Apr. 2015.

3 Hart, John M. “The Crisis of the Porfirian Political Economy.” Revolutionary Mexico: The Coming and Process of the Mexican Revolution. Berkeley: U of California, 1987. 185. pag. Print.

4 McCaa, Robert. “Missing Millions: The Human Cost of the Mexican Revolution.” University of Minnesota Population Center (n.d.): n. web. http://www.hist.umn.edu/~rmccaa/missmill/mxrev.htm 29 Apr. 2015.

5 Coohill, Joseph. “Indian Voices From The 1857 Rebellion.” History Today 57.5 (2007): 48-54. Web. http://connection.ebscohost.com/c/articles/24957088/indian-voices-from-1857-rebellion 29 Apr. 2015.

Industrial and Cultural Progress

Colonialism is accurately described throughout history as oppression of the worst kind, one where those who are colonized are ruled in their own land and without much of a say in any cultural or legal matters. The colonial histories of India and Mexico, respectively, should be viewed through racial, cultural, and monetary lenses. As Darwinism began to find a foothold in European thought processes, global powers like England and Spain sought to expand their territories through colonizing poorer, ‘effeminate’ countries by exerting power through money and influence. Specifically, England ruled over India through its brokering with the East India Company in an attempt to take advantage of the seemingly rich land that they came across in their travels, summarized well by Edward Said in his trailblazing novel on Orientalism: “The Orient was almost a European invention . . . the place of Europe’s greatest riches and its oldest colonies . . .” (Said 1979). Similarly, Spain traveled to Mexico in hopes of discovering the mythical cities that contained power and money they thought they deserved. Through colonization, Mexico and India were oppressed, but at the same time, they learned valuable lessons that eventually became the foundation of their individual quests for full autonomy. As the decades passed by, the two colonies eventually found power and innovation in themselves, realizations that would have most likely never occurred had they ruled themselves freely throughout history. Evidence of these progressions, via photographs and beginning with the Industrial Revolution, throughout history provides the reader with proof of advances in technology and infrastructure, along with images of actual emotion stemming from social injustices, that are vital to the present day cultures established by both former colonies.

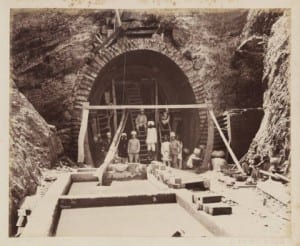

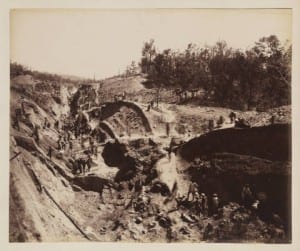

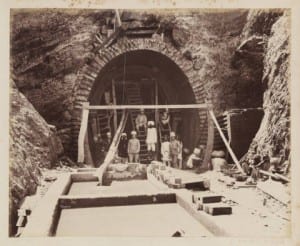

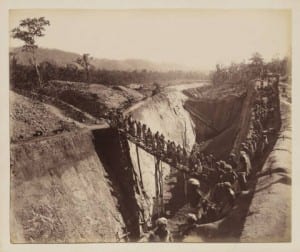

The Indian Ocean World, before the introduction of trade companies and capitalism, was a vibrant part of the world, full of wealth agriculturally, culturally, and in textiles as well. Much to the chagrin of native Indians, those very attributes would attract European powers seeking to expand their spheres of influence and increase national wealth as well. Specifically, around the middle of the 19th century, an idea coined ‘The Great Divergence’ was set in motion and defined the next century for Europe and Asia. Europe, especially the British, began to move towards industrialism through advances in technology, while Asia, namely India, did not. Fueled by exceptionalism and Eurocentrism, the British were able to exert more influence over the Indians as they obtained more powerful guns and access to non-traditional effects not seen before in India: “Europe’s economic progress was outstripping that of the rest of the world so that it had become the clear economic leader well before the Industrial Revolution . . .” (Studer 2008:393). However, because of this clear divergence in progresses, one can argue that India benefited greatly from the period of British oppression. The photo of the Indian and British workers constructing the Bengal-Nagpur Railway provides evidence of the first industrial progress in India, confirmed by M.S. Rajan: “There was a strong reaction . . . in India . . . a reaction which stimulated a renaissance in Asia. . .” (Rajan 1969:90). The construction of this railway eventually led to its assimilation into the Great Indian Peninsula Railway, and then the Central Railway seen throughout India today. Commissioned by British Parliament in contract with the East India Company, the railway might have initially benefitted the English in their pursuit of global influence, but the native Indians are the people who now reap the rewards of industrial progress. The construction of railways produced a price divergence in India alone, seen in the grain market through large price increases and, therefore, greater profits for the native Indians. Without being forced to construct railways in the first place, India might have never achieved the industrial progress seen in their quest to achieve independence.

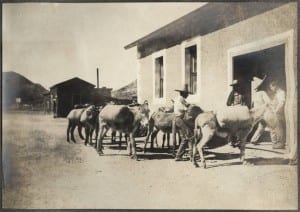

Similar to the plight of India, Mexico experienced a period of colonization by the Spanish empire after their journey for riches in the New World quickly turned into an easy path through Mexican territories of conquering and destruction. The entire goal of the conquests to the Mexican Southwest centered around the riches hidden in the cities and the lack of Western faith in those lands. The friars were sent directly by the Crown to go into those Mexican cities and convert any non-believer to their esteemed religion. However, those friars would encounter a few different types of Mexicans that made their enterprise very difficult. The ‘friendly’ Mexicans were of no trouble, and the Tlaxcalan tribe even aided in the attack on Tenochtitlan. The ‘hostile’ and ‘sullen’ Indians proved tougher to deal with, especially the sullen ones when it came to the spiritual conquest. Instead of directly attacking their ‘teachers,’ the sullen Indians would just discretely disobey the friars, thus making it extremely tough for them to achieve their goal of mass conversions. Although the British and Portuguese were not enforcing religion on the Oriental Indians, they had to be thankful that they were dealing with ‘sedentary’ Bengali. The rebuttal of the Spanish conquests by the native Mexicans greatly aided their quest to free themselves of oppression, and eventually spurred an industrial revolution of their own accord—one very similar to the progression of the colonized people in India. The construction of railways in Mexico galvanized the Mexican Revolution that occurred, following the expulsion of the Spanish, as Americans began to infringe on Mexican borders themselves. The picture above, “Ranchmen bringing corn to town on burros,” shows Mexican ranchers having to transport their goods via burros, traveling often from the arid countryside and back to their villages. The construction of the Mexican Railway allowed the natives to efficiently and safely transport their precious goods, including food and crops to sell, through the previously treacherous climate seen throughout Mexico. However, before they reached industrialization, they had to figure out how to properly harness the technological advances seen throughout Europe that had not yet made it to the New World: “Nineteenth-century tourists to Mexico carried away with them the memory of execrable roads and wretched travel conditions” (Pletcher 1950:26). Without the aid of visual evidence of these harsh travelling options available to Mexicans during the middle of the 19th century, one would never know that industrialization was truly necessary. However, the impact of Spanish rule and technology on the Mexicans remains important today. Had the Mexicans not been subjected to the culturally and technologically advanced Spanish, they would not have deemed themselves inefficient with regards to the changing times. More prominent is the fact that burros and antiquated coaches would have remained the norm throughout Mexico, a realization that becomes more damning when considering how divided the Mexican cultures originated as. The eventual unification and independence of Mexico would have never been possible without their introduction to the new technology brought over by the colonizers from Spain.

Another important factor in Indian, as well as Mexican, cultural and personal advancement stems from the European based infrastructure. The improved infrastructure, ranging from academia—like the Grant Medical Building seen above, to construction of religious monuments, resulted from the British putting the native Indians to work throughout the colonized land. The building itself clearly shows a European influence in its architecture, and most of Bombay itself became covered in ideals coming from British thoughts: palm trees were planted, the previously mentioned railways, and a focus on improving quality of life are all evident through visual analysis. Specifically, the British seemed to want to provide the opportunity for Indians to learn and, therefore, treat medical problems that arose during colonization. The Grant Medical College, standing tall in stature in the photograph and in its reputation as well, now consistently ranks in the top 10 healthcare centers throughout the world. One must consider that without the British insistence the natives learn about the medical profession, India would not be as well respected as they are today for their contributions to healthcare. While Indian infrastructure facilitated a rise in personal welfare for the country as a whole, the Mexican infrastructure centered around their furthering national industries and the reputations they carried outside of the Mexican borders. Specifically, Mexico saw a rise in the amount of jobs and the specialization increases that accompanied them. However, it must be noted that during, and after, the middle of the 19th century, Mexico was no longer influenced by the Spanish empire; now, they had to prepare themselves for the upcoming border war with the expanding, fledging United States of America. Under the leadership of Porfirio Díaz, Mexico began a period of ‘positivism’ and restructuring of their economy and infrastructure. The foci of this “Paz Porfiriana” centered around cultural stability and improvements in the areas of mines, railroads, and farming. An important photo that provides some context for these advancements is “Viaducto de Jajalpa,” taken by Abel Briquet. This still photograph of a locomotive crossing a ‘viaducto’ in Mexico contains no people, but it contains a deeper meaning nonetheless. In the photo, one clearly sees the steam locomotive and the intricate bride it crosses over. The only action perceived to take place here is the train carrying supplies somewhere important, either for the native Mexicans or for some other purpose. One notable observation that can be made from this photo comes from the idea that this furthers the Mexican industrial progress, making it comparable to India’s industrial revolution. Secondly, one can assume that the locomotive itself was a huge relief in its’ ability to quickly and largely deliver goods from one rural town to another throughout Mexico. The architecture of the ‘viaducto’ is also very impressive, prompting one to both compliment and question the creator of such a project at the time. To conclude, a viewer might ask who did build the bridge—natives or outside influences; as well as asking what the train is actually carrying and for whom. Such a structure became vital in the transportation of coal miners and farmers, as well as the important goods they collected. The construction of a viaduct and implementing a more inter-connected Mexico through railways aided their growth in infrastructure, and was directly impacted by their need to further themselves in the face of an impending border struggle with the United States. The industrialization of India and Mexico allowed both to eventually overcome colonization through social rebellion, acts that were fueled by improved confidence and a newfound sense of nationalism.

Race is an issue that has plagued every civilization, legitimized by the leaders of colonizing societies, and often enraging those affected by it. This theme is exactly what was exhibited in the colonial empires seen in India and Mexico. The colonial revolts that took place in the British-ruled India and the territorially challenged Southwestern United States differed in foundation of ideals, but appear very similar when viewed from a strictly nationalistic point of view. Specifically, both the native Indians and expansionary Hispanics were fueled by their desires to better their peoples and increase the amount of influence they could achieve on their own, goals that were galvanized through decades of colonialism. However, they approach these ends by highly different means. The Indian photo of the Bombay policemen highlights an important idea within their struggle for independence: internal colonialism. The policemen look sedentary and effeminate, falling in line with British portrayals of native Indians. While they may have been given the title of ‘policemen,’ they were really just extensions of British rule within the townships. This idea of internal colonialism remained intact throughout their fight for freedom. Following the Sepoy Rebellion in 1857, the Indians started to establish a precedence for independence; however, Gandhi eloquently summarized their continued plight in the face of increased hope: “. . . India has become impoverished by their Government . . . We are kept in a state of slavery” (Gandhi 27). However, as borders became even more muddled when religious revivalism morphed into dissident factions battling one another. Although the Indians did achieve independence in 1957, they continued to harbor internal colonialism within their communities. The ‘Swaraj’ movement was affected by the disdain shown by the Hindus and Muslims towards each other, a difference not even Gandhi could aid—proven in his eventual assassination by a rivaling RSS group.

The Hispanic mission did not deal with any religious tensions, per se, but they were very similar to the border-specific battles fought by the native Indians in their colonial revolts. Essentially, the Mexicans saw Texas as its own land and inhabitable by whomever, at a price. They were not saddled by religious problems, but territorial problems. This rivals British views of India as a land in need of governing. The collision course of the American settlers and exploratory Mexicans was inevitable given the respective westward and northern expansions of the two, and began to culminate around the passage of the Adams-Onis Treaty. The United States more than doubled their land claims by acquiring Florida, the Louisiana Purchase, and the subsequent California gold rush. Mexicans could only watch as Americans crept closer and closer to their borders. Fearing huge losses, both territorially and culturally, the Mexicans reacted violently as more Americans came to the ‘Republic’ of Texas, thus beginning the Mexican Rebellion. The photo of Mexican soldiers boarding trains to battle Americans highlights the continued influence of colonialism and the improvements inspired by oppression. Without the trains, the Mexican troops would have continued travelling by burros and other inefficient means. The trainloads of soldiers also furthered ideals of nationalism and hopes for conflict-free lives. However, such a reaction had an inverse effect compared to the Gandhi-led, non-violent Indian rebellions, as it actually inspired Anglo-Saxon nationalism and hurt the Mexican efforts in the long-run, as they eventually ceded Texas to the United States.

The nationalism movements that eventually led the individual colonized nations to independence took different paths, but both were direct descendants of the lasting effects from colonization of Indian and Mexican lands. Evidence of the vital, internal progressions throughout history assuredly give the reader proof of advances in technology and infrastructure, along with images of actual emotion stemming from social injustices. Without the influence and colonization from Spain, Britain, and the United States, Mexico and India would not have reached the cultural and nationalist goals they had to set for themselves.

Works Cited

Andrabi, Tahir and Michael Kuehlwein. “Railways and Price Convergence in British India.” The Journal of Economic History Vol. 70 (2010): 351-377. Print.

Gandhi. Hind Swaraj. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1997. 27. Print.

Gauss, Susan. “Made in Mexico: Regions, Nation, and the State in the Rise of Mexican Industrialism, 1920s-1940.” The Hispanic American Historical Review Vol. 92 (2012): 574-575. Print.

Pletcher, David. “The Building of the Mexican Railway.” The Hispanic American Historical Review 30.1 (1950): 26-62. Print.

Rajan, M.S. “The Impact Of British Rule In India.” Journal of Contemporary History (1969): 89-102. Print.

Said, Edward W. Orientalism. New York: Vintage, 1979. 60-80. Print.

Studer, Roman. “India and the Great Divergence: Assessing the Efficiency of Grain Markets in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century India.” The Journal of Economic History 68.2 (2008): 393-437. Print.

Village Culture, Urbanization, and Colonial Legacy

History can be interpreted through different mediums: language, print, art, or photographs. In his article, “The Material and Visual Culture of British India,” scholar Christopher Pinney argues that visual culture, which encompasses any graphical or pictorial form of expression, is not a “superstructure”—that is, an outcome of prior political or social action—but a representation of culture itself (Peers, 232). We tend to think of a photograph as a mere portrayal of its contents: people are just people, landscapes are just landscapes, and buildings are just buildings. But analyzing a photograph is much like reading between the lines in a book. The same way we study authors, we must scrutinize photographers’ motives for taking certain pictures. The same way we look for literary devices in our books, we must examine the facial expressions, fashion, and backgrounds in photographs. Visual culture shows us history; we use history to recreate the past and qualify the present. India and Mexico both endured colonization periods. Though these two present countries exist in different hemispheres, India and Mexico still share vast similarities, especially in the ways their peoples, past and present, experience colonial legacies. Using photographs, we can analyze these similarities. Photographs of Mexican villages exhibit culture and transformations incurred from colonialism; and photographs of Indian law enforcement reflect the effects of urbanization and colonial neglect.

http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/ref/collection/mex/id/676

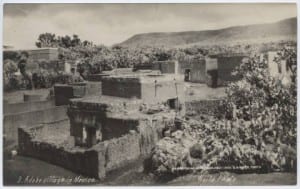

C.B. Waite’s photograph titled “Adobe village in Mexico” and dated 1904, shows only two people in the far middle third. The couple looks unsuspecting; perhaps they did not know the photographer or his purpose. The photograph shows a village of adobe houses surrounded by shrubs, trees, and nopales. Moreover, a series of hills, or cerros, covers the distant background. The picture shows no activity. Maybe, mothers are in their homes while men work in the fields and children attend schools. Families may be in their homes altogether; or, the houses may be abandoned. The adobe houses do look dilapidated, and the corrales (pens) do not have any animals. We can deduce, then, that the inhabitants of this village do not possess much wealth. The photograph still leaves some questions unanswered: Where are the rest of the village members? Are the houses actually abandoned? How do these two villagers practice their family structure?

http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/ref/collection/mex/id/521