Amun Taharka

KNW 2399

30 April, 2015

Visual Culture Analysis: The Contents of an Image

What is contained in an image? The word image is defined as the physical representation of a person, place, or object according to dictionary.com.1 However, anyone who has seen any of Pablo Picasso’s famous paintings, or anyone who is an artist his or herself would contend that much more is contained in an image. Representations of people and places contained in images generate and facilitate emotions, attitudes, and ideas regarding what is being visually represented. Because of the unique ability of images to impact viewers in this way, their use as tools for propaganda throughout history has allowed for photographs to have unique impact on culture and history. Images of colonial India and of post-colonial Mexico generated and spread stereotypes regarding race and gender in order to justify the colonization and exploitation of India by Britain, as well as the mistreatment of Mexican people by Anglo-Americans. The use of photographs as a tool to drive the process of colonization relates to the histories of both India and Mexico.

Colonial India

Orientalism is a set of beliefs created by Europeans in an attempt to label and understand a rich Indian culture which was vastly different than their own. This view depicts Indian people as mystical, and mysterious. Rajeswari Sunder Rajan sums up this view in his article entitled, After ‘Orientalism’: Colonialism and English Literary Studies in India, in which he writes, “Serving as the ‘other’ of Europe, [India] is seen as variously strange, mysterious, corrupt, beautiful, decadent…while fulfilling a variety of European desires” (23).2 The view of India as the “other” created a desire to explore and eventually exploit a new, mysterious land. In addition, negative perceptions about Indian women specifically are included in Orientalist ideology. In Indian culture, the harem is known is both the women in a family but also as a home or sanctuary. However, the harem inaccurately interpreted by Europeans as a symbol of promiscuity and orgiastic sex. Such stereotypes contribute to the dehumanization and objectification of Indian women as well as a perceived lack of morality amongst Indian people. Images and photographs which portray these stereotypes of Indian people contributed to the internalization as well as the distribution of Orientalist attitudes.

William Johnson’s photograph, entitled Brahmin Women of the Konkan, demonstrates how Orientalist ideas can be captured and distributed by a picture.3 Both of the women in the image are looking away from the camera, and are photographed at odd angles with respect to the camera and the viewer. This draws the viewers’ attention away from the women, seemingly in order to portray them as objects of a viewer’s gaze as opposed to people at the center of a photograph. The large building in the background as well as the fact that the women are standing in the bushes adds to the objectification of the Indian women in this picture. The portrayal of the women in this picture as objects in the midst of a busy landscape illustrates Orientalist ideas because it dehumanizes them and creates mystery about them. Because the women are wearing the popular traditional Indian Saris, the portrayal of the women in this picture extends to Indian women in general.

Included in Orientalism is the view of Indian men as lazy, effeminate, morally corrupt, materialistic, and unfit to lead or take charge. This attitude is evidenced by Robert Clive’s speech to the House of Commons in Great Britain when he states, “The inhabitants, especially of Bengal, in inferior stations, are servile, mean, submissive, and humble. In superior stations, they are luxurious, effeminate, tyrannical, treacherous, venal, cruel” (Curtis and MacDowell, 809).4 Clive’s generalization of Indian men was served the purpose of justifying greater control of the region of Bengal by the East India Company.

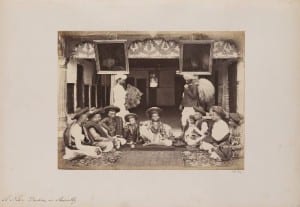

An additional photograph by William Johnson demonstrates the ability of images to spread such attitudes. This image depicts a Durbar, which is an assembly held by an Indian prince.5 Due to the lavish carpet designs, elegant clothing, servants, paintings, and the pillar contained in this image, it makes sense that this is a meeting amongst royalty. Interestingly, everyone in the image has a blank facial expression, appearing to be sitting quietly. The man at the center of the room who is being tended to by the servants, who appears to be a Prince, has an indignant, condescending expression on his face. Such imagery communicates that these men live lives of luxury, and laziness. The men’s lack of expression as well as their averted gaze suggests that they are effeminate. Men are typically portrayed as dominant figures who are the center of attention. Additionally, the appearance of servants in the image also communicates laziness and moral corruption amongst the elite in India. Robert Clive utilizes these perceptions in his letter to William Pitt when he states, “…they [people of India] would rejoice in so happy an exchange as that of a mild for a despotic government” (Keith, 15).6 Clive demonstrates through his statement how stereotypes regarding Indian people and culture were used to justify British colonization. The communication of such attitudes through imagery reinforced these same ideas, contributing to their spreading as well as their use for the purpose of colonizing India.

Post-Colonial Mexico

For as long as Mexico has been a country, Mexicans have faced and arguably still face oppression by Anglo-Americans partly as a result of the spread and internalization of negative stereotypes. In his book Chicano! The History of the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement, F. Arturo Gonzalez explains, “An early source of Anglo-American antipathy towards Hispanics is found in the ‘Black Legend’. This interpretation has sixteenth-century English propagandists discrediting the reputation of Spaniards in the New World in order to further their imperialistic plans. As a consequence, Anglo-Americans held negative views even before confronting Mexicans on New Spain’s frontiers…”(5).7 Gonzalez’ statement suggests that due to stereotypes regarding Spaniards in the New World, that Anglo-Americans held negative views regarding Mexicans before ever encountering any. The negative views regarding Mexicans held by Anglo-Americans were detailed by former U.S ambassador Joel Poinsett, in his article entitled: The Mexican Character. In this article, Poinsett claims, “They are laborious, patient and submissive, but are lamentably ignorant. They are emerging slowly from the wretched state to which they had been reduced; but they must be educated and released from the gross superstition under which they now labour before they can be expected to feel an interest in public affairs” (2).8 Poinsett’s statement highlights the attitude of Mexicans as being submissive, ignorant, and uneducated. As a result of such stereotypes, Mexicans were treated as second-class citizens by Anglo-Americans. In his book Chicano! The History of the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement, F. Arturo Gonzalez illustrates this effect when he explains, “In essence, it is true that because of an Anglo-American unwillingness to accept Mexicans as equals, they often ignored treaty agreements that gave Mexicans all the rights of citizens” (6).7 Due to the negative attitudes towards Mexican people held by Anglo-Americans, Mexicans were denied their rights as citizens.

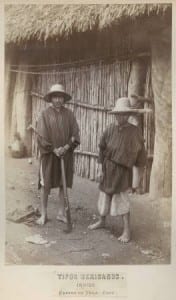

Similar to the spread of British Orientalism, images of Mexicans were propagandized to create and distribute negative perceptions of Mexican people. One example is Abel Briquet’s photograph entitled Tipos Mexicanos. Indios Estado [sic] de Vera Cruz.9 In this image, the two men are both standing barefoot on scattered debris, outside of a simple dwelling made up of sticks. Additionally, the men are dressed in very simple clothing, and one of the men is posing with a gun in his hands. The bare-feet and simple clothing signify that these men are of low economic class and lack of education, reinforcing this perception of Mexican people. The gun, as a symbol of violence, communicates ignorance, lack of education, as well as a lack of order in Mexican society. This image captures and reinforces the perceived “wretched state” in which Mexican people live, as described by Joel Poinsett.

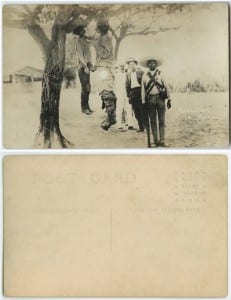

Another example of the negative portrayal of Mexicans through images appears in the form of the above photograph, depicting an execution taking place in Mexico.10 In this image, two people are being executed: one of which appears to be a child and the other an adult. The hanging of these two Mexicans from a tree implies that these people were being punished. However, behind the tree, several men who appear to be wealthy, Anglo-American are standing by watching the men hang. Also, standing next to the hanging bodies, a Mexican soldier stands at attention, as though he is carrying out orders for the seemingly wealthy and powerful men standing behind him. All of these details contribute to a symbolic representation of superiority and authority of Anglo-Americans over Mexicans, reinforcing the mistreatment of Mexican people. Such portrayals of Mexicans in relation to Anglo-Americans create and spread the perceptions used to justify the oppression of Mexican people.

Renowned photographer Terence Donovan once said, “The magic of photography is metaphysical. What you see in the photograph isn’t what you saw at the time. The real skill of photography is organized visual lying”.11 In the histories of colonization of India by Britain as well as Mexican oppression by Anglo-Americans, photographs visually spread lies in the form of inaccurate stereotypes regarding race and gender. This distribution of misinformation in reference to Indian and Mexican culture was allowed oppressors to justify the exploitation, oppression, subjugation, and mistreatment of people. What is contained in an image? The power to capture the past while simultaneously shaping the future.

Endnotes

1. Dictionary.com. Dictionary.com. Web. 30 Apr. 2015. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/image

2. Rajan, Rajeswari Sunder. “After’Orientalism’: Colonialism and English Literary Studies in India.” Social Scientist (1986): 23-35. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=qvGgsGBFQncC&oi=fnd&pg=PR9&dq=Chicano!+The+history+&ots=fXH5Wb8WgQ&sig=46cMA0MtqUMraTM5-L07660qlKg#v=onepage&q=Chicano!%20The%20history&f=false

3. Johnson, William. Brahmin Women of the Konken. Digital image. Europe, India, and Asia- Photographs, Manuscripts, and Imprints. 1 Jan. 1855-1862. Web. http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/eaa/id/729/rec/24

4. Curtis, Edmund, and Robert Brendan MacDowell, eds. Irish historical documents: 809-811. New York: Barnes & Noble, 1968.

5. Johnson, William. A Native Durbar, or Assembly. Digital image. Europe, India, and Asia- Photographs, Manuscripts, and Imprints. 1855-1862. Web. http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/eaa/id/757/rec/1

6. Keith, Arthur Berriedale, ed. Speeches & documents on Indian policy, 1750-1921. Vol. 1. H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1922. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=VQsDAAAAMAAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR5&dq=Speeches+and+Documents+on+Indian+Policy&ots=eLkGsbKBqa&sig=cg2Y5iyaYKfvL3qbPQg4XUBgFB0#v=onepage&q=Speeches%20and%20Documents%20on%20Indian%20Policy&f=false

7. Rosales, Francisco Arturo. Chicano!: The history of the Mexican American civil rights movement. Arte Público Press, 1996. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=qvGgsGBFQncC&oi=fnd&pg=PR9&dq=Chicano!+The+history+&ots=fXH5Wb9UpU&sig=4l06FY9mIjjOJynOYg_XvVAeU5E#v=onepage&q=Chicano!%20The%20history&f=false

8. Poinsett, Joel. “The Mexican Character.” The Mexico reader: History, culture, andpolitics (2002): 11-14. http://inside.sfuhs.org/dept/history/mexicoreader/Chapter7/poinsett.pdf

9. Briquet, Abel. Tipos Mexicanos. Indios Esatdo [sic] De Vera-Cruz. Digital image. Mexico- Photographs, Manuscripts, and Imprints. 1 Jan. 1875. Web. http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/mex/id/517/rec/12

10. Execution in Mexico. Digital image. Mexico- Photographs, Manuscripts, and Imprints. 1 Jan. 1910-1917. Web. http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/mex/id/301/rec/10

11. “Quotes Relating to Photography.” Quotes Relating to Photography. Web. 30 Apr. 2015. http://www.scienceandreason.net/photo/photquot.htm

Works Cited

Briquet, Abel. Tipos Mexicanos. Indios Esatdo [sic] De Vera-Cruz. Digital image. Mexico- Photographs, Manuscripts, and Imprints. 1 Jan. 1875. Web.

Curtis, Edmund, and Robert Brendan MacDowell, eds. Irish historical documents: 809-811. New York: Barnes & Noble, 1968.

Dictionary.com. Dictionary.com. Web. 30 Apr. 2015.

Execution in Mexico. Digital image. Mexico- Photographs, Manuscripts, and Imprints. 1 Jan. 1910-1917. Web.

Johnson, William. A Native Durbar, or Assembly. Digital image. Europe, India, and Asia- Photographs, Manuscripts, and Imprints. 1855-1862. Web.

Johnson, William. Brahmin Women of the Konken. Digital image. Europe, India, and Asia- Photographs, Manuscripts, and Imprints. 1 Jan. 1855-1862. Web.

Keith, Arthur Berriedale, ed. Speeches & documents on Indian policy, 1750-1921. Vol. 1. H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1922.

Poinsett, Joel. “The Mexican Character.” The Mexico reader: History, culture, andpolitics (2002): 11-14.

Rajan, Rajeswari Sunder. “After’Orientalism’: Colonialism and English Literary Studies in India.” Social Scientist (1986): 23-35.

Rosales, Francisco Arturo. Chicano!: The history of the Mexican American civil rights movement. Arte Público Press, 1996.

“Quotes Relating to Photography.” Quotes Relating to Photography. Web. 30 Apr. 2015.

Images

http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/eaa/id/729/rec/24

http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/eaa/id/757/rec/1

http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/mex/id/517/rec/12

http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/mex/id/301/rec/10