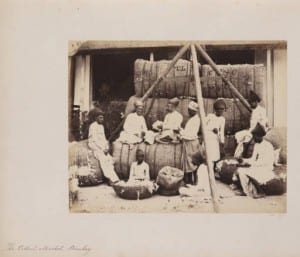

The Cotton Market, Bombay. Johnson, William. 1857.

They say a picture is worth a thousand words, but even those thousand words couldn’t begin to explain the importance of the picture above. Look at the surface of the photo and you’ll see Indian men and their cotton. Look deeper into the photo and you will see the lifeblood of the British Empire at its apex. India was the prized jewel of the British Empire, its value coming from the superior cotton grown and the lasting trade routes leading to trade centers all around the massive periphery of the wealth-obsessed British Crown. The wealth of the land was the reason the British did not surrender this land until over halfway through the twentieth century, but on the contrary, Indians went hundreds of years without freedom simply because they were able to master the art of growing cotton and making as much profit as possible through trade. While England thrived because of its most major colony, Spain did not have the same success when they took over the New World, mainly modern day Mexico and the American Southwest. After the gold and silver of the once great Mesoamerican tribes was all looted and sent back to Madrid, the profit of Spain’s lengthy conquest began diminishing. With all the value deep within the rocks in the form of rare minerals, and almost all of the available labor either dead or hateful toward the conquering nation, Spain began to realize that their method of spreading their empire may have not been the best in the long run. Instead of the rich, cotton traders of India, the faces of Mexican industry and trade differ immensely.

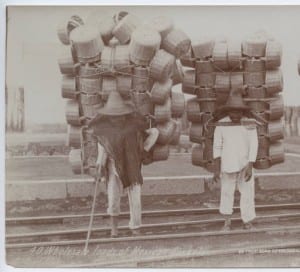

Wholesale Loads of Mexican Baskets. Waite, C.B. 1904.

After hundreds of years and dozens of superstition-led voyages toward the fool’s gold they were chasing after up north, Spain was in control of a massive amount of land with a small amount of natural wealth left. With poor political and economic order in the land so far from its empirical mother, the country began to fall out of Spain’s control. Eventually, the white, Christian/Catholic, Spaniards who had attempted to make Mexico the crown jewel of their empire had mostly all bred with the natives, losing their “racial purity” and their pure European ancestry. This new race of people born in the crucible of conquest claimed the country for themselves, with no resistance. Mexico ended up being more of a failure than a success for the Spanish, hence why they didn’t see the need to reclaim the country from the Mexican people who had claimed it as their own. The British Empire’s control of India was more prosperous and long-lived than Spain’s control of Mexico because of England’s emphasis on trade, starting at their first contact with the indigenous people. .

In 1497, the Portuguese explorer Vasco de Gama was the first man bold and brazen enough to round the horn of Africa in order to find a better way to get the spices and other eastern goods the wealth-oriented continent of Europe wanted. What he found was numerous large, well organized trading centers full of profitable goods accessible by boat. From that day on, India became the target of wealth seeking individuals. All across Europe, “all were drawn to India as a staging post in the wider eastern trade in spices and textiles. For the Mughals the British were but one of a range of useful trading partners and for this first century the relationship between Indians and Britons was a purely commercial one” (John 4). The British were quick to try to capitalize on the new land, and found what it was looking for in the Mughals. An already prosperous trade partner in the region, and initial contact being commercial in nature set the stage for what would become the British Raj. In 1857 the East India Trading Company of England essentially integrated itself into the already existing trade centers and set their own rules, all of which benefited the company and the crown. This trading company was so powerful and wealthy, that it altered the course of history. Emily Ericson notes that the East India Trading Company’s “success generated a tremendous amount of wealth, handed the British government the foundation of a global empire, and permanently altered the trade and economics of Britain and Asia” (Ericson 182). The Company, as it was known, gained its wealth through an intricate system of investment and trade. Once everything was in place in India, the Company worked its magic, making large profits in small amounts of time. In fact, “the import trade of the Company amounted, in the year 1814, from India and China to 6,298,386l. The declared value of imports of 1828, is 11,220,576l” (Thompson 17). The area of Bengal, which was part of the British Raj, saw even larger profits: “In 1784, the import from Bengal was 245,000 lbs. In 1828 it was 9,683,626 lbs,” (Thompson 18-19). The British East India Trading Company entered India with the goal of making profit; a goal they would instantly achieve and that would only increase their lust for more gold. Though technically a private company, the British government was heavily involved in the Company, especially when it saw opportunity. It wasn’t until 1857 that after an unsuccessful revolt known simply as the Indian Rebellion of 1857 that the British government officially began ruling over India. Indians, as is the case of most indigenous people of colonized lands, were treated unfairly and as second-class citizens to the British. A lack of nationalism because India wasn’t a nation, but rather an area with many city-states, combined with the fear left deep in the minds of the Indian people after witnessing the brutality of the British army while “subduing” the rebellion meant that none of the many calls of revolution were acted upon for nearly a hundred years. After 1857, the British did everything they could to retain India and milk as much profit out of it before the inevitable day when Indians would rule Indians, rather than the British. The complicated systems of financing and trading set in place by the British ensured profit, but also made sure all the profit was going to English, not Indians. So while men like these brokers toiled away, their hard work and sweat was turned into gold in the English treasuries.

Goojerattee Brokers. Johnson, William. 1857.

Lionel Abrahams was a member of the office in charge of commerce, and he “saw India’s London financial operations as a large waterway system comprising ‘rivers running into a lake at one side and so many rivers running out of the lake at the other side’. The goal of India Office (IO) officials like himself was to connect ‘incoming rivers with … outgoing rivers’, a task he acknowledged was ‘sometimes difficult’” (Sunderland 1). The rivers and lakes analogy shows the complexity of the whole system, with many inflows and many outflows. They used their nearly-perfected understanding of markets and business to ensure that wealth would return to England. Obviously the Indian people were not in favor of this kind of system, but Britain’s large standing military comprised almost entirely of Indians looking to make money while appeasing their rulers made sure any plans of armed rebellion remained nothing more than just plans. All the while, every good sold by the Indian’s was taxed and funded the then mighty British Empire. Some people involved in England’s Indian rule, including Company member T. Perronet Thompson, believed that the Indian people were the most important “object” available in India.

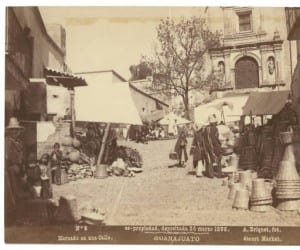

After seeing the Netherlands’ original success after finding a new route to the Indies, Spain made the investment of sending Christopher Columbus across the Atlantic in hopes of finding a quicker way to the goods they want and the wealth it would bring them. As we all know, Columbus failed at finding the non-existent route, but stumbled upon something even better, an entire continent yet to be exploited and drained of its wealth. After Columbus’ initial discovery, the gold-obsessed Spanish made it clear what their intentions were. “In the grants of the country, made to the first adventurers, the Spanish monarchs reserved one-fifth of the gold and silver that might be obtained, and for a considerable period the precious metals were the only objects that attracted attention, either in the colonies or Old Spain” (Niles 70). Knowing from Columbus that the indigenous people possessed precious stones and metals, like gold of course, Spain sent its Conquistadors to the New World to get as much of the gold as possible, then give a hefty chunk to the crown. America’s wealth was not truly realized until Cortez landed in modern day Mexico. He found the great, prosperous cities of the Aztec including the great capital of Tenochtitlan where he was greeted by the great emperor himself. Instead of following the Dutch and British protocol in India of integrating themselves into the already rich society, Cortez decided that kidnapping and assassinating the emperor then slaughtering his people was the best idea at the time. Superior weaponry and tactics meant Cortez returned home with most of his men and a bounty of gold, silver, and other riches looted from the instantly ruined city. Assuming there was much more to follow, the Spanish crown encouraged the exploration and settling of this new land. Coincidentally, the same people encouraging the exploration would still receive 1/5 of the bounty from the fruits of others’ labors. Once the great Mesoamerican cities of gold were stripped of their luster and glory, the only wealth left was deep underground in the form of minerals. With no locals to trade with, the Spaniards began exploring north to find more wealth, fueled by false, deceiving tales of wealth in the North from the understandably distrustful natives. The Spanish eventually wised up after being fooled one too many times, but it was too late to try to salvage the profitable opportunities that were squandered by the war mongers that first entered the lands. Still, the Spanish tried to the levels of wealth that seemed so promising after Cortez returned from the continent significantly wealthier than when he had left. Privately funded colonization to the modern-day American Southwest was one of the last major strides the Spanish took. However, like time and time before, “They were further discouraged when additional explorations failed to discover enough wealth to make the province attractive” (Chipman 60). Even further south, where agriculture, industry, and trade was beginning to pick up, Spain’s decisions proved to be fatal once again. Seeing the new world as inferior, Spain did not want to have to compete with New Spain in anyway. To make sure there was no competition, “several kinds of manufacturers were prohibited, which it was thought might prove detrimental to the mother country. The commercial restrictions imposed on the colonies were rigid and intolerable” (Niles 70). Spain shot itself in the foot yet another time. With little manufacturing, all that was left was agriculture and basic crafting. Unlike the great Indian Bazarrs, Mexico’s street markets were barren of anything of much value, only handmade baskets and other similar items as seen below.

Guanajuato Street Market. Briquet, Abel. 1890.

Spain chose war and plundering over trade, a decision that proved to be counteractive in their pursuit of profit. Lacking the steady stream of income through taxed trade, the large, dry heap of land full of irritated and sometimes violent natives became more of a liability than an asset. So, in 1821, Spain handed over the disorganized country over to the mixed-blood people who learned to call Mexico home.

The parallels between English ruled India and Spanish ruled America are obscured by the massively different styles of rule and the subsequent outcomes. Unbeknownst to then at the time, both the Company and Cortez set the fates of the new lands the ventured to since first contact with the indigenous. The British backed Company instantly found a trade partner in order to gain wealth, and focused majority of its long rule on trade and commerce. On the contrary, Cortez almost instantly turned to violence to gain wealth, and set the tradition of exploitation and violence that would be an ever too present part of the New World’s future. Simply said, the British prospered during their rule of India due to the well-organized systems of trade and commerce they began or improved upon, while the Spanish failed to recognize that a colony with no nurturing would return very little in terms of wealth.

Works Cited

Chipman, Donald E. Spanish Texas: 1519-1821. Austin: U of Texas, 1992. Print.

Erikson, Emily. Between Monopoly and Free Trade: The English East India Company, 1600-1757. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2014. Print.

John, Ian St. The Making of the Raj: India under the East India Company. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger, 2012. Print.

Niles, John M., and L. T. Pease. History of South America and Mexico: Comprising Their Discovery, Geography, Politics, Commerce and Revolutions. Hartford: H. Huntington, Jun., 1838. Print.

Sunderland, David. Financing the Raj: The City of London and Colonial India, 1858-1940. Woodbridge: Boydell, 2013. Print.

Thompson, T. Perronet. The Article on the Colonization and Commerce of British India. London: Republished by R. Heward, at the Office of the Westminister Review, 1830. Print.