This class has shed light on the fact that the two very different countries of India and Mexico have many similarities. From initial colonization, to castes systems, to revolutions, and more, studying India and Mexico in one class has made many connections never before thought possible from two countries on opposite sides of the planet. Although lectures and readings are important to make these connections, visual aids such as historical photographs are important to gather knowledge of these two empires. The people of these countries, especially the women, can be analyzed through photographs because “though undoubtedly a tool of perception, behind each photograph there is ‘not only a private eye, but layers of history as well’. In the process, as one views the photographs, one is also introduced to changing photographic techniques, women as ethnographic types, the importance of the studio and of backdrop, [and] the vibrancy of ‘action’ shots…” (Karlekar xi). Through visual analysis of historical photographs, the lives of working women in Mexico and India can be captured and examined. Aspects of these women’s lives include their job, caste system, and economic status.

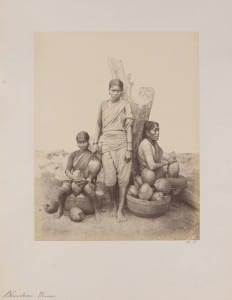

One theory about the origin of the caste system in India dates back to the beginning of class society and settled agriculture, and has existed ever since that time. A very important feature of the caste system is its control over women’s labor, for “caste not only determines social division of labour but also sexual division of labour. Certain tasks have to be performed by women while certain other tasks are meant for men. In agriculture for instance, women can engage themselves in water-regulation, transplanting, weeding, but not ploughing” (Desai 33). If not working in agriculture, women would work from the household, known as family-labor. The Indian women made a living from spinning and weaving, to milking cattle and selling butter, to marketing fruits and vegetables, like the women in the photograph below with their coconuts. They most likely make their living off of this produce, although it is evident that these women do not have high paying jobs. The level of dirtiness of their clothes and the simplicity of their clothes, which allowed for more physical mobility to produce manual labor, is evidence of their lower economic status. Absence of shoes also proves the inability of the women to belong to a higher caste. These Indian women are also very thin, demonstrating that they do not have an excess of money for food. Their caste does not allow them to have a more sufficient job to make more of a living. On the surface level, their jobs appear to be diverse, but when more research is conducted into the caste system, it can be seen that the job possibilities for women were in fact the opposite. Overall, subordination of women was justified by the caste system and divisions of labor.

do not have high paying jobs. The level of dirtiness of their clothes and the simplicity of their clothes, which allowed for more physical mobility to produce manual labor, is evidence of their lower economic status. Absence of shoes also proves the inability of the women to belong to a higher caste. These Indian women are also very thin, demonstrating that they do not have an excess of money for food. Their caste does not allow them to have a more sufficient job to make more of a living. On the surface level, their jobs appear to be diverse, but when more research is conducted into the caste system, it can be seen that the job possibilities for women were in fact the opposite. Overall, subordination of women was justified by the caste system and divisions of labor.

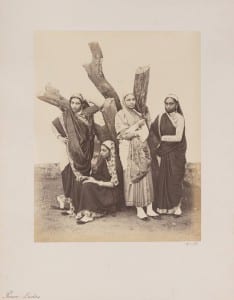

In modern day, the way one dresses is important. The emphasis on appearance was just as present in the early nineteenth century. As stated by Karlekar, “Dressing for the occasion was often important as clothes and other accoutrements were vital props in the spectacle of presenting oneself for an audience” (xiv). With the use of photography for showcasing oneself on the rise, outfits for these photoshoots were crucial to those at the time. The Parsi gara or garo, a sari with Chinese embroidery in white or a variety of colored threads, was introduced to India in the latter part of the nineteenth century. Brought back to the country by Parsi traders in the 1850s, the colorfully embroidered borders of butterflies and peonies soon became a popular style and spread throughout India and, “by the latter part of the nineteenth century, the Parsi gara or garo became increasingly popular among the westernized elite of the Bombay and Bengal Presidencies” (Karlekar xiv). Although one general style prevailed at the time, women took initiative in changing the dress slightly based on location. Women on the west coast and northern India draped the sari pallav over their right shoulder, while women in Bengal started to drape the cloth over the left shoulder. Therefore, it can be seen and deduced that the women in the photo are from either the west coast or northern part of India because of the way they drape the sari. These women also complete the dress of western elite females by wearing closed shoes and ornamenting themselves with one earring, while the other ear is firmly placed behind the mathubanu, or head binding over the sari pallav. Although the spread of the Parsi gara or garo expanded to women across the nation, it is apparent that these women are of a higher caste. The four women pictured have enough wealth to have the beautiful and detailed gara or garo, closed shoes, and jewelry, including bangles, earrings, and rings, proving that they do not complete manual labor to survive. Related, it is important to note the visible health of these women, as it looks as though they have enough nutritious food to eat. The caste of these women provides a higher quality of life for them, and perhaps it can be deduced that the women in the photograph do not need to work at all because of their caste. The economic status, caste, and job, or lack thereof, of these women is seen in the photograph alone.

These women also complete the dress of western elite females by wearing closed shoes and ornamenting themselves with one earring, while the other ear is firmly placed behind the mathubanu, or head binding over the sari pallav. Although the spread of the Parsi gara or garo expanded to women across the nation, it is apparent that these women are of a higher caste. The four women pictured have enough wealth to have the beautiful and detailed gara or garo, closed shoes, and jewelry, including bangles, earrings, and rings, proving that they do not complete manual labor to survive. Related, it is important to note the visible health of these women, as it looks as though they have enough nutritious food to eat. The caste of these women provides a higher quality of life for them, and perhaps it can be deduced that the women in the photograph do not need to work at all because of their caste. The economic status, caste, and job, or lack thereof, of these women is seen in the photograph alone.

During this same time on the other side of the world, life in Mexico was difficult for all, but more so for women. During and after the Mexican revolution of 1910-1920, Mexicans immigrated to the United States in search of better opportunities. The chaos from the revolution, along with intense poverty in most of the country, motivated Mexicans to make the move. Their dreams included earning enough money to support themselves and their families to provide improved qualities of life. Location was important for them, therefore, “they chose the Southwest because it was accessible; because, having once been part of Mexico, it would be more like home, and because they hoped to fit in easily in a society which already had a large Mexican-American element” (Samora 132). However, most Mexicans knew little besides farming, unaided by their low levels of education. The skilled farmers quickly filled the available jobs in agriculture that paid them low wages, similar to the system in Mexico that they were trying to escape. Many Mexicans lacked money and ranchers were vulnerable to market downturns and unstable weather, so in response, “some sold out to pay taxes while other ranchers subdivided their land among heirs until no parcel remained large enough to support their families” (McKenzie 59). Many Mexican Texans, also known as Tejanos, faced levels of poverty and struggled to feed and clothe their families. But not matter the struggle these people faced, Mexican Texan women continued to serve their traditional foods in this new land, including corn tortillas, tamales, frijoles (beans), chiles, cabrito (kid goat), and nopalitos (cactus leaves).

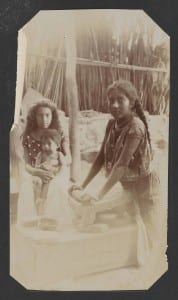

These Mexican Texan families lived in simple houses built of materials gathered from the land. In wetter areas, rain would return the traditional adobe (mud and straw brick) huts into mud. Poor Tejanos lived in “jacales”. A jacal is a hut made from readily available materials to that area, such as mesquite posts. Jacales were built by laying the logs side by side and chinking the spaces in between the boards with mud. These huts would have a peaked roof frame above the walls, thatched with local grasses. Most jacals had packed dirt floors and were vulnerable to insects and bad weather. Most Mexican Texans grew their own food close to their homes, including corn, peppers, beans, tomatoes, and squash. Improving ones quality of life was hard in Mexico and the American Southwest for many reasons, but one profound aspect of life at this time was that, “Some counties prohibited Mexican children from attending school beyond sixth grade” (McKenzie 75). That fact alone means that the children in this photo could already be prohibited from attending school. The poverty that these children live in is evident through their clothing (plain and dirty) and their environment (which appears to be a jacal, with log walls and dirt floors). One of the children is also grinding corn, which is a traditional and cheap food that is easily grown in personal gardens, helping to prove the lower economic status of these children. These children are “working” to help take care of their family, by watching over the younger siblings and preparing food, instead of improving their lives, economic status, and caste by attending school. The disparity of Mexico and the American Southwest previously described is evident in this photo, with females as the main subjects.

The poverty that these children live in is evident through their clothing (plain and dirty) and their environment (which appears to be a jacal, with log walls and dirt floors). One of the children is also grinding corn, which is a traditional and cheap food that is easily grown in personal gardens, helping to prove the lower economic status of these children. These children are “working” to help take care of their family, by watching over the younger siblings and preparing food, instead of improving their lives, economic status, and caste by attending school. The disparity of Mexico and the American Southwest previously described is evident in this photo, with females as the main subjects.

Mexico has many agricultural products in different areas of the country. But one of these products is highly revolved and driven by the female population, and that is coffee. The Mexican state of Veracruz has more coffee workers and grows more coffee than any other state in Mexico. For the last 150 years, the coffee industry created employment for thousands of working Mexican women and fostered development and unionization of a working women’s culture, but, “working women’s culture can be quite distinct from that of working men’s culture” (Fowler-Salamini 10). As the merchants, preparers, and exporters of the product, women had an important role in stimulating the development of Latin American coffee-export economies. Although coffee remained Mexico’s second most important agricultural export for many decades, the country also had other more lucrative exports, including cotton, sugarcane, and minerals, that obtained more attention and importance. The state of Veracruz and its coffee economies were primarily concentrated in five highland towns, being Xalapa, Huatusco, Orizaba, Córdoba, and Coatepec. While studies on the predominantly female labor force of the coffee industry are scarce, the essential and important role of women as coffee sorters, cleaners, and exporters, or escogedoras or desmanchadoras, never went unnoticed. Although working in the coffee industry was linked to manual, low-paying, and less prestigious work, the women themselves never bothered to think of this, as they were able to earn steady seasonal wages and join the public workplace. In the 1920’s, standards of labor in the coffee industry were changing for the better for both men and women. However, “women workers were increasingly marginalized by the men-dominated national trade union movements allied with the officially party that were determined to impose their control over their memberships” (9).

Despite the power the men thought they had, women dominated the coffee sorting aspect of the coffee industry, and created some autonomy in the union and developed leadership positions, not linked to their masculine counterparts. The following photograph was taken in Coatepec in 1904. It shows people sorting coffee, with four out of the six people in the photograph being women. Although these women were considered lower caste citizens because of their profession, they seem healthy, clean, and satisfied that they have a source of income. In addition, through their profession, the Mexican women have a bond and strength in numbers that came solely from the industry. This photograph provides a historical picture of women at their job, improving their economic status, and living through their caste.

Bringing together two very seemingly different cultures can be a difficult task. But the similarities between India and Mexico are more abundant than one would think. Finding these similarities can be accomplished through research in typical textual sources. But visual mediums such as historical photographs are also very useful when learning about people of the past in their empires of the time. Analysis of photographs of working women in both India and Mexico concluded ideas about jobs, different caste systems, and one’s economic status. Throughout history, women have been disrespected and lowered to less desirable standards by men and their societies simply because of their gender. These photographs prove that women worked just as hard as men, if not harder, to make a better life for themselves. No matter the job, or what caste they were in, women always pushed through their struggles. When looking at photographs, or life in general, the saying goes, “beauty is in the eye of the beholder”, and throughout history, women have made it more beautiful.

Bibliography

Desai, Neera, and Maithreyi Krishnaraj. Women and Society in India. Delhi: Ajanta Publications (India), 1987. Print.

Fowler-Salamini, Heather. Working Women, Entrepreneurs, and the Mexican Revolution: The Coffee Culture of Córdoba, Veracruz. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2013. Print.

Karlekar, Malavika. Visualizing Indian Women 1875-1947. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2006. Print.

McKenzie, Phyllis. The Mexican Texans. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2004. Print.

Samora, Julian, and Patricia Vandel Simon. A History of the Mexican American People. Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 1977. Print.

http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/mex/id/2574/rec/3

http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/mex/id/243/rec/87

http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/eaa/id/670/rec/39

http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/eaa/id/747/rec/62