What do India and Mexico have in common? On the surface, the similarities are not striking. However, digging deeper into the layers of history reveals a much broader insight into the legacies left behind on these two countries by the colonial-era empires of both Britain and Spain. History books and written primary sources layout a framework for analyzing certain concepts and trends, such as culture, gender, infrastructure, and the military. Photographs, on the other hand, place these concepts in a visual context. They allow us to see the integration of ideas in societies of the past. Historical photographs of India and Mexico exhibit the socio-cultural awakening that took place at the height of nineteenth century European colonialism through depictions of religious and social reform, gender and familial roles, and industrial revolution.

The extensive transformation of social institutions under British colonial rule is one of the many unfaltering themes of India’s history. European expansionism, throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, was fueled by a hunger for land, power, and natural resources, and involved little concern for the welfare of anyone who stood in the way of the growing empires. Europeans entered into already populated regions, such as India and the Americas, and imposed their lifestyles onto civilizations they deemed inferior. The perception of India as a subordinate nation stems from British ideas of the “orient” that shaped how race and gender were recognized and used to assert power over the Indians. These preconceived notions of the native Indian people greatly contributed to the tensions that would later ensue. Sir George Clerk, a nineteenth century administrator, noted: “There are two modes of governing India—with the people, or without the people” (Peers 17). The British had no desire to govern with the people of India, and thus allowed “the social and cultural gap [to remain] wide” (ibid). In order to strengthen their hold, British officials implemented a caste system as a more effective means of organization, rather than directly ruling the Indian people. At this point in time, the caste system was considered “India’s most important social [institution],” along with its “archaic and dominating forms of religious community” (O’Hanlon 100). The interactions between the Caste members and colonial rulers resulted in the establishment of new scribal and commercial elites, and the consolidation of social authority and political power (ibid).

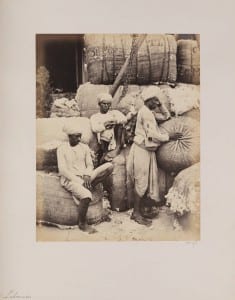

The main caste system, known as the Varna, could be traced back to the original Veda scriptures of the Hindu religion (Stead). The Varna consists of four ranks, starting with Brahmins at the top, following with the Kshatriyas, the Vaishyas, and finally the Shudras. Before British rule, the Varna was simply a method of dividing the traditional Hindu population by social responsibilities. The caste system as we know it today, however, reflects the British appropriation of inherently Hindu systems and practices (Milner). Colonial rulers were quick to capitalize on an existing structure in order to enforce the separation of people by wealth, power, and even occupations. The four Varnas no longer held the same meanings. For example, the Kshatriyas were originally purposed to protect society in times of war, and govern in times of peace (Oon). These people who once held the role of serving humanity, were now expected to engage in mercantile operations in order to fulfill the political and economic demands of the British (ibid). The Lohana people, a subset of the Kshatriyas, are known as members of the urban Hindu mercantile community (Majumdar, 210). Despite the British considering the Kshatriya to be the second highest caste after the Brahmin, their physical appearance does not reflect that. The Lohana men, photographed by William Johnson in 1860, appear to be wearing simple, unadorned cloths that are similar to those of lower-caste Indians, who took on the more labor-intensive jobs such as working in the fields. Even with the deep-rooted Hindu traditions of the Varna, jobs were strictly regulated among the different classes. As the demand for cotton textiles extended throughout the world, the British saw this phenomenon as an opportunity to benefit financially from the Indian economy and its notoriously cheap labor. Both social and economic reformation reached new heights as Britain pushed for sedentarization and industrialization in India concurrently (O’Hanlon, Colonialism and Social Identities in Flux). This campaign by the British transformed what was once a mobile agrarian society, to stationary, and encouraged the development of factories to expand the cotton industry to major cities such as Bombay and Calcutta. The interactions between the Caste members and colonial rulers resulted in the establishment of new scribal and commercial elites, and the consolidation of social authority and political power (O’Hanlon). Industrialization in India, while it was slower than in Europe, sparked more rapid urbanization in the major cities, and the emergence of a new middle class to keep up with the demands of production. In order to meet the needs of their growing empire, the British found it necessary to completely alter social organization, such as converting the Lohanas from warriors to merchants.

The Kshatriya Lohanas are just one of many subgroups whose roles in society were changed by the British reconstruction of the caste system. In fact, when the British Empire abolished slavery in 1833, they lost the manual labor that the slaves once provided (Zgoda). To make up for the shortage of manpower, Colonial rulers made indentured servants out of the lower-caste Indians (ibid). As there were very few opportunities for the uneducated, and now unemployed, Indians to find work, indentured servitude seemed like an ideal job, especially because it provided food and housing (ibid). Many indentured servants later realized the poor quality of life of such a profession, however they were already bound by contract and could not escape the inadequate living conditions. The photograph titled, Ghatee Hamalls, or Bearers, was taken around the 1850s or 1860s by William Johnson, and displays six men outside a building. In the center of the photograph, there is a British man who appears to be lounging in a raised-up compartment, and is talking with a well dressed, middle class Indian man. Four additional Indian men, who are wearing nothing but pieces of cloth, are holding up the compartment. Their actions and lack of suitable clothing suggest that they are of significantly lower class than the other two men. Given that Bearers is the title of the photograph, it is safe to assume that these four men are the bearers, or the male servants, of the wealthy British man that they are tending to. This photograph provides visual insight to the poor working conditions that indentured servants were bound to under the British rule, while also representing two, maybe even three, of the class levels that were prominent in 19th century India.

In the first half of the 19th century, Mexico lacked the people, power, and resources it needed to keep up with the economic and industrial advancements of adjacent nations, and to stand out against their dominating presences. Mexico’s inability to grow left it stuck under the capitalist system, while the United States moved towards industrialization from a more agriculturally based system (Hall). While the United States moved forward with the rest of the world, it almost seemed as if Mexico was moving backward. However, Spain saw Mexico’s challenges as an opportunity for their own economic interests to flourish. It was this intervention by the Spanish that acted as a catalyst in the transformation of the social order within Mexico. The drive for American expansion into the Southwest collided with Mexico’s arising internal conflicts and disruption of social organization. According to Thomas D. Hall, there were several ways “in which Mexican conditions contributed to the 1846 conflict.” He stated that, “globally, there were specific and systematic factors in the Spanish Empire that contributed to… the circumstances of Mexican Independence,” and that “nationally, there were changes in foreign investment, economic development, and the turbulent internal political conditions that lasted from the Hidalgo rebelling in 1810 through the consolidation of power under Porfirio Diaz in 1876” (Hall). Internally, Mexico struggled with a “chaotic government,” that failed to meet the demands of the now industrialized global economy, and cited “transportation costs as one of the two major obstacles to Mexican economic growth in the nineteenth century” (Hall). Mexico’s eventual separation from Spain and newfound economic dependence on Britain led to the introduction of the feudal system, which caused even more instability, especially among the Mexican social classes. Mexico’s complex history and ongoing internal struggles with power and order allowed stronger colonial rulers to assert control over the failing nation.

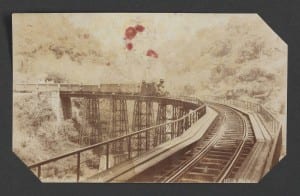

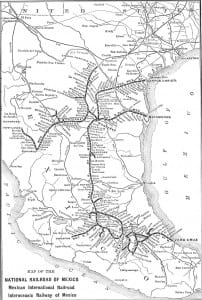

The introduction and expansion of railroad development in the nineteenth century brought about the rapid economic growth that Mexico was looking for (Coatsworth). While the living conditions for the Mexican working class were anything but ideal, the railways greatly impacted the agrarian communities, as well as benefitting the wealthy upper class (Van Hoy). Teresa Van Hoy stated that, “Railroad officials sought to gain access to local resources such as land, water, construction materials, labor, customer patronage, and political favors. Residents, in turn, maneuvered to maximize their gains from the wages, contracts, free passes, surplus materials, and services (including piped water) controlled by the railroad. Those areas of Mexico suffering poverty and isolation attracted public investment and infrastructure” (Van Hoy, Preface). The photographs of the Metlac Bridge and Locomotive on Mexican-Vera Cruz Ry, taken by C.B. Waite in 1902 mark a great triumph in Mexico’s eventual move towards industrialization. As Van Hoy presented in her book, A Social History of Mexico’s Railroads: Peons, Prisoners, and Priests, and as seen on the map of Mexico’s railway system, trains connected people from all over the country, and enhanced the spread of goods and ideas.

Without photographs, we are forced to rely on written and verbal accounts of the past that have been transferred from person to person, and often altered along the way. Yes, it is absolutely possible that many of these historical photographs were staged even in the earliest days of photography; however, historians are obligated to consult many different mediums when conveying the most accurate truth about the past. Looking at history through different lenses opens the floor to alternative perspectives, ideas, and conversations about civilizations before us. The historical photographs of India and Mexico provide us with unique visual insight to the impact of European expansionism and colonialism on the nineteenth century world.

Works Cited and Referenced

Alonso, Ana Mari. Thread of Blood: Colonialism, Revolution, and Gender on Mexico‘s Northern Frontier. Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press, 1995.

Andrabi, Tahir and Michael Kuehlwein. “Railways and Price Convergence in British India.” The Journal of Economic History Vol. 70 (2010): 351-377.

Bogart, Dan. “Nationalizations and the Development of Transport Systems: Cross-Country Evidence from Railroad Networks, 1860–1912.where da white wimmin at” The Journal of Economic History. Vol. 69, No.1 (Mar., 2009), pp. 202-237.

Coatsworth, John. “Indispensable Railroads in a Backward Economy: The Case of Mexico.” JSTOR. December 1, 1979

Cuellar, A. B. “Railroad Problems of Mexico.” Annals of The American Academy of Political and Social Science 187 (1936): 193-206. doi:10.1177/000271623618700128

Stead, Estelle. The Caste System in India: The Review of Reviews (1918): 423

Ficker, Sandra Kuntz. “The Export Boom of the Mexican Revolution: Characteristics and Contributing Factors.” JSTOR. Cambridge University Press, Web. 07 Apr. 2015.

Gauss, Susan. “Made in Mexico: Regions, Nation, and the State in the Rise of Mexican Industrialism, 1920s-1940.” The Hispanic American Historical Review Vol. 92 (2012): 574-575.

Glick, Edward B. “The Tehuantepec Railroad: Mexico’s White Elephant”. Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 22, No. 4 (1953): pp. 373-382. JStor.org (accessed April 07, 2015).

Tinker, A New System of Slavery: The Export of Indian Labour Overseas 1820-1920, Oxford University Press, London, 1974

Hall, Thomas D. The Sources of the American Conquest of the Southwest. 167-181.

Hardy, Osgood. “The Revolution and the Railroads of Mexico”. Pacific Historical Review, Vol. 3, No. 3 (Sep., 1934): pp. 249-269. JStor.org (accessed April 07, 2015).

Majumdar, Maya. Encyclopaedia of Gender Equality Through Women Empowerment. New Delhi: Sarup & Sons, 2005. Print.

Milner, Murray, Jr. “Hindu Eschatology and the Indian Caste System: An Example of Structural Reversal.” Journal of Asian Studies 52, no. 2 (May 1993): 298-319. Accessed April 7, 2015.

O’Hanlon, Rosalind. A Comparison Between Women and Men: Tarabai Shinde and the critique of gender relations in colonial India. Madras: Oxford University Press, 1994.

O’Hanlon, Rosalind. Colonialism and Social Identities in Flux: Class, Caste, and Religious Community. Peers and Gooptu. Oxford University Press, 2012.

Oonk, Gijsbert. “The Changing Culture of the Hindu Lohana Community.” Contemporary South Asia. Carfax, 1 Mar. 2004. Web. <http://www.sikh-heritage.co.uk/heritage/sikhhert EAfrica/nostalgic EA/Changing_Culture.pdf>.

Peers, Douglas M., and Nandini Gooptu, eds. India and the British Empire. Oxford University Press, 2012.

Pletcher, David. “The Building of the Mexican Railway.” The Hispanic American Historical Review Vol. 30 (1950): 26-62

Van Hoy, Teresa. “A Social History of Mexico’s Railroads: Peons, Prisoners, and Priests (review).” The Americas 66.2 (2009): 297-298. Project MUSE.

Zgoda, Mason. “History of Indentured Servitude Between the 18th and 19th Centuries.” HubPages. HubPages, 3 Mar. 2013. Web. <http://masonzgoda.hubpages.com/hub/History-of-Indentured-Servitude-Between-the-18th-and-19th-Centuries>.