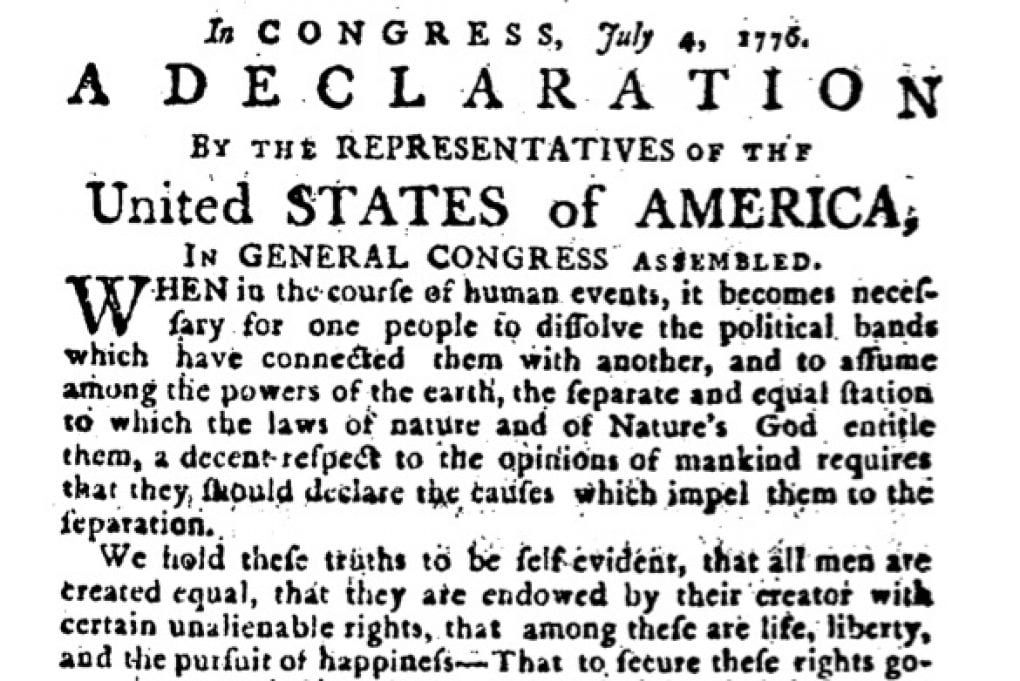

The Declaration of Independence as it appeared in the Pennsylvania Gazette, July 10, 1776

“The United States was founded for religious freedom!” This statement, heard from countless students and politicians over the years, suggests that the religion of the generations that lived through the founding era are of enduring importance to the nation. Yet what was the religion of the period? The evidence is confusing. Americans were not members of a single church or denomination. The most influential political leaders, those we remember as the Founding Fathers, were not representative of the general population. The religious freedom embodied in the First Amendment did not become law until the very end of the period, in 1791. And which part of the American Revolution matters most to this subject? Is it the decision to break with Great Britain in the 1770s? Or the process of becoming a stable nation more than a decade later?

To answer these questions, a group of students from SMU spent the semester digging into the newspapers. They chose topics that revolved around religion — sometimes because the word “religion” appeared in the article, sometimes because the subject connected to religion in another way. Persistently, students returned to slavery during the nation’s founding as an important moral topic. We discussed it in class, and they researched it independently. All the students spent weeks transcribing and analyzing their articles, and each student produced a blog post and data visualization.

The answers present a wide range of insights on the subject. Religion, as it appeared in the newspapers, was often political, but it also appeared in other contexts, including literary. Colonists connected it to ideas like liberty and freedom. Anti-Catholicism, a key part of British political culture in the mid-eighteenth century, resonated in the colonies too. But if religion was political, was it also, well, religious? One student found that religious leaders were notably absent from discussions; another that clergy did not use the newspapers to try to build a pious population. In another great pairing, one student found that Native Americans were depicted as savage, while another found the religiously-charged word “heathen.”

Raising the question of happened in the newspapers, and what did not, is an essential part of this project. A few words on method are useful here. The class used Readex’s American Historical Newspapers collection, and searches were confined to the period of 1763-1789, through Readex’s search apparatus. This research method requires two important caveats about the results.

First, subjects that were not printed in the press did not appear. Certainly, a vast amount of material related to the founding era, including sermons and other forms of print culture, were not a part of the project. As several students noted, newspapers are biased towards matters that are urgent and pressing, demanding immediate action. Of course, revolutions, as times of crisis, are also times of urgent and pressing concerns. In addition, newspapers were more often in urban places, and cities were more often in the northern colonies.

Second, Readex’s search engine is based on OCR rendering of eighteenth-century type. As many scholars have documented, this process is very difficult and prone to a very high number of errors. Students transcribed the articles to ensure that their analysis of the articles they found was accurate. Finding the articles, however, remained dependent on a highly imperfect OCR. The methods offered by distant reading and digital humanities offer many new opportunities, and they are worth pursuing. As with any method, they also offer new and persistent challenges.

Those caveats do not, I believe, change the fact that the students have provided a well-rounded way to enter the subject of religion and the American Revolution. There is no one answer, only myriad ways to enter the question. We looked for deists and revivals, at battles, heroes, and villains, moments of controversy and places where the action might be found. Although I have done some broad analysis of the themes in the body of sources the students collected, I will refrain from drawing any summary conclusions, because I believe the real wisdom in what the students have found is in its nuance and diversity. Religion was everywhere in the American Revolution, but it was nowhere quite what we expect.

Please explore the students’ findings. For a different perspective on how religion shaped the founding era, through its founding documents, please see this site.

Kate Carte Engel, Associate Professor of History, SMU