By Adam Sanchez

Benedict Arnold. If you know anything about him, his very name brings a slight cringe to your mind. What do we know of the man? Why exactly did that cringe come to your mind?

He was an outstanding leader in the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War, one of General George Washington’s top men. Arnold was, without a doubt, a fervent patriot, being attributed with leading the American forces to victory at the Battle of Saratoga, a critical engagement with substantial implications on the international politics of the war. Benedict Arnold also decided that he would switch his allegiances from the Continental Army to the British Crown and surrender the American fort at West Point, in exchange for £20,000 and the appointment to Brigadier General in the British Army. In his service with the British, Arnold captured Richmond and, a few months later, razed the town of New London.

I can hear the more patriotic readers screaming “Traitor!!!” in their minds (and maybe even out loud!). Traditional American history has taught, for the past two centuries, that Benedict Arnold betrayed America and sold out to the King of England, since becoming one the most infamous actors in American history: George Washington’s golden boy turned malevolent turncoat. What a story! Such drama!

The majority of newspapers at the time would also certainly agree that Benedict Arnold was a slimy character at best. This word visualization, taken from a list of twenty five select articles ranging from 1780 to 1786, attests to this with words like infamous, traitor, devil, enemy, treason, falsehood, and robbed. Upon an extremely cursory glance at those words, we can surmise that the people Arnold betrayed didn’t particularly like him (shocker, right?!).

Nothing surprising there. Going into the research, I expected to find corrosive language describing him. After all, traditional American history has brought up little else in regards to the man that was Benedict Arnold. Historical newspapers mirror that trend. The most obvious word that appears in the visualization, however, is country, and that was something that caught me off guard and that I would like to bring to your attention. Its size is indicative of its relative frequency within the body of texts; meaning that after sorting out common words, it is highly prevalent.

I will make two observations in regards to the appearance of the word country, both with ENTIRELY different implications, both revealing different facets of Benedict Arnold’s story that are not part of traditional American history’s retelling. This is where the title of the post becomes immediately relevant: Benedict Arnold and His Country. I will define “His Country” in two ways: 1) as the country belonging to Benedict Arnold, and then 2) as the country belonging to God, the entity referred to with capitalized pronouns. A double entendre.

My research led me to primary sources that lent credence to the possibility that Benedict Arnold, contrary to everything you’ve been taught, loved his home and his country, the thirteen colonies, so much so that he could not bear to be a part of their demise (“Blasphemy!”). In two separate letters he wrote, one written to George Washington and the other addressed “To the Inhabitants of America”, Arnold explained his motives behind his seemingly treacherous actions. Writing to Washington, he clarified: “I have ever acted from a principle of love to my country, since the commencement of the present unhappy contest between Great Britain and the Colonies: the same principle of love to my country actuates my present conduct, however it may appear inconsistent to the world…” Arnold wrote with a sense of sincerity that really makes you want to pity his situation. To the modern reader, as well as to the colonial one, Arnold made bold statements, none of which seem to match up with his actions at West Point. Claiming to love the country he sold out!! Either Arnold was a remorseless bald-faced liar OR he truly and deeply loved his country. There is little room for gray-area. He finished his letter with: “I have the honor to be, With great regard and esteem, Your Excellency’s most obedient Humble servant, B. ARNOLD. His Excellency, General Washington.”

This coming from the man who wanted to surrender an American fort to the British Army… the audacity!

Or perhaps the unflinching determination to keep his country alive. A patriot that had seen his homeland stray from the path, and was willing to risk everything to bring it back to true liberty and true freedom. In another letter, entitled “To the Inhabitants of America”, Arnold wrote that he joined the fight for American independence because the rights of his country were in danger and his duty called him to its defense, but that the American alliance with the French would be its ultimate demise. He could not in good conscience follow “the enemy of the Protestant Faith…, fraudulently avowing an affection for the liberties of mankind, while she holds her native sons in vassalage and chains.” Benedict Arnold claimed to have been even more of a freedom-loving patriot than his counterparts were! He was totally unwilling to give his liberty to the enemy of freedom (in his mind the French) in the hope that he might gain it from the British. Arnold could not stand to watch the nation he so loved, essentially free itself from one set of shackles, only to immediately commend itself into the insidious hands of the French. How noble!

On the other hand, let’s talk about His Country: America in relation to God, from the Protestant Christian viewpoint. He was everywhere. Whether they believed in Him or not, God was on the minds of the people of the revolutionary American era. Heck, the first sentence of the Declaration of Independence references the guy, and the first amendment of the Bill of Rights mentions the freedom to practice religion. God seemed to permeate past the places He was supposed to stay in: the bible, churches, Sundays, preachers, etc. The word cloud, taken from articles with the mention of Benedict Arnold, does not just reflect the political and military pieces of the story with words like army, commander, congress, country, and America, British, but it also reflects the moral values held by the colonists with devil, infamous, traitor, treason, robbed, crimes, and falsehood. I began to get the sense that the lines between religion and politics were very blurred, which was only affirmed by the empirical findings of the word cloud.

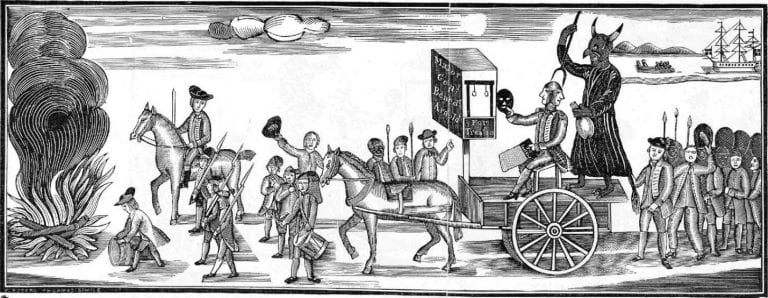

I found that these newspapers were actually the place where religion and politics slammed together, and how fascinating it was to analyze! Benedict Arnold, going by the facts, was purely a political and military actor. His actions in the Revolutionary War had as much to do with religion, as Donald Trump has to do with political correctness. Nada (Unless I’m missing a very subtle link…). HOWEVER, I found that often enough, Arnold was portrayed in the sense that he was evil!

The above cartoon came up in several newspapers in Philadelphia and Boston: “the Devil, dressed in black robes, shaking a purse of money at the General’s left ear, and in his right hand a pitch fork, ready to drive him into hell as the reward due for the many crimes which his thrift of gold had made him commit.” The reasoning for placing Arnold in such a religiously charged position is because of his relationship with the country and its quest for freedom. The colonists viewed their quest for freedom as holy and providential, and that the “popish” English government (a title that has no actual basis, other than Catholicism being mentally linked to tyranny) was inherently evil, solely due to the fact that it was opposed to the colonists’ quest for freedom. Thus, from the perspective of the colonies, the religious and political realms collided, resulting in a basic formula:

(Disclaimer: I’m a history major, so my math might be a little off) The colonists linked their views of God and religion with their views of politics, regardless of actual correlation. Here’s the quick guide: Whatever the colonies wanted became good, and because they wanted what was good, the colonies had God on their side, because God wanted what was good. If you’re looking at the screen with one eyebrow raised and your mouth open just wide enough to exemplify the perfect amount of confusion, no worries, you are in good company!

But let’s continue with this line of thinking. England was opposed to the colonies having freedom, therefore the English became inherently tyrannical, traitors to the rights of man, evil, and (probably…) the same as Satan! Oh my, the ease of living in a world where there was so clearly a right and a wrong side!! Said no enlightened person ever. The country that Benedict Arnold lived in (and betrayed) was a country that was heavily influenced by its Christian roots, as seen in the country’s view on moral evils, its founding documents, and its demonization of Arnold. I’m not here with the answers to why; I’m here pointing out an intriguing trend of late 18th century America

As it turns out, there was more to Benedict Arnold’s story than the fact that he was a two-faced traitor that hated America (History books are kind of biased sometimes, you know?). Arnold may have actually loved his country. And that country totally demonized him because it viewed his defection to the British as a sin directly against God. These are the observations of a nineteen year old college student from Texas looking at a group of words with varying sizes, colors, and orientations.

Further Reading

Boylan, Brian Richard. Benedict Arnold: The Dark Eagle. New York: Norton, 1973. Print.

Cole, Darrell. “Whether Spies Too Can Be Saved.” Journal of Religious Ethics J Religious Ethics 36.1 (2008): 125-54.

Martin, James Kirby. Benedict Arnold, Revolutionary Hero: An American Warrior Reconsidered. New York: New York UP, 1997.

Randall, Willard Sterne. Benedict Arnold: Patriot and Traitor. New York: Morrow, 1990.

Wilson, Barry. Benedict Arnold: A Traitor in Our Midst. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s UP, 2001.

Comments are closed.