Nestled within the cosmopolitan Dallas, Texas, lies a temple devoted to Krishna, a Hindu deity. The temple is a bastion of the ISKCON (International Society for Krishna Consciousness) faith, a place for devotees of Krishna to gather and practice. The Hare Krishna Movement, as it is known, stretches back not thousands of years—as base Hinduism does—but decades, to 1966 in New York. A. C. Bhaktivedanta, later referred to as the Swami Prabhupada, was an Indian native that came to the US to speak of Krishna and devotion to him. From there, the movement spread across the globe, becoming an international faith system in more than name.

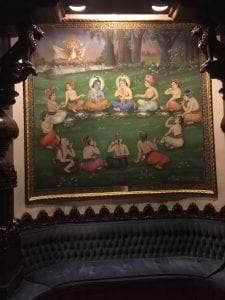

Popular conception of the Hare Krishna movement and adherents stands in stark contrast to the experience of an actual temple. The organization and religion is oft portrayed as consisting of young “New York hippies,” with the various connotations of hallucinogenics and frivolity that follow such a label (Hopkins 172). They are said to storm public spaces, banging loud drums and chanting about Krishna, depictions that stem from the movement’s beginnings when such instances actually occurred. The reality today in Dallas, however, is a much different story, with the temple’s members consisting predominantly of immigrant Indian families. The temple is a place where all ages, from the elderly to children, come together as a community to partake in communal rituals that uphold Krishna. They engage their senses, waving hot flames near their skin and bringing freshly cut flowers to their noses. They surround themselves with images of Krishna and his various acts, beautiful paintings that show how Krishna is engaging with them in turn. They are not frivolous individuals coming together as an excuse to party, but are devout believers actively practicing their faith. They hold puja, or service, throughout the entirety of the day, starting as early as 4 A.M., dress the idols of Krishna in new clothes daily, and hold classes on the philosophy of Hinduism and the Swami Prabhupada’s teachings. There were no attitudes “contemptuous of women,” an image that came into being when Swami Prabhupada died and his sannyasi preachers took over (Hopkins 184). Men and women stood side by side, chanting together, and a little girl brought flower buds around for practitioners to smell. Everyone took part and was encouraged to partake and act as a singular unit.

Prior to visiting the temple, I held the misconception that the Hare Krishna movement consisted of a Western, voyeuristic appropriation of foreign beliefs for the sole purpose of being counterculture . It was a byproduct of how popular culture portrays the faith. It was surprising—in a good sense—to see that such was not the case. Prajapati, our tour guide, was the only white member during our visit and truly seemed to believe everything he was telling us. He took his beliefs seriously and was overjoyed at the opportunity to share a piece of it with us, an attitude shared with the rest of the practitioners present.

Hopkins, Thomas J. “ISKCON’s Search For Self-Identity: Reflections by a Historian of Religions.” The Hare Krishna Movement: Forty Years of Chant and Change, edited by Graham Dwyer and Richard J. Cole, 2007, pp. 171-192