Terracotta Bull Figurine

About 2600 – 1900 BC

The Indus Valley – Harappa, Pakistan

The British Museum

Hailey Johns

The impressive Indus Valley Civilization city of Harappa was first uncovered in 1921, thereby launching excavation in what was once the Indus Valley region. The terracotta bull figurine pictured is one of many of its kind discovered at these sites during the 1980’s. These figurines ranged from depictions of animals, both real and seemingly mythical, to those of the Mother Goddess. Believed to have been produced between 2600 BC and 1900 BC, these figurines are some of the earliest artifacts in modern possession. The figurine displayed was acquired in 1986 at the site of Harappa, in modern day Punjab, Pakistan. It is small in scale, about the size of one’s palm, at 7.50 centimeters tall, 5.80 centimeters wide, and 7.50 centimeters deep. Of all animal figurines discovered, nearly 75% depict cattle, both with and without humps and of slightly different statures. Depicted in this image, we see a bull, without a hump, but with very large, impressive horns.

While the purpose of these figurines is somewhat up for debate, as we do not have any recorded input from the people of the Indus Valley Civilization, scholars largely agree that they were intended either for children to play with or for ritual use. This particular figurine was most likely utilized as a toy. One indicator of this is the bull’s lack of genitalia. This greatly contrasts the animal depictions in Indus Valley seals, in which sexual and reproductive characteristics are almost always clearly displayed. The small size of the figurine also suggests that it may be intended for children. Just as many children today, it is likely that children of the Indus Valley Civilization took a liking to animals. All speculation aside, the many bull figurines uncovered, such as this one, highlight the special relationship between humans and animals across history.

Fragment of a schist panel depicting Vajrapani

About CE 200-300

Pakistan

British Museum

Samuel Rodick

This artwork is a fragment of a larger piece of art depicting Vajrapani, the “holder of the thunderbolt” and one of the Buddha’s top attendants. The art shows the great diversity of northern India at the time, as it uses Greek imagery to depict Buddhist and Hindu gods. Vajrapani is depicted similarly to Herakles with the lion-skin headdress and a thunderbolt that references either Herakles’ club or the thunderbolt of either Zeus or the Indian god Indra. These influences were found due to the influx of Greek people and Greek culture into Northern India due to trade and the conquests of Alexander.

This style of Buddhist art with heavy Greek and Hindu influences originated in the Gandhara region, and thrived during the reign of the Kushans. While the base imagery of Gandhara art remained Indian, contact with and exposure to Roman art led Gandharan Buddhist artists to adopt a number of motifs from Roman and Greek art. Gandharan sculptures were usually made of schist, like this piece, or phyllite and were originally painted and gilded. Time, however, has worn the decoration off of this relief. Often in Gandharan art, the Buddha was depicted with the youthfulness of Apollo and the Buddha and his disciples’ appearances were depicted in an idealized manner.

For many centuries, the northern portion of the subcontinent was home to a number of Greek kingdoms and cities, in the years after the death of Alexander, and these Greek communities imported their religion and culture to the region, such as the city of Taxila in what is now Pakistan. While there had been contact between Greece and India before Alexander’s conquests, it wasn’t until this point that major communities of were established. Alexander and his successors attempted to Hellenize the regions they conquered, and encouraged the spread of Greek culture and people to the eastern colonies. Greek and eastern religions mixed during this period, facilitating the creation of art like this relief which blends Indian and Greek religious motifs and symbols. Trade over the silk road and across the Indian Ocean also linked South Asia with the Mediterranean world, and luxury goods including art was spread. A hybrid Indo-Greek culture flourished in much of what is now Afghanistan and Pakistan, with the creation of the Kingdom of Bactria, and the presence of this kingdom to the Northwest furthered the cultural osmosis between the Greeks and Indians on the Indo-Gangetic Plain. The cultural syncretism in Bactria, according to some historians, has not been matched anywhere else.

Greeks in India did not look back to the west for cultural Hellenism, but to India itself. Many Greeks converted to Hinduism and Buddhism, yet retained a number of their own gods and syncretized their older beliefs with their new faiths. Early on, many Greeks resisted conversion, however, and early Indo-Greeks were at first antagonistic to gods like Krishna, who many of their descendants would worship. This panel depicts a later period, when Greek and Indian faiths acted in concert, and when Greek culture and art had permeated India.

Sources:

Plaque at the Museum

https://www.britannica.com/art/Gandhara-art

https://www.worldhistory.org/article/208/cultural-links-between-india–the-greco-roman-worl/

https://greekreporter.com/2022/08/20/ancient-greek-hinduism-gods/

Standing Figure of The Buddha

200 A.D.

Northern Pakistan

Saanvi Mahadasu

This is a standing figure of the Buddha that is carved in a gray stone, also known as shist. The Buddha is seen wearing a robe, with his hair in a top-knot or ushnisha. The ushnisha is symbolic of the warrior caste that the Buddha was born into, in which they did not cut their hair. His eyes are closed and his facial expression seems peaceful, suggesting that the artist may have carved him in a state of meditation. In addition, it is visible that the figure was originally carved with hands, but they have been lost most likely due to the effects of time and transportation. The part of the right hand that remains looks to hold a mudra, which is a gesture held in the hands and fingers and has various meanings in Buddhism and Hinduism.

The Buddha was born Siddhartha Gautama in modern-day Nepal. He was born into royalty and wealth. Siddhartha was sealed off from the suffering of the outside world, and he never had to experience anything particularly upsetting. However, when he reached adulthood, he learned of aging, sickness, death, and more. He came to the realization that suffering is inevitable. He set off on a path to attain enlightenment and reached it through his own findings and teachings. He taught people about the Four Noble Truths as well as the Eightfold Path to enlightenment. His disciples continued to maintain and develop his teachings. Buddhism spread the most during the Mauryan King, Ashoka’s, rule. Buddhism continues to be widely practiced all over the world.

The style of the figure originates from a tradition in Gandhara, which is part of modern-day Pakistan and Eastern Afghanistan. The style in which Buddha was carved can be traced to Greco-Roman artistic choices. This influence can be seen in the way that the Buddha’s head was carved as well as the folds in the robe. The head is carved similar to how Apollo’s head is traditionally carved, and the folds of the robe resemble a toga. Greek influences can be traced back to when Gandhara was conquered by Alexander the Great in the 4th century B.C.E. His rule likely left an impact on many aspects of culture in Gandhara, including art. The influences of Alexander the Great’s rule as well as that of the Mauryan Empire, Kushan Empire, and Muslim dynasties resulted in Gandhara art being its own genre in Indian art. During the rule of Ashoka, which was in the 3rd century B.C.E, Gandhara had an influx of Buddhist missionaries which led to a plethora of Buddhist art. In the 1st century C.E., the Kushan empire continued to hold a relationship with Rome, resulting in Roman techniques and emblems making appearances in Buddhist art. These influences through trade and continued relationships, as well as various empires, are so riveting because they all came together to create a new culture and form of art.

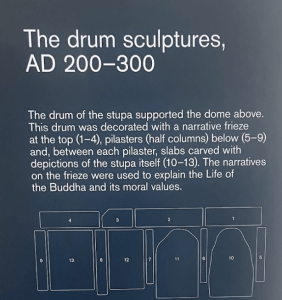

The Drum Sculptures

AD 200-300

Amaravati

British Museum

Isabella Keith

The object is a large limestone slab with intricate carvings and is one part of a stupa drum (#11) that explains the Life of Budha, this one depicting the First Sermon. Originally from Amaravati in northern India, this object was acquired by the British Museum in 1880 and is now shown as a part of the Amaravati marble’s collection. The museum’s acquisition notes state that it was “acquired as the result of the abolition in 1879 of the India Museum (Exhibition Road, London) and the partition of its contents between the British Museum and The South Kensington Museum (Victoria and Albert Museum).” Standing at 150 cm (59 in) tall and 112.5 cm (44.3 in) wide, this was once a part of quite a large stupa dedicated to the Buddha.

While this object is not listed on the British Museums’ own list of contested items, there is debate on where these iconic sculptures belong. These sculptures are known as the “single most important group of Indian sculptures outside the subcontinent” for many reasons. This stupa was once a religious place that was an essential part of many Indians’ Buddhist pilgrimage. Due to its haphazard excavation by the British during their imperial rule, many parts of the stupa have been lost or destroyed, and the majority left are currently located at the British Museum. Being that Buddhism is still a religion practiced today, it is hard to ignore the message sent by Britain withholding these objects that may still hold religious significance to some.

Besides the apparent debate over reparations, these art pieces hold much historical significance and religious information. Put together, the stupa depicts many jatakas, otherwise known as stories of the Buddha’s past lives. This specific piece shows the Wheel of the Law, which symbolizes the previously mentioned First Sermon. A few of the Jatakas and scenes from the Life of the Buddha decorate the rest of the slab in a crowded fashion. This intricate and highly detailed carving shows the importance of these stupas in the earlier day of Buddhism. These stupas were to be packed with as much religious iconography as possible, with little to no space wasted. These carvings continue to be studied today by Buddhist scholars and historians alike trying to understand the history of such a prolific religion.

Links:

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/A_1880-0709-87

https://www.britishmuseum.org/blog/power-patronage-great-shrine-amaravati

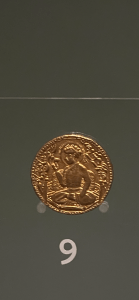

The Kumaragupta coins (no. 3) date back to the 5th century Gupta Empire. Known as the Golden Age, it existed approximately 1,600 years ago. It spanned from North India to most of the subcontinent, leaving a lasting impact on religion, power, and art.

The Gupta kings set many of the enduring forms of Hinduism. By commissioning images of gods, building temples with priests, gifting land to brahmins, and incorporating Hindu teachings in education, the religion played a key unifying role during this time in India’s history. The Guptas were a stable empire with great wealth that recognized the power of art, which explains the success of a government-backed mass religion that’s still practiced today. Additionally, the empire’s opulence, power and artistry were catalysts for commissioning art and architecture that could be understood by anyone in multilingual empires (compared to written works restricted to the educated speakers of one particular language).

Made of solid gold and the size of a penny, these two coins depict Kumaragupta I, who ruled from 414 to 455 AD. One side [on the right] portrays Kumara, the god of war, with a spear and a wartime peacock. He is riding the bird into battle— starkly different from European depictions of the same animal as majestic and calm. This image of Kumara from 1,600 years ago is still recognizable today, present in many shrines. He and his peacock are standing on a plinth, meaning it’s depicting a statue of the god; this is the beginning of temple imagery that still continues into modern times. The other side of the coin, on the left, is King Kumaragupta offering grapes to a sacred peacock. He is adorned with a crown and elaborate jewelry, and the inscription describes him as “deservedly victorious with an abundance of virtues.” This clue points to the fact that Kumaragupta was respected as a leader due to his success. Additionally, these coins communicated that the royal ruler enjoyed the favor of Heaven, therefore asserting his supremacy. The coins are a form of mass communication that were invented around the death of Alexander, proudly utilized by leaders ever since.

The depiction of Kumara on the coins reflects a universal concept shared by nearly all of mankind: the desire for a personal connection with the divine. This inclusivity aspect is key because the message is that everyone, not just the king, could access holiness the same way. This religious dynamic, mediated through statues and images, remains a hallmark of Hinduism to this day. The Gupta period solidified the central role of the Hindu deities and their worship in Indian religious practices.

In short, many aspects of the Gupta Empire under Kumaragupta’s rule are revealed through their currency; the miraculous golden age is depicted by these literal golden coins. The historical narrative of Kumaragupta’s impressive opulence, religious contributions, and strong authority over India is captured by these exquisite objects. They serve as a reminder of a remarkable period that continues to shape India’s cultural landscape.

Image of Tara

800 CE

Sri Lanka

British Museum

Mir Shah

The “Image of Tara,” coined by British archaeologists, is a figurine displayed at the British Museum in London, crafted in the 8th century CE in between the city of Trincomalee and Batticaloa (modern day Sri lanka). Using gilded bronze and gold, the magnificent statue is approximately 4 and a half feet tall in length, or around 143 centimeters, while the width of the statue is 44 centimeters. The statue is representative of the Buddhist Goddess of compassion, and one of the 10 Hindu Mahavidyas, Tara, and was found in Sri Lanka around 1830 by British archaeologists, who later named the work of art. The figurine itself is breathtaking, but even more impressive is the attention to detail; the craftsmanship of fingers, the stomach, breasts, and even the closed eyes, making it a detail oriented work of art. In addition, the materials used in the construction of this piece are still well preserved, including the use of bronze and gold, with minor scratches and limited damage to the figurine itself. The elongated ears of the figurine are similar to Buddhist statues that are common in East Asia. The position of the right hand is in varadamudra, which is the gesture of giving, and the left hand positioned katakahastamudra, which is the art of holding a flower, figuratively. The upper body is completely uncovered and the bottom part of the figurine covered. The Image of Tara is reflective of classical Sri Lankan artwork.

The Image of Tara is important in understanding the presence of Buddhism, particularly Mahayana Buddhism, and Hinduism in Sri Lanka. As Tara is a Buddhist Goddess, the discovery of this statute provides evidence for the widespread practice of Buddhism within the tiny South Asian country. Tara, is the Buddhist Goddess and a Bodhisattva, which is a deified individual that represents nirvana, or enlightenment. The role of Tara, in Buddhism, is to assist individuals in their suffering, offering them compassion and liberation from the evils of the world. Interestingly enough, Tara is also mentioned in the Rig Veda and one of the principle Goddesses (Mahavidyas) in Hinduism, which are all avatars of the mother Goddess, Mahadevi. While Tara was recognized around 1500 BCE, evidence of her worship is found around 500 CE, however, there is speculation that she may have been worshiped in the Indus Valley Civilization, particularly under the Shakti sect of Hinduism, which highlights the female divine. The presence of Tara in Hinduism, is attributed to the story of Shiva and Sati, where after Sati’s self immolation, her body was scattered across the Indian sub-continent, where each site containing a piece of her body (pith in Hindi) led to the establishment of various other Goddesses, with Tara being one of them.

The Image of Tara statue that we see today in the British Museum, was ‘given’ to sir Robert Brownrigg, where it later found itself in the museum. Interestingly enough, the statue was originally seen as too obscene and ideal of exotic fantasies of the East, thus, the statue was taken off display for quite some time. Nonetheless, the figurine is extremely important in understanding the expansive influence of both Hinduism and Mahayana Buddhism in Sri Lanka.

Stone Bracket Figure from a Hoysala Temple

About 1100-1200

Karnataka, India

British Museum

Advika Raj

This sculpture is of a bracket figure, specifically a female dancer, with another female figure shown playing the drum. These figures are made of stone and delicately carved to detail their jewelry and costumes. They are adorned with headpieces, necklaces, bracelets, and anklets. The leading dancer is positioned with crossed feet and a mirror in her left hand. Additionally, these pieces are from the Hoysala era from around 1100 to 1200. In general, these figures were situated at an angle between the wall and the roof of the temple. Even though this particular piece was unsigned, Hoysala sculptures typically included the artist. These signed engravings showcased the sculptors and their work in various temples. Sculptures with signatures seem to be more prevalent in Hoysala pieces of art than in those from other Indian works.

As a recurring theme in the architecture, dance was a large part of the culture and of Hindu rituals, which was illustrated in temple dances. As a traditional dance style, Bharatnatyam grew throughout the Hoysala dynasty. Similar to the figure, sculptures and brackets on the outside of temples exhibited numerous female dancers.

The Hoysala era was centered in Karnataka, India, and also included parts of present day Tamil Nadu and Telangana. This was a time of notable art, architecture, and cultural accomplishments. The previous dynasties, Western Ganga and Nolamaba, were influenced by Tamil culture and built Hindu and Jain temples. On the other hand, Western Chalukyan architecture was the source of inspiration for the Hoysala empire. Further, they desired to exceed the Western Chalukyan Empire in architecture and created more figure sculptures. Soapstone was used because it provided better clarity, which allowed for depictions of scenes from epics.

About 100 of the nearly 1500 temples built during the Hoysala dynasty still remain. These temples display a fusion of Indian architectural traditions. Moreover, the temples were typically star-shaped, embellished with stone carvings that represented religious and cultural practices. The majority of these temples were dedicated to Hindu gods, including Shiva and Vishnu. Some of the prominent temples are the Hoysaleshvara Temple and the Chennakeshava Temple. The Chennakeshava Temple is in Belur and honors Vishnu. It is known for its iconography, sculptures, and friezes, which display the culture, including dance and music. These details are engraved throughout the exterior of the structure.

The Hoysaleshvara temple is located in the Halebidu village, Karnataka, India. It is known to be one of South Asia’s most detailed architectural structures. The temple, built with schist rocks, is covered with sculptures of gods, goddesses, and divine beings. Elephants, horses, and other sculptures detail the outside walls in a zigzag pattern. The Hoysaleshvara temple, constructed around 1120 CE, honors the Hindu god Shiva. It was one of the first temples built at Halebidu, which served as the Hoysala dynasty’s capital from around 1000 until 1346. It is the largest Hoysala temple that remains, and its design exemplifies the Hoysala style.

The Divine Couple Shiva and Parvati

1200s

Orissa, India

British Museum

Kaylie Nguyen

This beautifully carved stone sculpture displays Shiva, one of the most worshipped gods of Hinduism, and his consort Parvati. Shiva is recognized as the Destroyer whereas Parvati is known as the Goddess of Love, Devotion, and Fertility. When paired together, Parvati offers the perfect balance to Shiva’s untamed passion. The union of the couple in the above sculpture represents the idea that the universe is founded upon both male and female principles. Also depicted is the sage Bhringi, who was a loyal devotee of Shiva. Bhringi adamantly refused to honor Parvati until eventually, she sat on Shiva’s lap and Bhringi finally conceded. Thus, the couple are often portrayed together in order to show their partnership. The sculpture shows both the gods’ respective animals below their feet, namely Shiva’s bull Nandi and Parvati’s lion Dawon.

An important characteristic to note is Shiva’s third eye, which symbolizes his wisdom and knowledge. It is said that Shiva burned the god Kama in anger with his third eye, hence why he is called the Destroyer. The trident above the gods’ heads has three prongs to represent how Shiva is part of the trinity of Hindu gods (called the Trimurti), which includes Brahma the Creator and Vishnu the Preserver. Another important symbol is Shiva’s cobra necklace, which illustrates Shiva conquering and dominating the world’s most dangerous creature.

Puja, also known as worship in Hindu culture, can be performed at home or in a temple. People make offerings in the form of fruit or flowers to show their reverence to a deity. The gods give their blessings to their followers in return through prashad. Prayers are chanted and songs are sung. For Lord Shiva specifically, Monday is his special day of worship. People fast for Somvar Vrat in order to receive Shiva’s blessings.

The sculpture was found in Orissa, which is modern-day Odisha; this state in eastern India is well-known for its majority Hindu population and its multiple Hindu temples. One of the most notable is the Lingaraja Temple, located in the capital of Orissa and honoring Shiva as its main deity. The sculpture was approximately made in the 13th century CE, which coincides with the time in which the Delhi Sultanate began to invade northern India. Led by Muhammad of Ghor, the intrusion began the diffusion of Islam, driving Hinduism further south into the subcontinent. The Delhi Sultanate repressed Hinduism by raiding or destroying Hindu temples and taking Hindus as slaves. They also smashed religious sculptures and art, but despite this, Hindus still continued to practice their faith, as seen by this surviving sculpture. The display would likely be exhibited above a temple door or within the temple itself. Typical sculptures during this time were made of stone, bronze, or terracotta and not made of materials such as clay because India’s warm climate inhibits the permanent survival of sculptures made out of organic materials.

Piggy Bank

15th Century

Majapahit Kingdom, eastern Java

Ashmolean Museum

Sam Rodick

This piggy bank is made of terracotta, and originated in the Majapahit Kingdom of eastern Java in the 15th Century. The world’s first piggy banks originated in Java and are remarkably similar to the ones used today. One major difference, as seen in this one, is the lack of a hole at the bottom or other means of releasing the coins. Instead, one would have to destroy the piggy bank to retrieve their money. Due to this, very few Javanese piggy banks survive unbroken like this one. The fact that one had to destroy their piggy banks, especially ones as intricately carved as this one, in order to retrieve their money made the decision more difficult and encouraged fiscal responsibility and savings.

The oldest extant piggy bank comes from Java and was made in the 12 Century CE in the lands of the Majapahit Empire. This empire is said to have controlled parts of what is now Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia, Thailand, Brunei, and Singapore for over two hundred years between 1293 and 1527, although the exact size of the empire is contested. They were esteemed for their terracotta art and were “the last Indianized kingdom in Indonesia”. They were founded by Vijaya, a prince who took control over the island of Java first with the help of the Mongols, before turning against them and pushing their forces off of the island. They rose to be stronger under his rule, and the empire reached its height under King Hayam Wuruk. They maintained diplomatic relations with major powers of East and Southeast Asia, yet eventually fell due to rivalry with Islamic states in northern Java.

The rule of Hayam Wuruk is remembered as a golden age of Javanese history. Shaivite Hinduism and Mahayana Buddhism were widely practiced in the empire, however poems do also venerate the king and suggest that he wished to be viewed as a messenger for or representation of a god. Many scholars from India traveled to Java and a Javanese poet asserted that Java and India were prestigious due to their high numbers of religious experts. The Majapahit served as a nexus for trade and there was considerable contact between them and India as well as China. There was also significant religious conflict between Hindus and Muslims in Indonesia and after the fall of the Majapahit there was conflict between Islamic and Hindu statelets to fill the power vacuum.

https://www.ashmolean.org/professor-colin-mayer-piggy-bank

https://generalist.academy/2022/01/19/first-piggy-bank/

https://www.britannica.com/place/Majapahit-empire

https://www.britannica.com/place/Indonesia/The-Majapahit-era

Brass ewer

1500-1550

Lahore or the Deccan

Ashmolean Museum

Ella Grace Collard

This brass ewer dates back to 1500-1550. Sometimes referred to as the Butler ewer, it was previously in the collection of Dr. A.J. Butler, Bursar of Brasenose College, before being given to the Museum by his daughter. The beautiful object represents a history of cultural fusion through art in India during the Mughal empire. Indo-Islamic metalworking of this time conveyed the lavish lifestyle of the nobility as well as the fast-paced economic development facilitated by trade. The Mughals were one of the wealthiest nations in Indian history and it is through ancient objects that we can peer into this historical era.

As for the ewer’s physical characteristics, it has a tall, tapering neck and spiral-fluted body. This style of art is unique to an Indo-Islamic metalworking that emerged from India as well as foreign influences brought in by Islamic conquerors. The detailed designs show the cultural overlap of these two civilizations during the Mughal period. The skinny neck and spiral fluting of the ewer can be attributed to Islamic influence, while the more organic shapes and decorative schemes are Indian artistry. This fusion of styles was no accident; it was part of broader cultural exchanges facilitated by trade. Other metal goods as well as textiles, food, accessories and more were also bought and sold by intermingling people during this time. The growth of Mughal India’s prosperity was closely tied to its extensive trade networks. The Deccan region was known as an exporter of gemstones and gained immense popularity due to increased foreign demand. This popularity only increased the region’s wealth as tourism resulted from its success. It attracted diverse visitors, turning Deccan into a vibrant cosmopolitan center. This led to further cultural diffusion, greatly impacting the aesthetics and craftsmanship of the time. Perhaps this ewer belonged to a wealthy tourist, or a rich local businessman.

The ewer, therefore, offers more than just an insight into the elite’s lifestyle during this period; it also indicates the wealth divide in the society. The impressive craftsmanship, rare materials, and detailed design underline the disparities between the affluent minority and the peasant majority. In a way, the ewer’s presence in the museum serves as a physical reminder of the social and economic conditions of the time that have not been resolved since, such as the wealth gap in South Asia.

Finally, besides the cultural and social significance, one should consider the functional aspect of the Butler ewer. On a day-to-day basis, the object was mainly used for handwashing. But occasionally, it was used to welcome visitors by pouring scented water over their hands and feet, an act of hospitality and politeness towards guests. Thus, this brass ewer not only symbolizes India’s complex culture and economy but also provides insight into the traditional customs of hospitality in the region.

Overall, this seemingly simple brass ewer reveals the Indo-Islamic cultural fusion that marked the Mughal period. Being both a work of art and a functional object of the home, ewers, along with other important metalworks, served as key objects in historical Mughal India. This piece speaks to the enduring traditions and customs of the region, providing us with a tangible link to the past.

The Battle of Patan

1590-1595

Mughal Empire

Victoria and Albert Museum

Kaylie Nguyen

The beautiful miniature paintings above illustrate the Battle of Patan, which resulted in a Mughal victory over Gujarat in 1572. Through the paintings, one can see the use of elephant warfare, which was common at the time, and the city in the upper corners. The clash of the armies is illustrated by the difference in dark and light coloring of the armor. The Mughal force was led by Qutb ad-Din Khan and Azim Khan while the enemy force was led by Muhammad Husain Mirza and Sher Khan Fuladi. This victory expanded the borders of the Mughal Empire while giving them access to more resources. Furthermore, Gujarat’s proximity to the sea fostered maritime trade through the Arabian Sea and Indian Ocean, which connected them to other major powers of the world such as the Portuguese. In terms of expanding the territory of his empire, this battle is a significant example of Akbar’s strength and multitude of accomplishments. Akbar, often referred to as the greatest Mughal ruler, conquered and consolidated much of the land in northwest India. By the end of his rule, his empire would extend from Kandahar in the northwest to Kashmir in the north to Bengal in the east. In addition to his military domination, Akbar developed political alliances by taking Rajput wives. The inclusion of these Hindu Rajputs into the empire earned him their respect and emphasized Akbar’s religious tolerance. He also abolished the taxation on non-Muslims, called the jizya, and permitted Hindus to serve in top government positions. Akbar established a new religion named the Divine Faith, or Din-I-Ilahi, by combining elements from existing religions. He reorganized his army into the mansabdari system and emphasized the value of merit on gaining mansabdar status. Among his many achievements, Akbar built the city of Fatehpur Sikri with its beautiful Jami Masjid mosque.

The miniature paintings originate from the Akbarnama, which is a chronicle of Akbar’s life. Written in Persian, Akbar commissioned a court historian named Abu’l Fazl to assemble this manuscript between 1590 and 1596. Its incredible detail and vivid colors reveals the intricacy of these one hundred and sixteen illustrated folios. The pages consist of three sheets of paper painted in opaque watercolor and bordered by a thin strip of gold. Some of the most reputable artists that contributed to the Akbarnama were Farrukh Beg, Basawan, and Lal. For these particular miniatures, they were put together by Lal, but the left painting was done by Manu and the right painting was done by Dhanun. After Akbar’s death, the manuscript was stored in the library of his son, Jahangir. The Akbarnama currently displayed in the Victoria and Albert Museum was bought from Frances Clarke in 1896. It had been in the possession of her husband John Clarke, who purchased it when he was the Commissioner of Oudh (located in northeast India) from 1858 to 1862. Despite the numerous hands that it has passed through and the belief that this is the earliest illustrated copy, the Akbarnama and its miniature paintings still retain their brilliant colors in order to clearly depict the life of Akbar the Great.

Pendant

About 1610-1620

Mughal Empire

Victoria and Albert Museum

Sam Rodick

This pendant was crafted in the 17th century in the Mughal Empire. It is made of white nephrite jade but is ornamented with rubies and emeralds and mounted in enameled gold. The rubies are set using a technique called Kundan, which is similar to cloisonné. Cloisonné is an enameling technique where metal strips, in this case made of gold, are attached to a surface, leaving cavities that are then filled with enamel paste. The technique was invented in the eastern Mediterranean region in antiquity, and practiced by the Egyptians and Mycenaeans. The Byzantines would later take a strong liking to the practice and it would spread eastward from there, becoming very popular in China and Japan. In Kundan, an antimony paste is used, and then gemstones are placed on top of and into the cavities, setting them in the paste. Gold foil, also known as Kundan, is then forced into the edges, and is shaped by them to separate the gems.

The main body of the pendant is shaped similarly to a vase or arrowhead, with a large ruby in a floral motif in the center. Peppered throughout are depictions of flowers, plants, and birds. Gardens were important to the Mughals, and flowers are incredibly common in Mughal art, both secular and religious, often decorating the borders of paintings either by themselves or when paired with calligraphy. A number of Mughal rulers, such as Jahangir (under whose reign this pendant was likely created), were very interested in the natural world and collected rare and exotic flowers, birds, and animals. The popularity of flowers in Mughal art increased as contact with the Europeans did, and Mughal artists took inspiration from Dutch prints and engravings. Birds were often found in Indian art before the Mughals, but Jahangir took a special interest in commissioning art including and focusing on them and on other animals.

Nephrite jade was a very rare commodity in India when this pendant was made, and was difficult to fashion, as it cannot be carved and so has to be abraded or incised with diamond drills. The jade was imported from Khotan, a central Asian kingdom that was difficult to reach, and was used by master craftsmen and lapidaries in a variety of innovative fashions. Most work with Nephrite jade, likely including this pendant, were made in the imperial workshops.

Functionally, this pendant would have served as the central piece of a necklace, with a hole along the top edge for a thread or chain. The form, similar to an arrowhead, likely derives from arrowhead-shaped pendants that were once popular and believed to provide protection to their wearers. The eyes of the birds are made of emeralds and the back of the pendant has a verse from the Koran, giving it religious significance. It was likely made for Emperor Jahangir, as the birds depicted, hoopoes, were associated with Solomon, a figure who Mughal emperors were often compared to.

Museum Plaque

https://www.britannica.com/art/cloisonne

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S_HluttcJcw

https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/the-arts-of-the-mughal-empire

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O96353/pendant-unknown/pendant/

Mughal Coin from Jahangir’s Era

1618-1625 CE

Ashmolean Museum

Mir Shah

Description

The coin displayed above is currency dating from the Mughal Era, particularly under Emperor Jahangir. The coin is made of gold, however, Jahangir issues multiple variations of this coin, and others that include astrological signs, in metals such as silver. There are 13 total styles of coinage that Jahangir issues, one which is a bust of the emperor himself, and the other 12 which represent each of the months, and their respective astrological signs. On the back of this coin, and the other 12 coins minted during the era of Jahangir, there are various verses of Persian poetry, some of which discuss the power and might of the Mughal emperor, and the empire itself. One notable instance of poetry is a couplet, in which the beauty of Jahangir’s wife, Empress NurJahan, is mentioned in detail. On the back of some of the coins, there are verses in the Persian (Farsi) script paying tribute to Jahangir, including:

یافت در اگره روی زر زیور از جهانگیر شاه، شاه اکبر”

The line above translates to “the face of gold was decorated in Agra by Jahangir Shah, son of Akbar.” When analyzing the coin, one is struck by the beauty and intricate detail of the coin, alongside the emphasis on Persian and Indian elements. In the coin above, Jahangir is shown to be sitting with his legs crossed, holding a glass or goblet in his hand, with Persian calligraphy above his head paying tribute to his reign.

History

Under Mughal Emperor Jahangir, Mughal coinage shifted from traditional coinage, which was mostly Islamic calligraphy, to encompass astrological signs and humans. While the Islamic calligraphy used by previous administrations was unique and beautiful in its own way, the shift to this new coinage led to elaborate designs. Jahangir, was quite obsessed with coinage, and a patron of creating coins in an effort to show his grandeur. The coins that included Jahangir’s self portrait, were given, oftentimes, as a gift to followers or members of the court for their turbans, which was shown to bestow his imperial favor upon them. Unfortunately, there are not many of these coins left, particularly the gold ones, which is why the value of the Mughal coins from Jahangir’s era, are extremely high, nearing approximately half a million USD for a single coin. The reason being is that Jahangir was one of the earlier Mughal emperors, known for their relative tolerance and distance from strict adherence to religious practices. For instance, Jahangir was also open to drinking wine, showing his lack of devotion to strict Islamic principles. Ultimately, the coins became rare since Jahangir’s successors, such as Shahjahan, believed that the coins were quite blasphemous, thus, they were pushed out of circulation in the economy, and molten into gold. Therefore, very few of these coins remain to this day, in few personal collections and museums across the globe.

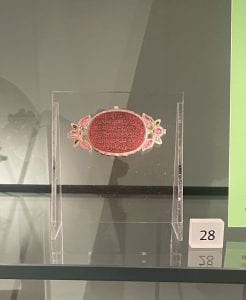

Carnelian Amulet with the Throne Verse

1650 – 1750

The Mughal Empire – North India

The Ashmolean Museum

Hailey Johns

This oval bezel amulet serves as a prime example of the beautiful and intricate craftmanship of the Mughal empire. Once a part of a bracelet, this amulet was the center stone of the piece. It is made of a carefully cut and incised cornelian of an impressive size and quality. Beyond the cornelian itself, the amulet includes a jade setting and gold detailing inlaid with precious stones including rubies and emeralds. Surrounding the amulet and creating a halo along the border are more of these precious stones in leaf-like settings, tying in an added element of nature. The combination of these elements makes for an impressive display of wealth, indicating that this amulet almost certainly adorned the wrist of a royal or noble woman.

The inscription on the cornelian is Ayat Al-Kursi, more commonly known as the Throne Verse. It is the 225th verse of the second chapter of the Qur’an, Al-Baqara. This is denotated as Q2:225. It serves as one of the Qur’an’s most famous verses, hence its placement on the amulet. Incised with Arabic text, the translation reads, “God there is no god but He, the Living, the Everlasting. Slumber seizes Him not, neither sleep; to Him belongs all that is in the heavens and the earth. Who is there that shall intercede with Him save by His leave? He knows what lies before them and what is after them, and they comprehend not anything of His knowledge save such as He wills. His Throne comprises the heavens and earth; the preserving of them oppresses Him not; He is the All-high, the All-glorious.”

The significance of the Throne Verse is great, as it is seen to confirm the greatness of God when it is read or recited. It was thoughtfully chosen as the inscription for this amulet. It describes how no man or thing is comparable to God, holding God in the highest esteem. Given this meaning and the likely owner of the amulet, it can be understood to establish that the royalty and nobility are humble in the face of God and know their place below him.

In addition, amulets were thought to be enriched with protective powers, particularly those with Qur’anic inscriptions. In Muslim culture, it is believed that anyone who touches, reads, wears, or sees such an amulet has the protection of God and the power to ward off evil. These amulets were often made of cornelian, as it is easy to engrave and often associated with health, luck, and royalty. The Mughals were known to be quite superstitious, giving further context to amulets such as this and their supposed protective powers.

Aged Aurangzeb reading the Qur’an

1690-1700

Gujarat or North Deccan

Ashmolean Museum

Kaylie Nguyen

This painting, made at the end of the 17th century, depicts Aurangzeb intensely reading the Qur’an in front of an attendant or courtier. The Qur’an reveals his strong Muslim beliefs that would later impact his policies as a ruler. He is shown in his later stages of life, and his seated position expresses his superiority and dominance over the other figure in the painting.

Aurangzeb’s rise to power was rooted in bloodshed, jealousy, and betrayal. Shah Jahan, the fifth emperor of the Mughal Empire, had four sons; the main conflict was between Dara Shikoh and Aurangzeb. Dara was Shah Jahan’s favored heir and was beloved by the people. He was a scholar, philosopher, and writer amongst other labels. Gentle and compassionate, he differed greatly from Aurangzeb, who was militarily inclined and power hungry. Whereas Dara practiced religious tolerance like his great grandfather Akbar and translated Vedic Sanskrit texts into Persian, Aurangzeb was an orthodox Sunni Muslim. In part, the war between the brothers was religious and it hinted at the long-standing tension between Hindus and Muslims; Dara was supported by the Hindus and Aurangzeb was backed by the Muslims. Furthermore, Aurangzeb resented his father’s preference and this jealousy fueled his antagonism. After Shah Jahan fell ill, the war for the throne began. The battle of Samugarh in 1658 was a critical victory for Aurangzeb and it forced his brother to retreat. Although Dara had the larger army, Aurangzeb’s militia had more experience and Aurangzeb himself was a skilled tactical leader and strategist. Dara was later betrayed by one of his commanders, and he was captured and brought to Delhi. He was paraded through the streets on an elephant as a form of public humiliation. Because Dara was loved by the people and therefore still posed a threat if kept alive, Aurangzeb plotted the assassination of his brother and sent Dara’s head to an imprisoned Shah Jahan. Aurangzeb would rule Mughal India for the next 49 years.

During his reign, Aurangzeb’s severe Islamic beliefs, as evidenced by his reading of the Qur’an in the painting, led to the alienation of Hindus. He reinstated the jizya tax on non-Muslims and destroyed Hindu shrines and temples. In a reversal of Akbar’s policies, Aurangzeb forbid Hindus from gaining government positions and restricted their customs and traditions. The combination of these anti-Hindu practices reduced support from the Rajputs. Aurangzeb did positively contribute to the Mughal Empire by conquering several Deccan kingdoms, such as Bijapur and Golconda. This military expansion coincided with the rise of the Marathas, a warrior group in western India. Shivaji was a prominent Maratha chief who was invited to the Mughal Court by Aurangzeb in 1666 for reconciliation. However, he was disrespected at the court and placed under house arrest, while Aurangzeb decided his fate. Shivaji and his son escaped in a large basket, but his experience would contribute to his discontent and motivate his campaign against the Mughals. Battered from the inside by Hindu resentment and from the outside by the Marathas, the end of Aurangzeb’s reign would mark the decline of Mughal power.

Dagger and Scabbard

Roughly 1700

The Mughal Empire – Indian Subcontinent

The Victoria and Albert Museum

Hailey Johns

This dagger and scabbard, also referred to as the sheath, are thought to date back to the reign of the Mughal emperor Alamgir. Alamgir ruled from 1658 to 1707, with the Mughal empire stretching across much of the Indian Subcontinent at the time. The Mughal empire was known for its fine craftsmanship and high valuation of artistic pursuits, with this piece serving as an excellent example. The hilt, commonly known as the handle, of this dagger depicts a horse’s head. Carved of green nephrite jade and set with ruby and gold detailing, as seen in the eyes and bridle detailing, this dagger is incredibly intricate with no expense spared. The blade is made of carefully cut and sharply angled steel. Finally, the wooden scabbard is covered in a layer of supple velvet, with enameled and bejeweled silver mounts at either end. At 42 centimeters in length, this is an impressive piece to say the least.

That being said, this type of fine workmanship was characteristic of the Mughal empire and served as the rule, not the exception to it. There are many of these beautifully adorned daggers from the time in museum collections today. They were likely utilized not in a practical sense, but in a symbolic one. Daggers, sabers, and swords such as this one were symbols of wealth and power. In Islamic kingdoms such as the Mughal empire, royalty was often presented with one of these objects instead of a crown when it came time for them to take power.

Daggers of the late Mughal period such as this are believed to have been crafted in karkhanas. Karkhanas were centers of manufacturing and craftsmanship under state command during the Sultanate and Mughal periods. Within each karkhana, one could find both apprentices in training and Ustads, or master craftsmen. This type of dagger was likely studied by apprentices but largely produced by an Ustad. The level of production that goes into these types of pieces once again reiterates the idea that this dagger and those like it were almost certainly owned by royalty or nobility.

The contrast between the beauty of the dagger and its intended function serves as a metaphor about the Mughal empire at large. While these daggers were not designed for use in combat settings, they were still finely crafted weapons. The blades of these daggers were extremely sharp and constructed of the highest quality metal by professional bladesmiths. This was intended to reflect the power and status of those who wielded them, while also staying true to the refined aesthetic senses of the Mughal empire. This balance between fierce power and timeless beauty captures the spirit of the Mughals.

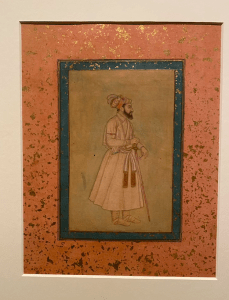

Shah Jahan holding a sword and a rose

1701-1800

India

Ashmolean Museum

Advika Raj

This is a gouache painting, which is a form of opaque watercolor, from the 18th century, with gold on the piece and a gold-flecked border. The first, thinner frame is blue, and the larger border around that is a shade of pink, with both having gold flecks sprinkled throughout. Centered in the painting is a portrait of the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan, who ruled for about 30 years. In his picture, his profile is shown along with him holding two objects. In one hand, he has a long sword on which he is leaning, while the other hand has a rose between his fingers. In several Mughal paintings, these objects reappear as the meaning behind them provides great symbolism. The sword and the rose depict figures of power and authority in dynasties. Many of Jahan’s other portraits have a similar layout, with his body positioned in a way that only shows one side while he grips items. Most pieces have him holding a sword, while the other object is not always the same. In a painting of him made from 1628 to 1629, he is wearing an outfit covered in grand accessories from bracelets and necklaces to armlets and turban jewels. In this, he has a sword while the other grasps an emerald.

He experienced several rebellions during his time in power. A couple, in particular, were against the governor of Deccan, Khan Jahan Lodi, and a Hindu chief from Orchha, Jujhar Singh. Shah Jahan was responsible for defeating and killing both of the opposition. However, this further impacted problems he was facing in the Deccan region, as attitudes towards each other continued to change.

Moreover, architectural creations and accomplishments experienced one of their highest points during the reign of Shah Jahan. He ruled from 1628 to 1658, and the architectural peak was experienced from 1592 through 1666. Shah Jahan built the Taj Mahal. There is a lot of symbolism and meaning associated with this site. The Taj Mahal, which represents stability, power, and confidence, depicts the peak of the Mughal Empire. The structure is a mausoleum constructed by Jahan for his wife Mumtaz to express their love. Its entire idea and style and Jahan’s use of white marble give it enormous force and majesty.

The Taj Mahal was built by Jahan using new ideas. The empire brought about many of the experienced craftsmen needed for the project. Caligraphers, finial makers, and stone and flower cutters all came to work on this immense undertaking from Shiraz, Samarkand, and Bukhara, respectively. While others also arrived from different parts of the Islamic regions. However, the money he had spent during this time on the buildings and military expenses left the treasury without much, resulting in Jahan having to raise taxes. This act was not received well by the people. In addition, under Jahan’s power, the capital was relocated to the Red Fort in Delhi, bringing the fort to the center of Mughal dominance.

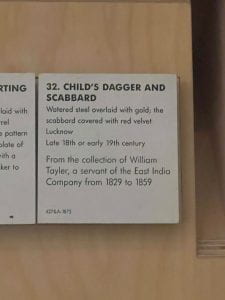

Children’s Dagger and Scabbard

Late 18th or Early 19th Century

Lucknow

Museum – Victoria and Albert Museum

Isabella Keith

Made out of watered steel overlaid with gold this dagger was made in the late 18th to early 19th century for a child and came with a scabbard, or sheath, to hold it covered with red velvet. The museum traces the set of objects to the personal collection of a servant for the British East India Company named William Taylor. Before that, its origins most likely lie in the region of Lucknow, but that has not been confirmed. What the V&A Museum can confirm, however, is that the dagger is indeed Mughal in origin.

This dagger is a very small punch dagger measuring 15 cm in length and has a triangular blade. The handle of the dagger is a transverse handle, which is what makes it a punch dagger, and has straight guards on each side. This design of a grip perpendicular to the blade is also known as a katar dagger. The side guards, or flanges, are often ornamental and decorative while also protecting the holder’s hand and wrist.

The katar blade is a type of push dagger that originated in South India and is unique to the Indian subcontinent. It is also the most famous type of Indian blade. While the katar is a very practical weapon, its uses were not just in being a weapon. The katar has often been used as a status symbol, with Kings and other influential figures often pictured wearing them to signal their wealth and their position. Some upper-class Rajputs would hunt tigers using katar blades, as killing a tiger with this weapon at short range signaled their skill and bravery. Another use for the katar was ceremonial, and some katars were made specifically to be used for worship and ceremonies.

This katar was made small in order to be proportional for a child. The child in question was almost certainly either a young royal, such as a prince, or an aristocrat of similar standing due to the use of gold in the handle. This was most likely made to be used as a part of some sort of ceremony or to be worn as a part of ceremonial dress, as small children often were not the ones fighting in battles. However, the dagger could also have been made to give a young wealthy child a means of self-defense, as the katar was designed to be more easily able to pierce chain mail armor than other daggers. Many katars had thickened tips in order to make the blade stronger and less likely to bend or break. Also, many sheathes for katar daggers had to be covered in fabrics such as silk or velvet due to India’s humid climate, which is most likely why this child’s scabbard is covered in red velvet.

Rama

1800 (circa)

South India

British Museum

Saanvi Mahadasu

This picture is a wooden sculpture of Rama as the King of Ayodhya. He is holding a bow and arrow, which was his weaponry of choice. Rama is a part of the epic, Ramayana, in which he rescues his wife Sita from Ravana. After Rama married Sita, he was exiled from the Kingdom of Ayodhya for 14 years. His brother, Lakshmana, joined Rama and Sita during their exile. Sita was abducted by Ravana and Rama assembles an army of monkeys to save her. This includes Hanuman, worshipped as the monkey god that led the mission to save Sita. After Sita is rescued, they return to Ayodhya and Rama takes over the throne. However, the people of Ayodhya had doubts about whether Sita had remained loyal to Rama during the time that she was in Ravana’s house. When Sita is told of this, she exclaims that she was loyal to Rama and forces Laskhmana to set a fire to prove her loyalty. Sita then walks through the fire and walks out without any injury. After seeing that Sita was in fact loyal, Rama begs for her forgiveness.

Rama’s journey to the throne is not a traditional one. Rama was the rightful descendant to the throne after his father, Dasaratha, as he was his oldest son. Rama was the son of Kausalya, the chef wife of Dasaratha. Kaikeyi, another wife of Dasaratha, convinced him to exile Rama from the kingdom so that her son, Bharata, could be the king. Dasaratha ends up passing away from a broken heart, caused by Rama’s exile. When Bharata learns about his mother’s plot, he goes to find Rama and invite him back to the throne. However, Rama refuses to return from his exile until it is over. To symbolize the rightful heir to the throne, Bharata places Rama’s sandals at the foot of the throne. When Rama returns to Ayodhya with Sita, he returns because his promise to his dad, that he would be exiled for 14 years, is completed. The sculpture depicts him as the King after this journey, we see this through the throne that he is sitting on and the way he is decorated with jewelry.

Rama is told to have followed the principle of Dharma throughout his life. Dharma holds many virtues, but mainly involves being honest and morally correct in one’s decisions. For example, if a king or leader were to follow Dharma, they would have to take the best decisions for their people. This principle brings up a discussion about righteousness in the chastity test given to Sita. As a king, Rama might have been motivated to do right by his people. However, as a husband, this was not the morally right decision to make. Through looking at this epic in different roles, we can see the nuance that Dharma brings to Rama. Rama was not individually worshipped until the 14th or 15th centuries, and he was worshipped before then as an incarnation of Vishnu. Now, there are temples dedicated to Rama, accompanied by Sita, Laskhmana, and Hanuman.

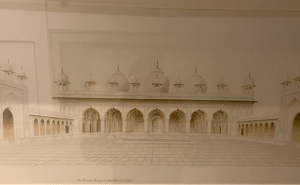

The Moti Masjid, Agra

1816-22

Victoria and Albert Museum

Advika Raj

This watercolor piece is of the Moti Masjid in Agra, painted by a Delhi artist. The architecture of the building is detailed by the domes and curved arches, providing dimension to the landscape. The colors are light and minimalistic, with neutral looks that draw the viewer to the minute details. It is known as the Pearl Mosque due to its white marble that creates an iridescent appearance.

The Moti Masjid or the Pearl Mosque, was built by Shah Jahan. The Mughal Emperor, Shah Jahan, ruled from 1628 to 1658. During Shah Jahan’s reign, there was also significant literary production, calligraphy, and painting. His court also had a large collection of jewels. Furthermore, Shah Jahan had a passion for building. In terms of architecture during his reign, the most prominent construction was the Taj Mahal. In addition to undertaking the Taj Mahal, he also managed the construction of two huge mosques in Agra, his initial capital: the Moti Masjid and the Jami Masjid or Great Mosque.

The Moti Masjid was completed between 1648 and 1655. The arrangement of arches along the prayer hall’s eastern elevation was unique for a mosque, which typically had a more pronounced central entrance to emphasize the axis moving to the mihrab. The mosque is oriented east to west, along the hill, and overlooks the Yamuna River. It was constructed on a high foundation on a terrain that slopes towards the east. On top of the prayer hall are three spherical domes covered in white marble. The central dome is bigger than the other two, and there are two of them. The domes are rounded and have lotus finials on top. The four corners of the prayer hall are defined by octagonal pavilions supported by thin columns and covered with domed roofs. An inscription in Persian, written in black marble, appears above the arches. This writing praises Shah Jahan and the mosque.

This Mosque is found in the Agra Fort. Akbar constructed the Agra Fort in the 16th century as a military base and as a residence. It was said to have taken eight years to build. The fort’s walls are about 70 feet high and surrounded by a moat. The walls have two entrances: the old Delhi Gate, which is covered with exquisite marble inlays, and the Amar Singh Gate, which faces south and is currently the only access point into or out of the fort. Subsequent Mughal kings, particularly Shah Jahn and Jahangir, constructed several structures inside the walls. In addition to the Pearl Mosque, inside the Agra Fort also lies the Jahangiri Mahal, also known as Jahangir’s Palace, which Akbar built for his son Jahangir. It is the most considerable portion of the structures. Additionally, Aurangzeb imprisoned Shah Jahan in the Agra Fort after he took power.

Golden Throne of Maharaja Ranjit Singh

1818

Victoria & Albert Museum

Mir Shah

Description

The Golden Throne of Ranjit Singh is one of many objects highlighting Indian culture at the V&A museum. The throne is average sized, not excessively large, however, it is made entirely of gold. The throne is meant to display the greatness of the maharaja, and is heavily ornamented with various pillows and cushions, which provide support and a sense of elegance to the throne, alongside strings and ropes meant to give it a finished look. The designs surrounding the throne are distinctive and depict various images of the lotus, which is scattered throughout the exterior of the throne. In traditional Sikhism, The lotus is representative of purity. The throne is held up by 8 legs, and the back of the throne is upright, in an attempt to provide back support to the occupant.

Historical Context

The throne was designed and created by Hafiz Muhammad, in modern day Lahore, Pakistan. While scholars disagree on the exact date the throne was constructed, it was likely constructed after the fall of Multan to the Sikh army, after the defeat of the Afghans around 1818. The throne is believed to have been constructed by Maharaja Ranjit Singh of the first Sikh Empire as symbolic of his victory over the Afghans. Ranjit Singh was quite significant in Indian history, and world history, as a whole, as he was the founder of the first Sikh Empire, and was one of the very few of India’s rulers to push back against India’s traditional invaders: the Pashtuns from Afghanistan. Ranjit Singh was uneducated, however, he was extremely progressive in his treatment of ethnic and religious minorities, allowing even a large number of Hindus and Muslims to be a part of his military apparatus. His empire stretched throughout the entirety of Punjab, all the way to the Khyber pass, near the Pashtun homelands. Using European styles of warfare and technology, Singh was able to combat his more powerful rivals in the region effectively. Singh even hired European officers, many of whom served under Napoleon, to fight head to head against the Afghans. In his personal life, Singh was known to enjoy the luxuries presented to him, but also was quite humble at times. In addition, Singh was known to be blind in one eye. Ultimately, after one of his last victories, in which he aided the British, Singh became ill, and died in the city of Lahore. Singh’s assistance to the British was initially successful, however, ultimately, the British failed to install their own government in Afghanistan. After Singh’s death, his empire began to crumble, with Punjab eventually subdued by the British and annexed into the British Raj. In 1849, the British East India Company (BEIC) seized the throne of the former Maharaja, initially storing it in Calcutta, and later taking it to the Indian museum in London. Ultimately, in 1879, the throne was taken to the V&A museum and has since remained.

Kali

1865

Kolkata, India

Victoria and Albert Museum

Saanvi Mahadasu

This is a watercolor painting of the Hindu goddess Kali with lithographed outlines. She is painted with dark skin and four arms. Her tongue is sticking out, with blood dripping from her mouth. Her third eye is painted on her forehead, corresponding to her marriage with Lord Shiva. When taking a closer look, one can see that she is wearing a garland of human heads around her neck. Each of her hands holds a different object that symbolizes the different parts of her. Kali holds the abhoy-mudra in her upper right hand and the baroda-mudra in her lower right hand. Mudras are the way that one holds their fingers and hands, and is more widely associated with meditation and spirituality. In her upper left hand, Kali holds a kharga (ax) and in her lower left hand, the head of an asura (demon). Kali’s right hands show her grace while her left hands show her vengeance. The juxtaposition is fascinating, as it shows opposite traits of Kali in the same art form. She is decorated with traditional jewelry, including bangles and jhumka earrings which expose her femininity.

This painting is part of a larger collection of Kalighat paintings in the Victoria and Albert Museum. Kalighat paintings are a genre of painting from 19th century Kolkutta. Kalighat painters, or patuas mass produced these paintings as they were low cost and provided them with a living. Traditionally, Patuas told longer stories through their paintings, resulting in their paintings being over 20 feet long. However, after seeking external inspiration and feeling the need to produce paintings faster, the patuas adopted painting fewer figures with simple colors and backgrounds. With the influx of tourism in Kolkutta, these paintings were purchased by tourists and visitors. However, these paintings were sometimes viewed as ‘oriental’ or ‘exotic’ when brought back to the west. After discussing orientalism and its context in class, I find it interesting to look at the factors and stylistic choices in art that could be manipulated to fit this perspective.

Kali is the goddess of time, doomsday, and death. The origins of Kali can be traced back to deities in the tribal and mountain villages in South Asia. We first see Kali in Sanskrit scriptures in the Devi Mahatmya, which translates to “The Glorifications of the Goddess.” Kali is usually depicted with black or blue skin, like in the painting. She is sometimes portrayed dancing on her husband, Lord Shiva. The Devi Mahatmya tells her story, that she arose from the goddess Durga to kill the demon Raktabija. As Kali is trying to defeat him, each drop of his blood transforms into a new demon. To stop this, Kali licks up the blood before it reaches the ground and turns into a demon. This is why her tongue was dripping with blood in the painting. Kali is known to embody shakti, which is feminine energy, creativity, and fertility. This energy is evident through her actions, power, and visual appearance.

Kali is predominantly worshipped in Kashmir, Kerala, Bengal, Assam, and South India. 20th-century feminists in the US viewed Kali as a symbol of empowerment during their movement. This is an interesting contrast to the way that Kalighat paintings were viewed and understood in the western world, and definitely provides depth to the perception of both Kali and Kalighat paintings.

Saraswati Vina/Veena Instrument

1870-90

South India, possibly Vizagapatam, Andhra Pradesh

Victoria and Albert Museum

Ella Grace Collard

The Saraswati Vina/Veena (or “veena” for short) is one of India’s oldest instruments with a recorded history going back to about 1500 BC. It is named after the river goddess of knowledge, music, art, speech and education. Saraswati’s earliest appearance was in the Rig Veda, yet she remained important well beyond the Vedic period into modern Hindu tradition. Interestingly, she is also recognised by the Jain religion of west and central India as well as some Buddhist sects. The veena instrument is key in almost every depiction of this goddess; over the centuries she is pictured holding many types of veenas. The oldest known carvings of Saraswati playing it were discovered in Buddhist archeologist sites from 200 BC. The veena is believed to symbolize all creative arts and sciences, and when Saraswati plays it, knowledge expresses itself as harmonious music.

Dr. Jayanthi Kumaresh is one of the world’s most famous veena players. Dr. Kumaresh comes from a deep-rooted lineage of musicians who have been practicing Carnatic music for over 6 generations (she started at age 3). She collaborated with the V&A to publish a series of videos depicting her talent and her personal story. In one particular feature, she discusses the history of the famous instrument. The first one was created using a human skull with a bamboo stick attached to it; a gutted nerve was used as a string. A man witnessed a bow and arrow go off in the forest and it was the first ‘twang’ he had ever heard, which led him to attach a total of four strings to the instrument; and that is how the veena came to be. The modern day instrument, no longer using human parts, is made of a variety of different materials like eagle bone, bamboo, wood, and coconut shells. Thanjavur producers in the south of India are considered the most sophisticated makers.

The veena is considered to be a part of the Carnatic music category, which includes the song making and instrumentation of the Southern part of the nation, below the region of Hyderabad (the northern music is called Hindustanic, on the other hand). Yet despite the geographical differences, both schools share two similarities within their practices: the raga and tala. Raga means melody, and tala means rhythm. Musical similarities within India have had a unifying role, historically. People of different backgrounds, castes, status and language come together to enjoy both Carnatic and Hindustanic music; it binded people from a religious and philosophical standpoint. South Asian musical practices have even managed to calm religious-based conflict through its ability to strengthen and expand methods of worship, which brought people together given the idea of possibility. Undoubtedly, religion encompasses one of the largest portions of India’s culture and history. And some would argue that it is impossible to separate music from religion in India, for religious meaning, concrete and abstract, is present in South Asian music at every level. In Hindu metaphysics, for example, sacred sound when organized and articulated as music has the power to represent the order of the universe and by extension symbolically to sustain human existence. Interestingly, the meter (tala) of Indian music presents itself as a series of patterns: smaller patterns are the building blocks of larger ones which makes for a cyclical theme with no clear beginning or end. This symbolizes the cycle of birth and rebirth and a sense of continuation after death. Western music lacks this unique structure of circular patterning, making the tala undeniably unique to India’s culture and religious community.

Clearly, there is much more than what meets the ear when analyzing the Saraswati veena from the V&A museum. Through its unique musical structure and religious connections, the veena embodies the essence of India’s diverse musical and spiritual landscape.

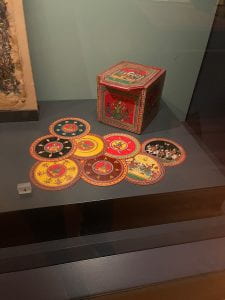

Playing Cards and box for the game of dasavatara ganjifa. Painted and lacquered paper or wood.

About 1900

Maharashtra

Museum – Ashmolean Museum

Isabella Keith

This ornately decorated set of playing cards and accompanying boxes come from around 1900 in the Maharashtra region of India, and are for playing a game called dasavatara ganjifa. This specific set is made from lacquered paper and/or wood and painted. Ganjifa was a traditionally popular game among Indian Kings, courtiers, and commoners and is still played today due to its religious affiliations. Dasavatara ganjifa is a variant of ganjifa played with 120 cards. There are 10 suits of cards, each representing one of the ten incarnations of the Hindu deity Vishnu. These ten suits from lowest to highest are “Matsya (fish), Kuchha (turtle), Varaha (boar), Narsingha (lion, or half-man, half-lion), Vamana (Vishnu as a dwarf, round vessel symbols on cards), Parashurama (axes), Rama (bows and arrows), Krishna (round plates shown), Buddha (conch shells), Kalanki (swords).” Each suit has a corresponding background color and suit sign. Each suit also has 12 cards in it, ten cards being represented by numbers Ace through ten and two cards being represented by court. One is the upper court card or raja, and the other is the lower court card or mantri.

The cards are circular, and the larger the cards the more “subsidiary” figures appear on the raja cards. Scenes depicted on the cards vary, but all show some story or aspect of Vishnu. Some of these scenes include him and Radha standing together beneath a tree or him squirting colored water at the festival of Holi. All the mantri cards will depict one to two riders with occasional footmen or hunters as well. The boxes for the cards are cubic and decorated similarly to the cards, decorated on all sides with scenes of Vishnu. The artists responsible for the making of the card sets are largely unknown, as most cards are made anonymously, but a few workshops have been recorded and some modern packs will have the painters’ initials painted on them.

All cards are made in very bright colors and will be thin and flexible. They come in many varieties of quality, making the game accessible to many different people in different social and economic classes. The cards also come in a variety of sizes, ranging from diameters of 55 cm to 112 cm. As for the boxes, most boxes made prior to 1875 will have a tongue on the lid, while many boxes made post-1875 are square. This particular box from the Ashmolean Museum is dated around 1900 but has a tongued lid, which does not fall exactly in line with this pattern.

This game is typically played in the evening using a white cloth on a flat surface. The cards will be shuffled on the cloth face down before being divided equally among the players, usually three or four people, and the player with the “highest denomination” has the first turn. The game is played counter-clockwise and the goal is to gain the highest number of cards by the end of the game. In each round, the goal is to play the card with the highest denomination. A card’s denomination is determined by its suit and numerical value or court. The game requires players to remember the suite and number of each of the cards played in that round, and the corresponding denomination for each card in order to win, strengthening a player’s memory.