Posts in Category: Uncategorized

Land use, fire, and climate contributed to deforestation on the Pacific Islands

Three thousand years ago, human colonists encountered islands in remote parts of the western Pacific (Remote Oceania) for the first time. The deforestation and ecosystem degradation that followed is often attributed to human land use and exploitation. This interpretation has become a modern environmental parable about the inevitable negative ecological impacts of human activity. However, as awareness of the role of climate in shaping ecosystem vulnerability has increased, we wondered if Pacific Island deforestation could be associated with the influence of both climate and land use. Archaeological findings indicate that the first settlers in Remote Oceania were farmers who brought with them domesticated plants and animals as well as slash-and-burn farming techniques1; therefore, land use and fire were primary mechanisms capable of driving deforestation. However, the role of climate and fire–grassland feedbacks in driving deforestation in the region is poorly understood.

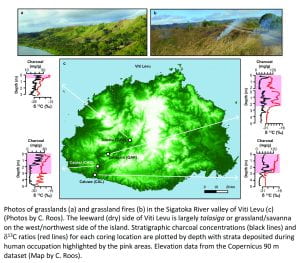

To investigate the influence of El Niño droughts on fire activity and deforestation before and after settlement, we used a landscape geoarchaeology approach to reconstruct the fire and grassland history on the leeward (dry) side of Viti Levu, Fiji, the fourth largest island in Remote Oceania (See above). Terrestrial soil cores were obtained from small watersheds that are tributary to the Sigatoka River. We used sedimentary charcoal and stable isotopes of soil carbon from these samples to reconstruct fire and grassland abundance across roughly 600 km2 over the past 7,000 years andcompared these records with El Niño frequencies recorded in lake sediments at Laguna Pallcacocha, southern Ecuador.

We found evidence of small fires and minor representation of grasslands before human settlement occurred roughly 3,000 years before present (yr BP). Following human settlement, charcoal and isotopic signatures of grasses increased dramatically, which appears to confirm the idea that human land use drove the deforestation of Pacific islands. However, comparing these fire and grass histories to regional charcoal records as well as proxies for El Niño drought frequencies indicates that fire and grass dynamics were shared across the region, corresponding to increasing periods of drought. These findings suggest that the climate could also be a plausible cause of deforestation by driving fire and grassland expansion. Given the human history of Remote Oceania, it is likely that climate variation enhanced the vulnerability of Oceanic forests to fire and conversion to grasslands or, that human activity enhanced the climate vulnerability of these ecosystems.

Our work highlights the complex relationships by which human land use, fire, and climate interact. In some cases, human activities (such as active fire management) can reduce the influence of climate on fire activity. In other cases, human activities such as deliberate or accidental burning can amplify the impacts of climate. This historical case provides long-term evidence to support the notion that wildfire management can have an important effect on fire–climate relationships.

You can find the original article here:

Roos, Christopher I., Julie S. Field, and John V. Dudgeon

2023 Fire Activity and Deforestation in Remote Oceanian Islands Caused by Anthropogenic and Climate Interactions. Nature Ecology & Evolution 7:2028-2036. [PDF] [LINK]

Indigenous burning is not easily replaced or imitated

Photo from the Nature Conservancy Australia.

Cultural fire knowledge needs to be supported and preserved where it still exists because the ecological and cultural benefits of Indigenous fire practices are not easily replaced or imitated. My colleagues from the University of Tasmania and I make this argument in a summary of our research* in Arnhem Land in a piece for The Conversation.

* You can find an open access version of our research published in Scientific Reports here: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-022-12946-3

Recent papers (June 2022)

It has been a productive summer so far as collaborations over the past couple of years have yielded several papers. With David Bowman and colleagues, I helped frame an exciting study about the decline of a fire sensitive conifer in the highly flammable North Australia savannas. This paradox (a fire sensitive tree persisting in a landscape with lots of fire) can be explained by the high levels of pyrodiversity created by Aboriginal patch burning. Colonialism arrived to Arnhem Land relatively late but included population displacement (and the removal of Aboriginal fire management) and more recently superimposed institutionalized fire management that has driven this loss of ecological value.

With Grant Snitker and others, fire archaeologists of all stripes, we make the case that archaeologists and fire scientists should be working together to better understand the long, intertwined histories of people and fire.

With Tom Swetnam and Matt Liebmann, I reexamined a number of tree-ring and geoarchaeological fire studies across the Southwest US to look at the consequences of Indigenous population removal and other processes of colonialism on Southwest fire regimes.

Bowman, David M.J.S., Grant J. Williamson, Fay H. Johnston, Clarence J.W. Bowman, Brett P. Murphy, Christopher I. Roos, Clay Trauernicht, Joshua Rostron, and Lynda D. Prior

2022 Population Collapse of a Gondwanan Conifer Follows the Loss of Indigenous Fire Regimes in a Northern Australian Savanna. Scientific Reports 12:9081. [PDF] [LINK].

Roos, Christopher I., Thomas W. Swetnam, and Matthew J. Liebmann

2022 Rebound of Fire Regimes in Southwest US Forests and Woodlands, 1200-1900 CE. In Questioning Rebound: People and Environmental Change in Protohistoric and Early Historic Americas (ed. E. Jones and J. Fisher), pp. 54-65. University of Utah Press. [PDF].

Snitker, Grant, Christopher I. Roos, Alan P. Sullivan III, S. Yoshi Maezumi, Douglas W. Bird, Michael R. Coughlan, Kelly M. Derr, Linn Gassaway, Anna Klimaszewski-Patterson, Rachel A. Loehman

2022 A Collaborative Agenda for Archaeology and Fire Science. Nature Ecology & Evolution 6:835-839. [PDF] [LINK].