Posts in Category: Pyrogeography

Posts on pyrogeography

Culture and anthropogenic fire regimes

Co-author and White Mountain Apache tribal member, Nick Laluk working on a stratigraphic profile in the Forestdale Valley on the White Mountain Apache reservation.

Paleofire scientists often focus on human population size or density to the exclusion of other human variables in the study of human influences on past fire regimes. Here, with colleagues from University of California, Berkeley, White Mountain Apache Tribe, and the University of Arizona, we show that human-influenced fire regimes varied with different cultures of the residents of the eastern Mogollon Rim region of central Arizona. For centuries during Ancestral Pueblo and Apache land use, anthropogenic burning increased burned areas primarily to support agriculture. For centuries under Western Apache land-use, fires were frequent enough to substantially change fuel loads to support hunting, foraging, and pasturage for domesticated livestock.

You can read more in the open access paper in Quaternary Research below.

Roos, Christopher I., Nicholas C. Laluk, William T. Reitze, and Owen K. Davis

2023 Stratigraphic Evidence for Culturally Variable Indigenous Fire Regimes in Ponderosa Pine Forests of the Mogollon Rim Area, East-Central Arizona. Quaternary Research 113:69-86. [PDF] [LINK]

Indigenous burning buffered climate impacts

Fire-scarred ponderosa pine (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The ecological importance of Indigenous burning and fuel management has been much debated, particularly in dry forests of western North America where lightning fire frequencies are high. Using an extraordinary collection of nearly 5000 fire-scarred trees across dry forests and three in Arizona and New Mexico, my colleagues and I were able to assess the impacts of Indigenous fire management by Diné (Navajo), Hemish (Jemez), and Ndée (Apache) people on fire-climate relationships. We show that Indigenous fire management weakened the impact of climate on fire activity at local (stands of a few acres) and landscape scales (100s sq mi).

Fragmentation of fuels by anthropogenic pyrodiversity (a mosaic of many small burn patches) may have weakened the influence of climate on fuel production and drying for fire spread even if the particular cultural and economic purposes of burning that created the pyrodiversity varied across the three different cultural groups. This shows that #goodfire can reduce the impact of climate on fire activity – it did so for centuries in the SW, particularly under Indigenous management.

This study would not have been possible without collaborations with Diné, Hemish, and Ndée communities and scholars. My co-authors and I acknowledge that tribal elders describe deep connections to traditional territories since time immemorial for Diné, Hemish, and Ndée people. Although archaeology and history document varying intensities and locations of land use and settlement, we recognize that Diné, Hemish, and Ndée connections to their traditional territories extend deep in the past and are ongoing.

The original study:

Roos, Christopher I., Christopher H. Guiterman, Ellis Q. Margolis, Thomas W. Swetnam, Nicholas C. Laluk, Kerry F. Thompson, Chris Toya, Calvin A. Farris, Peter Z. Fulé, Jose M. Iniguez, J. Mark Kaib, Christopher D. O’Connor, and Lionel Whitehair

2022 Indigenous fire management and cross-scale fire-climate relationships in the Southwest United States from 1500 to 1900 CE. Science Advances 8:eabq3221. [PDF] [LINK]

Press coverage can be found here:

In Science magazine: https://www.science.org/content/article/indigenous-americans-broke-cycle-destructive-wildfires-here-s-how-they-did-it

In Popular Science magazine: https://www.popsci.com/environment/indigenous-burn-practices-southwest-wildfire/.

In Axios magazine: https://www.axios.com/2022/12/07/wildfires-indigenous-cultural-burning

In Courthouse News Service: https://www.courthousenews.com/native-americans-managed-wildfire-risk-with-controlled-burns-for-hundreds-of-years/

Reimagine fire science for the Anthropocene

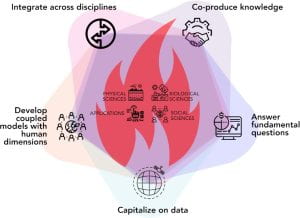

In May 2021, a group of more than 80 fire scientists across disciplines met in a virtual workshop organized by the National Science Foundation's Division of Environmental Biology and Know Innovation. Together, we began to imagine what is necessary for fire science to meet the challenges of the Anthropocene - the new era of human dominance in the Earth System. We identified five major challenges for scientists and funding agencies to address that are encapsulated in this figure.

I was part of the lead authorship team for the synthesis paper published in the open access journal PNAS Nexus. You can read a press release about the paper here.

Shuman, Jacquelyn K, Jennifer K Balch, Rebecca T Barnes, Philip E Higuera, Christopher I Roos, Dylan W Schwilk, E Natasha Stavros, Tirtha Banerjee, Megan M Bela, Jacob Bendix, Sandro Bertolino, Solomon Bililign, Kevin D Bladon, Paulo Brando, Robert E Breidenthal, Brian Buma, Donna Calhoun, Leila M V Carvalho, Megan E Cattau, Kaelin M Cawley, Sudeep Chandra, Melissa L Chipman, Jeanette Cobian-Iñiguez, Erin Conlisk, Jonathan D Coop, Alison Cullen, Kimberley T Davis, Archana Dayalu, Fernando De Sales, Megan Dolman, Lisa M Ellsworth, Scott Franklin, Christopher H Guiterman, Matthew Hamilton, Erin J Hanan, Winslow D Hansen, Stijn Hantson, Brian J Harvey, Andrés Holz, Tao Huang, Matthew D Hurteau, Nayani T Ilangakoon, Megan Jennings, Charles Jones, Anna Klimaszewski-Patterson, Leda N Kobziar, John Kominoski, Branko Kosovic, Meg A Krawchuk, Paul Laris, Jackson Leonard, S Marcela Loria-Salazar, Melissa Lucash, Hussam Mahmoud, Ellis Margolis, Toby Maxwell, Jessica L McCarty, David B McWethy, Rachel S Meyer, Jessica R Miesel, W Keith Moser, R Chelsea Nagy, Dev Niyogi, Hannah M Palmer, Adam Pellegrini, Benjamin Poulter, Kevin Robertson, Adrian V Rocha, Mojtaba Sadegh, Fernanda Santos, Facundo Scordo, Joseph O Sexton, A Surjalal Sharma, Alistair M S Smith, Amber J Soja, Christopher Still, Tyson Swetnam, Alexandra D Syphard, Morgan W Tingley, Ali Tohidi, Anna T Trugman, Merritt Turetsky, J Morgan Varner, Yuhang Wang, Thea Whitman, Stephanie Yelenik, and Xuan Zhang

2022 Reimagine fire science for the anthropocene. PNAS Nexus 1(3):pgac115. [PDF] [LINK].

Indigenous burning is not easily replaced or imitated

Photo from the Nature Conservancy Australia.

Cultural fire knowledge needs to be supported and preserved where it still exists because the ecological and cultural benefits of Indigenous fire practices are not easily replaced or imitated. My colleagues from the University of Tasmania and I make this argument in a summary of our research* in Arnhem Land in a piece for The Conversation.

* You can find an open access version of our research published in Scientific Reports here: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-022-12946-3

Utah State University Ecology Center Seminar series

I recently had the pleasure of visiting Utah State University, where I gave two talks as part of the Ecology Center Seminar series. You can catch both talks below as well as a short radio interview that I did for the local NPR station.

Check out the NPR interview here.

High-severity fires and shrubfield establishment (new paper)

Fire is an important part of maintaining some ecosystems but it can also be a catalyst for change. An illustration of this are the small but persistent shrub patches that dot pine forests across the Southwest US. These shrub patches were created by high-severity fires that killed the canopy, thus allowing resprouting species, such as Gambel oak to establish. But just how long these shrub patches can persist has not been clear.

Chris Guiterman and I used tree-rings and soil charcoal to identify the timing of high-severity fires that established three of the largest shrub patches in the Jemez Mountains of northern New Mexico. You can read more about it here.

Video of Southwest Fire Science Consortium webinar

The Southwest Fire Science Consortium webinar that I co-lead with Chris Toya and John Galvan from the Pueblo of Jemez Natural Resources Department is now available to stream on Youtube. Here I lay out the science and traditions behind centuries of sustainable Jemez (Hemish) fire management before Spanish colonialism. Chris and John put this in a cultural and contemporary context.

SW Fire Science Consortium webinar at noon MST on March 4, 2021

Come see me at the March 4 SW Fire Science Consortium webinar (noon MST). With colleagues from Jemez Pueblo, I will be talking about lessons for coexistence with wildfire from Native American fire management at an ancient wildland-urban interface.

March 4, 2021: Native American fire management at an ancient wildland–urban interface

Native American fire management at an ancient Wildland-Urban Interface

As residential development continues into flammable landscapes, wildfires increasingly threaten homes, lives, and livelihoods in the so-called ‘wildland-urban interface’ or WUI. Although this problem seems distinctly modern, Native American communities have lived in WUI contexts for centuries. When carefully considered, the past offers valuable lessons for coexisting with wildfire, climate change, and related challenges. Here we show that ancestors of Native Americans from Jemez Pueblo used ecologically savvy intensive burning and wood collection to make their ancient WUI resistant to climate variability and extreme fire behavior. Learning from the past offers modern WUI communities more options for addressing contemporary fire challenges. Public-private-tribal partnerships for wood and fire management can offer paths forward to restore fire-resilient WUI communities.

I recently published an interdisciplinary paper in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that documents centuries of sustainable wood and fire use by Hemish people (Ancestral Pueblo) in the Jemez Mountains of northern New Mexico. You can find the article here or on my publications page.

Roos, Christopher I., Thomas W. Swetnam, T.J. Ferguson, Matthew J. Liebmann, Rachel A. Loehman, John R. Welch, Ellis Q. Margolis, Christopher H. Guiterman, William C. Hockaday, Michael J. Aiuvalasit, Jenna Battillo, Joshua Farella, and Christopher A. Kiahtipes (2021). Native American Fire Management at an Ancient Wildland-Urban Interface in the Southwest United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118(4): e2018733118.

What impact has fire suppression had on wildfire intensities?

Pinyon, juniper, and ponderosa pine trees killed by the 2012 San Juan prescribed burn at the archaeological site of Wabakwa in northern New Mexico. Photo by C. Roos.

Many tree-ring and charcoal studies indicate that the period of fire suppression (the last 120+ years) is unique for its paucity of fire over multi-century to multi-millennial timescales in dry forests across the Western US. Nevertheless, there are still some scholars and environmentalists who suggest that fire behaviors (for example, fire intensity, or temperature for a given area) and impacts (for example, fire severity, or the degree of above ground biomass consumption or mortality) in modern fires that follow that fire free period are within the historical range of variability for the West. Tree ring and charcoal methods are generally unable to get at fire intensities of the past to evaluate the uniqueness of fire intensities from fire suppression and fuel accumulation today.

With colleagues at Utah State University, the University of Arizona, the US Geological Survey, Southern Methodist University, and Harvard University, I have just published an innovative application of archaeological luminescence dating to assess the consequences of fire suppression and fuel accumulation on fire intensity relative to a millennium or more of frequent surface fires. By using the heat sensitive luminescence signal from archaeological ceramics exposed to historical surface fires (documented in tree-ring records) and those exposed to a 2012 prescribed burn under mild weather conditions, we were able to isolate the impact of fire suppression-generated fuel buildup on fire intensity. All ceramics burned in the 2012 fire with modern fuels had their luminescence signal reset, indicating that they were heated high enough and long enough to free electrons from crystaline traps and reset the luminescence clock. In contrast, none of the ceramics exposed to at least 14 historically documented surface fires had any evidence of resetting, indicating that fire intensities (and duration) in modern fuels had no precedent since at least before the site was established roughly 900 years ago.

Add climate change to the scenario and the combustible situation with modern fuels requires urgent action.

This paper was published in the open access journal Fire. You can find the article here or here.

Roos, Christopher I., Tammy M. Rittenour, Thomas W. Swetnam, Rachel A. Loehman, Kacy L. Hollenback, Matthew J. Liebmann, and Dana Drake Rosenstein

2020 Fire Suppression Impacts on Fuels and Fire Intensity in the Western US: Insights from Archaeological Luminescence Dating in Northern New Mexico. Fire 3:32.