On the eve of the United States’ Centennial Year, a notable number of people “made it their especial business to hear the New Year’s bells” at New York City’s Trinity Church. When the church opened its doors an hour before midnight December 31, 1875, the pews filled to capacity, leaving the aisles crowded with men and women. Throngs jostled on the steps of A. T. Stewart’s “Iron Palace,” the nation’s first and most fabulous department store. Crowded carriages stood along both sides of Broadway for several blocks between Ninth and Eleventh Avenues. Thousands of the city’s million residents clustered in and around its most prominent church, not for the sermons and dispensations, but to enjoy a carillon bell concert, whose program was inflected with patriotic songs, including “Yankee Doodle” and “Hail Columbia,” and to hear the time bell ring in the New Year, after which the crowd dispersed with little ado. Assembling in churches on New Year’s day to hear sermons and dispensations was a long-lived practice; but when Trinity Church’s Neo-Gothic tower and spire were completed in 1846, it more so than any other church in the nation’s leading city became the focal point of New Year’s Eve festivities. Over the course of the nineteenth century, New Year’s observances shifted from the first day of the New Year to the eve before, due to a number of technological developments, not the least of which was precision timekeeping. Paradoxically, the New Year’s crowds that gathered in and around Trinity Church during the second half of the nineteenth century presaged the end of American churches’ monopoly over the grandest of all temporal rites, New Year’s observances.

For millennia prior to the nineteenth century and in places across the world, temporal rites were intimately associated with religion. Many of these rites were associated with calendars, whose computation was charged with religious meaning and significance. None were more important than the observances associated with the arrival of a New Year, whether in Christian Europe, among Jews in many lands, across the Chinese empire, or in Mayan city states. Since the thirteenth century, when mechanical clocks slowly began to introduce another way besides the calendar to mark the passage of time, religious authorities tried to assert control over clock time. Despite their early incidence in monasteries, where clocks helped inhabitants routinize their rounds of prayer and devotions, clock time stood apart from religious rhythms and precepts. No religious temporal rites developed to smooth the way for the hegemony of the clock. Churches across Europe and the United States appropriated clock time by installing enormous clocks and heavy time bells on their towers. But eventually other social authorities assumed the responsibility for dispensing the time, largely by implementing scientific and technological procedures that guaranteed greater synchrony among communities.

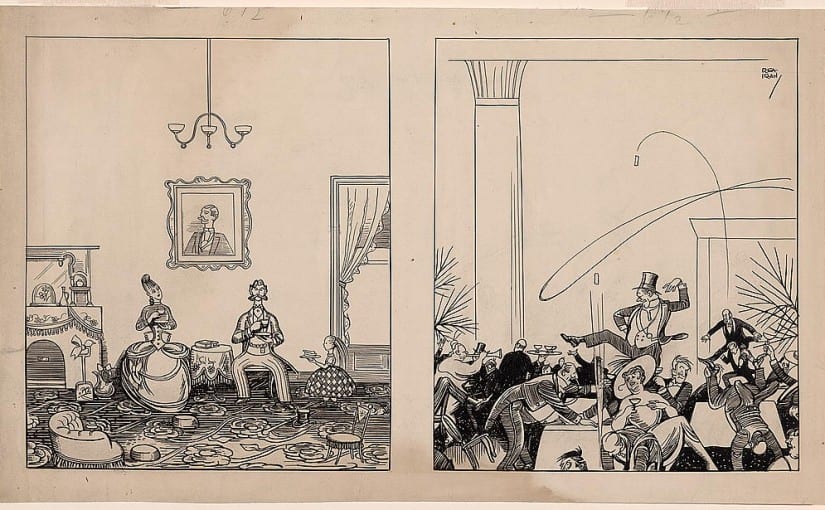

Indeed, not long after the introduction of standard time and time zones in the United States on November 18, 1883, Trinity Church’s centrality to heralding the New Year was eclipsed. On the night of December 31, 1883, pandemonium characterized the vicinity of Trinity Church. Even though police confiscated tinhorns and bladders devised to make loud noises, “the noise of a thousand horns made night hideous and the sound of chimes inaudible.” With each year, ever larger and louder crowds assembled near Trinity Church to greet the New Year: but no one could hear the chimes. The din was so tremendous that, according to the New York Times, it was “impossible to hear even the sounding of the hour of 12 by the ‘Great Tom,’ the mammoth of the chime of bells.” So, in 1893 in the feeble attempt to discipline the crowds, Trinity’s rector Reverend Dr. Morgan Dix announced that the church’s bells would be silent when 1894 arrived. A January 1, 1894 headline read: “Bells Gave No Welcome.” As Reverend Dix explained, the crowds of noisy and rowdy people “who failed to appreciate the sacredness of the time” forced him to silence Trinity’s bells. Although the New Year was a civic holiday – neither Protestant nor Catholic Church has a rite devoted to sanctifying the New Year – the Reverend Dix associated it with the opportunity to acknowledge God’s gift of time, and the Biblical mandate to “redeem the time” (Ephesians 5:16).

Perhaps sensing that he, and the church as a whole, was losing the battle to keep New Year’s observances sacred, the Reverend allowed Trinity’s bells to chime when 1895 arrived despite the prospect of bedlam. But the chimes were yet again impossible to hear, due in part to “boys [who] made the night hideous with their horns and whistles.” Simultaneously, fireworks around City Hall drew revelers away from Trinity Church’s environs. As the city became ever louder, fireworks had the advantage over bells of being visible signs of midnight’s arrival. In 1905, the New York Times entered the fray, offering a fireworks show from atop its newly constructed Times Building in Longacre Square, soon to be rechristened Times Square. But pyrotechnics were both dangerous and inexact: an era of precision timekeeping required a visible indicator that the New Year had begun. Large clocks whose works were far from their faces and whose hands were subject to the elements were unreliable, but a time ball seemed to promise the magic, precision, and visibility the age demanded. So beginning in 1908, and lasting for more than a century since, there has been no need to silence the crowd: instead a magnificent illuminated ball glides down a pole atop One Times Square, visible to the hundreds of thousands of merry makers gathered below and the millions more watching television. The chimes of Trinity Church, and the sense of the sacredness of time, receded ever more, as did the church’s monopoly over temporal rites.

Copyright 2015 Alexis McCrossen. Please do not cite or quote without author’s written permission. For permission, please email amccross@smu.edu.