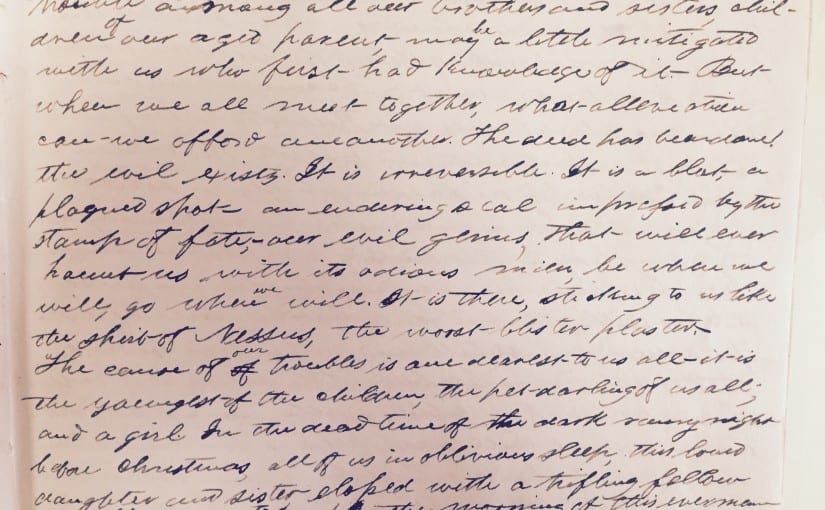

While transcribing entries from the private journal of a lifelong resident of North Carolina, William D. Valentine, I came across an 1845 entry that began, “Yesterday Christmas that holy anniversary of our Lord’s birth…” But instead of an account of merriment, prayers, and presents for the children, Valentine fulminated for pages that “it will long be remembered as a day of sorrow mingled with indignation and mortification–a day of deep seated family affliction and trouble… We went no where; we wanted to see no person…. The only relief was now and then a tear from father or brother.” As I tried to make out the handwriting, my mind leapt around, first to a death, but then to a row, or perhaps an arrest, a bankruptcy? Then I reached the bottom of the page, where Valentine recounts the elopement of his sister Christmas eve with “a trifling fellow.” The rest of the Christmas season Valentine found himself unable to accept his sister’s marriage: he wrote a few days later, “the affair has disturbed my peace more than any thing that ever occurred in our family.”

And yet, Valentine’s diary is full of holiday sadness, for himself, for his family, and for his nation. In 1841 he writes “this has not been a very merry Christmas.” On the last day of the next year the young lawyer Valentine writes “This being the last day of this any thing to me than agreeable year.” Even before his sister’s seduction Valentine was apparently mortified: in accounting for 1842 he reflects that, “most of the time I spent in pain , penury and mortification.” The 1844 holiday season was especially rough: not only does Valentine complain about being unmarried, his 1845 New Year’s day entry recounts in sad and perhaps even paranoid detail the election of James K. Polk to the Presidency: “The past year, the eventful 1844, is gone and these good friends of the country are in deep heartfelt sorrow.” Not that long afterward was “a year of war and rumors of war,” so much so that 1847 “entered with the blast of war.”

One more sad thing leaps out from Valentine’s private journal, a portal into the many sad things that happened during holidays past. On January 1, 1851 Valentine complained that “a most disagreeable but necessary duty devolved on the heads of this family yesterday.” Several of his slaves stole and slaughtered a neighbor’s hog, so “we tied them up and whipped them.” Many other entries note attending “the Negro hire” around the turn of the year, which reminds the reader of Valentine’s diary that while the sudden departure of some members of a household (like Valentine’s sister who eloped with that trifling fellow) led to mortification, other sudden departures, like the rental and sale of slaves, did not even merit notice in the annals of holiday remembrances like Valentine’s. And yet, what Valentine wrote the day after his sister eloped could well be appropriated to describe the feelings and experiences of countless Americans: “it will long be remembered as a day of sorrow mingled with indignation and mortification.” For example, William Nell, the first African-American to work in the Federal government, described New Year’s day as being “proverbially known throughout the South as ‘Heart-Break Day,’ from the trials and horrors peculiar to sales and separations of parents and children, husbands and wives” (1863). Heart-break Days indeed.

Sources: William Valentine’s private journal is held in the Southern Historical Collection at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. My thanks to David Henkin for bringing to my attention William Nell’s condemnation of New Year’s Day in the antebellum South in an 1863 speech celebrating the Emancipation Proclamation.

Copyright Alexis McCrossen November 12, 2015. If you’d like to circulate, quote at length or reprint this post, please email me first at <amccross@smu.edu> . Thanks.