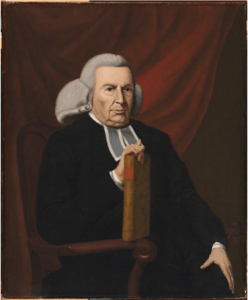

Charles Chauncy (1705-1787)

By: Lindsay Bellack

In order to properly understand what the opposition to the Great Awakening looked like, it is important to understand what the Great Awakening was. The Great Awakening was a religious revival that swept over British America in the early eighteenth century. The Great Awakening caused a lot of controversy with many opposed to the new religious ideals and many more that were willing to practice. The chief tributaries were Continental Pietism, Scots-Irish Presbyterianism, and Anglo-American Puritanism.

Charles Chauncy (1705-1787)

The Great Awakening altered the religious practices of the general population by taking the focus away from a repeated ritual as a way to foster a more personal experience. The idea was to hold you more accountable for the efforts you put into your faith. It fostered a deeper spiritual connection between the average person and their faith. A number of preachers were involved in spreading this new approach to religion; they had a great impact on many, this included not only those originally from Europe, but the Native Americans, freed blacks, and slaves. A great deal of the population converted to Christianity to join the revivalist movement

For my map, I focused on influential preacher and writer, Dr. Charles Chauncy(1705-1787). Chauncy was the grandson of well-known British immigrant, preacher, and former president of Harvard, Charles Chauncy (1592-1671). Dr. Chauncy was born and raised in Boston, MA, where he spent the majority of his life. He was the resident preacher at the First Church of Boston, where he spoke out against the Great Awakening, or, in that time, referred to as the revivalist movement.

First Church Boston

Although Chauncy was mentioned in some correspondences elsewhere, his well-known influential actions were done either through his preaching in the First Church of Boston, or through his various sermons published and advertised in many newspapers around the New England area. Chauncy’s main work began in the early 1730s when he really came into his own in terms of his beliefs.

Chauncy was a very strong force opposing the Great Awakening, and was frequently there to combat the concepts revivalists were attempting to spread in New England. The revivalists’ growing presence in New England, especially George Whitefield, were the reason behind why he became so outspoken on the topic.[1] He believed that their new concepts promoted enthusiasm. The idea behind Religious Enthusiasm is that it promoted women to become more actively involved in the church, and seeing as how women at the time having any involvement in anything beyond their family and their duty to their husbands was controversial, their increased hands on involvement in the church caused many individuals to be taken aback.

Chauncy’s sermons were known to be very powerful and held very strong and firm beliefs. Something that I highlight in my map is Chauncy’s transition from an Anglican to a Calvinist in the mid 1740s. Despite his change in viewing his faith, he still maintained a strong opposition toward the revivalist movement. As mentioned earlier, Chauncy was firmly opposed to religious enthusiasm, and that is highlighted in one of his more famous sermons, A Caveat against Enthusiasm. In his sermon, he highlights the nature and influences of enthusiasm. [2]

Sermons like A Caveat against Enthusiasm are a good representation of what led to his later sermons that were rooted in a similar theme but had a more intense tone. It led to his series Five Sermons, which include anti-revivalist sermons like “Breaking of Bread” and “The New Creature describ’d.”

Chauncy also held a position in society where he had both a very great following that supported his ideas and his resistance to the revivalist, as well as an opposition that frequently challenged him and accused him of publishing falsehoods in his writings. Upon closer examination, the New York Gazette could be viewed as one of Chauncy’s opposing forces. As illustrated in one of my map points, In 1768, an anonymous writer for the New York Gazette published an article about Chauncy accusing him of deceitful writing.[3] In this instance he was being accused of publishing false information about the Candidates for the Holy Orders of England. These instances of Chauncy’s published works being criticized were not all that uncommon, and there are other articles similar that criticize his beliefs and his resistance to the revivalist movement.

Charles Chauncy was a very influential figure in the opposition against the Great Awakening. He is an important person to look at in order to understand all aspects of the Great Awakening. Looking only at what those who believed in the Great Awakening gives a very one sided explanation, and understanding why Chauncy opposed the movement is very crucial when trying to grasp a full view of the era.

Further Reading

Sources

Early American Imprints. Five Sermons: “Breaking of Bread”

Conservative Revolutionaries: Transformation and Tradition in the Religious and Political Thoughts of Charles Chancy and Jonathan Mayhew

America’s Historical Newspapers: New York Gazette and Weekly Post-Boy

Early American Imprints: A Caveat against Enthusiasm

Notes

[1] “Whitefield’s first arrival in Boston on September 17. 1740, which seem to have led Chauncy from initial silence through critical questioning to outright opposition to the perceived excesses of the Great Awakening”

– Conservative Revolutionaries: Transformation and Tradition in the Religious and Political Thoughts of Charles Chancy and Jonathan Mayhew

[2] The word is more commonly used in a bad sense, as intending an imaginary, not a real inspiration: accor|ding to which sense, the Enthusiast is one, who has a conceit of himself as a person favoured with the extra|ordinary presence of the Deity. He mistakes the work|ings of his own passions for divine communications, and fancies himself immediately inspired by the SPIRIT of GOD, when all the while, he is under no other influence than that of an over-heated imagination.

The cause of this enthusiasm is a bad temperament of the blood and spirits; ’tis properly a disease, a sort of mad|ness: And there are few; perhaps, none at all, but are subject to it; tho’ none are so much in danger of it as those, in whom melancholy is the prevailing ingredient in their constitution. In these it often reigns; and some|times to so great a degree, that they are really beside themselves, acting as truly by the blind impetus of a wild fancy, as tho’ they had neither reason nor understanding.

-Early American Imprints: A Caveat Against Enthusiasm

[3] The Doctor [Chauncy] has acted altogether beneath the Character of an honest Man; and has thus laid himself open to much Centure and Reproof, that whatever he advances for the Future, must rather deserve than promote our Interest.

–America’s Historical Newspapers: New York Gazette and Weekly Post-Boy