Introduction

Throughout most of world history, railroad progress in developing nations was a precursor for mass industrialization, urbanization, and national progress. When the United States completed construction for the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869 it was able to transport goods and people faster and cheaper becoming the backbone to American economic growth. The cases were different in Colonial India and Porfirian Mexico. Great Britain exploited Indian resources and people so extreme that it deprived the indigenous people of almost everything (including the laborers). In Mexico, characters of its experience with colonialism became the product of railroad development by hurting the peripheries of Mexico. Railroad development ultimately led to underdevelopment in both economies due to over dependence on foreign players.

Photographs taken during this period (1870-1910) provide unique evidence of the experiences of people during that time. In fact, they are underrated resources. Unlike textual accounts, visual evidence like photographs and film footage give the viewer an experience of seeing the events rather than interpreting what happened through writing. Put in another way, visual accounts let the events in photograph do the talking. Reading about wars in books informs the reader about what happened. Seeing a photograph or film footage of war shows perspective, an experience of what historically happened. In a way, the future of history will be defined by visual culture. With 21th century technology (and the underestimated power of camera phones) historical events will have either been caught on video or at least been photographed.

Railroad Construction in India

British imperialism in the 19th century in many ways shaped the world as it is today. Out of all of Britain’s colonies, India unfortunately endured one of the longest and somewhat most recent subjects of Great Britain’s imperialism. For Britain, India was too valuable of a colony to give up—the economic contributions from India were insurmountable. India did provide abundant natural resources—exporting steel goods, iron, and, famously, textiles. However, it can be argued that the major dividends were paid by cheap Indian labor and economically depriving the people, or a captive economy. Britain was also obsessed with everything to do with trains. India’s captive economy, combined with a British imperial railway only intensified the hegemony of the British Raj.

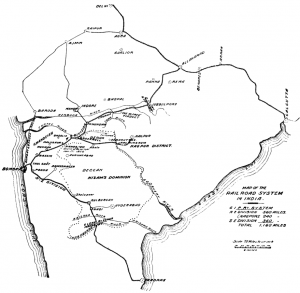

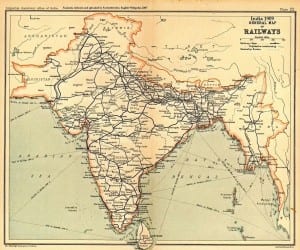

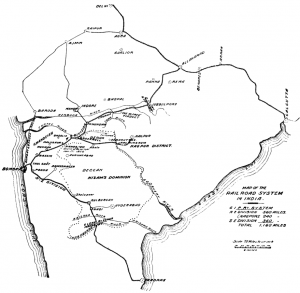

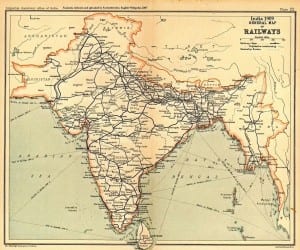

India Railways in 1870. Source: Wikipedia

Indian Railways in 1909. Source: Wikipedia

The British-Indian Railway played a crucial role during the British Raj. It began in 1853 with a short 20 mile rail from Bombay to Thana and by 1900 constructed over 24,000 miles of tracks.1 Private British investors financed the construction of these railroads for the purpose of intensifying Britain’s colonial presence in India. In fact, if the railway investment did not make profits, the colonial government would pay the difference under the guarantee system.2 Who really pay the difference? The working Indian taxpayers of course! The colonial government would increase lagaan (imperial tax) specifically to meet the needs of the companies—the guarantee to pay railway companies’ profit deficits.3 Basically, a portion Indian railroad laborers’ take-home-pay would go back into the pocketbooks of private British investors.

The British-Indian Railroad labor system was organized in a way to prevent Indian workers to rise in the ranks of management. Great Britain would import British engineers and appoint white supervisors to do the “mental work” while they delegated the manual labor and low-personnel jobs (such as engine drivers or guards) to the Indians. They organized Indian workers into labor group “gangs,” headed by an Indian mistri, or the “gang master” under supervision of white upper-management. During railroad construction, the untouchables (who are so low in society that they are outside the caste system) would often do the most dangerous assignments while the rest would do the “not that dangerous” labor.

Labor on the railways was not strictly male, women and even children worked on the construction of British-Indian railways in the late mid to late 19th century. In particular, these peasant families, the “waddars,” came from rural areas to work as the railway diggers and earthmovers.4 Waddars’ were so heavily used by the railway companies that they moved their entire families. Indian labor families were at the mercy of railway companies. The railway companies provided housing for the employed families while paying cheap wages. These waddar families would become overly dependent on company housing and income because the British companies, with the help of the colonial government, strategically obstructed Indian advancement in employment ranks.

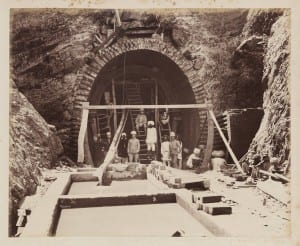

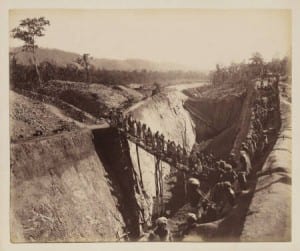

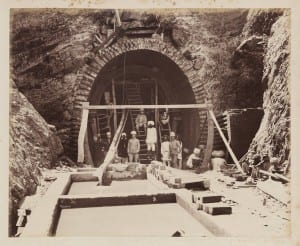

Figure 1. Constructing a tunnel on Bengal-Nagpur Railway (1890)

This photograph (Figure 1) was taken in 1890 and shows the construction of a tunnel part of the Bengal-Nagpur Railway in the mountains (if they weren’t in the mountains then they would not be constructing this tunnel). In the photograph, there are four British “supervisors” and thirteen indigenous laborers indicated by their white or dark turbans. This photograph provides vivid authentic evidence of the power of British colonial presence in the railway system.

Racial economic inequality and living standards gap between the Indian workers and British engineers/officials is extremely vivid. Looking at the difference in clothing distinguishes the (white) skilled workers and (Indian) unskilled workers. Look at the clothing to distinguish white officers from the white engineers. The two British officers overseeing this specific tunnel construction are indicated by the iconic pith helmets. On the far left side, the two men (one has a mustache) are unquestionably imported English civilian engineers. This is proven by two things: simply, the two men are not wearing the British officer uniform (no pith helmet either) and their position is closer to the railroad work than the British officers (who are obviously “supervising” the construction site).

The Indian workers’ clothing indicates them as the manual laborers, especially whether or not they have footwear. In the middle of the photograph the Indian laborer, perhaps the mistri, is wearing shoes. Now looking inside the tunnel, the two Indians laborers sitting on the ladders are not wearing shoes, which could be indicating the men as “untouchable” (since untouchables were too poor to afford shoes). Also note that those two are the only works inside the tunnel. At this site, somewhere in the mountains of India, the most dangerous job is undoubtedly inside the tunnel where worker accidents were rampant.

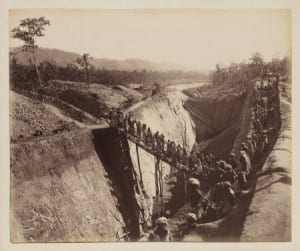

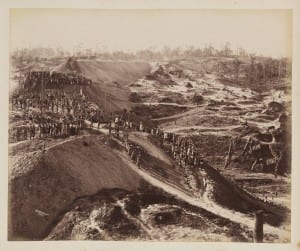

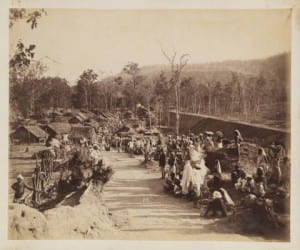

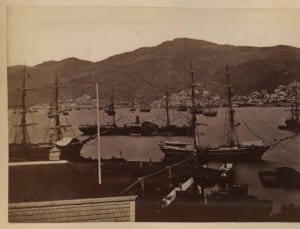

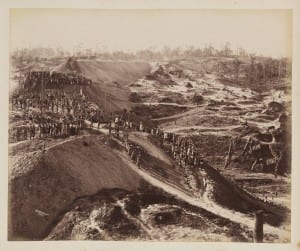

Figure 2. Excavation on the Bengal-Nagpur Railway (1890)

Figure 2 shows a panoramic view of, again, the Bengal-Nagpur Railway. The most striking feature in this photograph is the magnitude of labor the British exploited. This picture could be the poster-child of colonial railway labor; it has almost every character of British colonial rule. One indication of this is the set of tents in in the background (top right). This is none other than a labor camp on the site. Since the picture shows the excavation phase of construction which proves that the masses of people in the photograph are waddars.5

Looking closer to the people, you will find that most of the laborers in this picture are women and children. Out of what appears to be hundreds of workers, about 70% are women and children. They appear to be transporting water by carrying bowls on their heads. This also shows the lack of technology in Indian railway construction. Cheap labor was always readily available that companies would neglect spending on advanced tools (Remember this is in 1890; advanced tech was available and the Industrial Revolution had already occurred in the United States). It goes again to show the neglect and hegemony of the British colonial rule in India.

Railroads in Mexico During Porfirian Era

In the Profirian Era (1877-1910) Mexico’s railroad narrative was also dominated by foreign investors beginning with the United States. In 1880 the Mexican government, under Porfirio Diaz’s dictatorship, launched its first railroad project followed by others throughout Mexico. It was financed mostly by foreign companies (mostly from the United States; European companies began in the 1890s) while the Mexican government provided subsidies that covered 1/3 of construction costs. The plan was to ignite industrialization, increase living standards of the people, and develop into an independent economy.

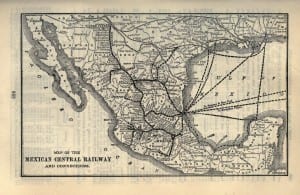

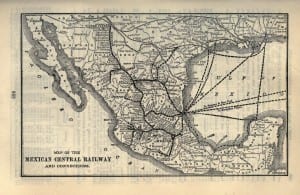

Central Mexican Railroad Map Source: Wikipedia

This did not happen in Mexico. During Diaz, Mexico was experiencing a backward economy that invested too much into foreign contribution and not enough in its domestic production.6 This was very evident in the Mexican railroad business. It became over dependent on foreign (from U.S. and later on European financers) capital investment in the railroad system. It was dominated by foreign money, management personnel, engineers, and even foreign unskilled workers. This foreign dominance in Mexico’s railroad business was purely for the benefit of foreign investors and Profirio Diaz’s government. In fact, the Profirian Mexican government sought to seize private land from its own people to force the development of its railroad system.7

It did not vitalize the Mexican economy. The railroads themselves were constructed with imported rails, locomotives and rolling stock, and even run on foreign fuel.8 Mexico’s economy was largely contributed by exporting mineral and agriculture production goods. The backward economy in Mexico with the contribution of railroads led to many obstacles for the people: low investment on human development, over investment on the export-sector industry (mineral production), foreign capital priority over domestic capital, extreme wealth (land and income) concentration and authoritarian government.9 By neglecting the domestic economic potential, some contributed by the counterproductive effects of railroads, Porfirio Mexico was experienced an underdeveloped economy.

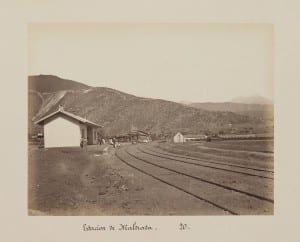

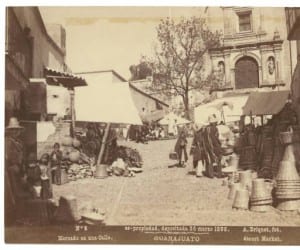

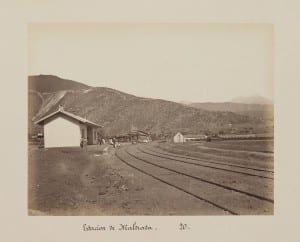

Figure 3. Estacion de Maltrata (1875-1890)

Figure 3 shows a railroad station in Maltrata located in the mountains of southern Mexico during the late 19th century. It gives off a lifeless and lonely vibe. The setting is extremely rural and undeveloped with a railroad station the size of a cabana, a water tank, and two building establishments in the background. It is located in the rural mountains of southern Mexico, which explains the desolateness of the station and the town.

There are also about a dozen Mexican people waiting to board the train. Taken into account that this photograph was taken in the years prior to the Mexican Revolution, it can be inferred that these people are transporting by train to find work and hope. These men have been waiting a long time because it does not look like very many trains pass through this station. There is a man is sitting on the roof of the station who is most likely looking out for an incoming train.

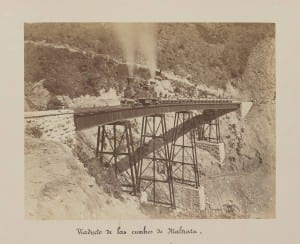

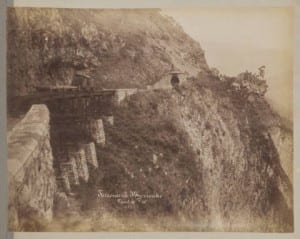

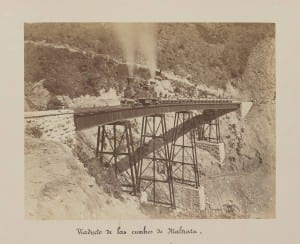

Figure 4. Viaducto de las Cubres de Maltrata (1875-1890)

This photograph shows a railroad viaduct in southern Mexico in the same time period. Again in the mountains so the area is very rural and remote. Riding on the carts are about fifty Mexican men. They are riding the train back from a railroad construction area (those are Mexican workers on the other side of the bridge).

The impact of this photograph is that it shows the railroad labor that some Mexican people contributed. This was by no means a comfortable way of living for any person. It is not good for the people to depend on riding freight to work and if not employed riding the freight to find work in other parts of Mexico.

Conlcusion

Looking through the perspective of the people of India and Mexico involves a different outlook on the impact of colonialism. Colonialism has effected the peripheries of these nations both physically and mentally. The mental impact of colonialism is seen in the post-colonial periods. These times are often filled with wealth inequality, authoritarian style government and leadership, an underdeveloped economy, and underdeveloped people. India and Mexico suffered through these episodes in the years during and following European colonization. The presented photographs confirm these realization by providing the experience of seeing the event rather than interpreting it. Visual culture tells history in innovative and pioneering way that adds emotion and perspective. In today’s camera phone society, everybody has the ability (and arguably an obligation) to document history on Snapchat.

Endnotes:

1 Satya, 69

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Satya, 73

6 Coatsworth, 940

7 Van Hoy, 33

8 Coatsworth, 955

9 Coatsworth, 960

References:

Coatsworth, John H “Indispensable Railroads in a Backward Economy: The Case of Mexico.” The Journal of Economic History. Vol. 39, No. 4 (Dec., 1979), pp. 939-960

Satya, D. Laxman. “British Imperial Railways in Nineteenth Century South Asia.” Economic and political Weekly. Vol. 43, No. 47 (Nov. 22 – 28, 2008), pp. 69-77.

Van Hoy, Teresa M. “La Marcha Violenta? Railroads and Land in 19th-Century Mexico.” Bulletin of Latin American Research. Vol. 19, No. 1 (Jan., 2000), pp. 33-61

Links to Photographs:

Figure 1. http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/eaa/id/1473/rec/9

Figure 2. http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/eaa/id/1506/rec/17

Figure 3. http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/mex/id/1712/rec/1

Figure 4. http://digitalcollections.smu.edu/cdm/ref/collection/mex/id/1715/rec/10

—————

————————————————————

—————

————————————————————