Colonialism is accurately described throughout history as oppression of the worst kind, one where those who are colonized are ruled in their own land and without much of a say in any cultural or legal matters. The colonial histories of India and Mexico, respectively, should be viewed through racial, cultural, and monetary lenses. As Darwinism began to find a foothold in European thought processes, global powers like England and Spain sought to expand their territories through colonizing poorer, ‘effeminate’ countries by exerting power through money and influence. Specifically, England ruled over India through its brokering with the East India Company in an attempt to take advantage of the seemingly rich land that they came across in their travels, summarized well by Edward Said in his trailblazing novel on Orientalism: “The Orient was almost a European invention . . . the place of Europe’s greatest riches and its oldest colonies . . .” (Said 1979). Similarly, Spain traveled to Mexico in hopes of discovering the mythical cities that contained power and money they thought they deserved. Through colonization, Mexico and India were oppressed, but at the same time, they learned valuable lessons that eventually became the foundation of their individual quests for full autonomy. As the decades passed by, the two colonies eventually found power and innovation in themselves, realizations that would have most likely never occurred had they ruled themselves freely throughout history. Evidence of these progressions, via photographs and beginning with the Industrial Revolution, throughout history provides the reader with proof of advances in technology and infrastructure, along with images of actual emotion stemming from social injustices, that are vital to the present day cultures established by both former colonies.

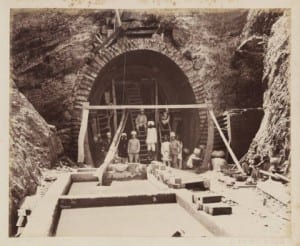

The Indian Ocean World, before the introduction of trade companies and capitalism, was a vibrant part of the world, full of wealth agriculturally, culturally, and in textiles as well. Much to the chagrin of native Indians, those very attributes would attract European powers seeking to expand their spheres of influence and increase national wealth as well. Specifically, around the middle of the 19th century, an idea coined ‘The Great Divergence’ was set in motion and defined the next century for Europe and Asia. Europe, especially the British, began to move towards industrialism through advances in technology, while Asia, namely India, did not. Fueled by exceptionalism and Eurocentrism, the British were able to exert more influence over the Indians as they obtained more powerful guns and access to non-traditional effects not seen before in India: “Europe’s economic progress was outstripping that of the rest of the world so that it had become the clear economic leader well before the Industrial Revolution . . .” (Studer 2008:393). However, because of this clear divergence in progresses, one can argue that India benefited greatly from the period of British oppression. The photo of the Indian and British workers constructing the Bengal-Nagpur Railway provides evidence of the first industrial progress in India, confirmed by M.S. Rajan: “There was a strong reaction . . . in India . . . a reaction which stimulated a renaissance in Asia. . .” (Rajan 1969:90). The construction of this railway eventually led to its assimilation into the Great Indian Peninsula Railway, and then the Central Railway seen throughout India today. Commissioned by British Parliament in contract with the East India Company, the railway might have initially benefitted the English in their pursuit of global influence, but the native Indians are the people who now reap the rewards of industrial progress. The construction of railways produced a price divergence in India alone, seen in the grain market through large price increases and, therefore, greater profits for the native Indians. Without being forced to construct railways in the first place, India might have never achieved the industrial progress seen in their quest to achieve independence.

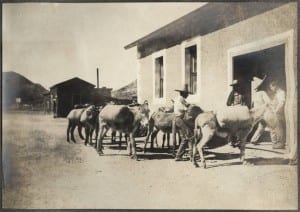

Similar to the plight of India, Mexico experienced a period of colonization by the Spanish empire after their journey for riches in the New World quickly turned into an easy path through Mexican territories of conquering and destruction. The entire goal of the conquests to the Mexican Southwest centered around the riches hidden in the cities and the lack of Western faith in those lands. The friars were sent directly by the Crown to go into those Mexican cities and convert any non-believer to their esteemed religion. However, those friars would encounter a few different types of Mexicans that made their enterprise very difficult. The ‘friendly’ Mexicans were of no trouble, and the Tlaxcalan tribe even aided in the attack on Tenochtitlan. The ‘hostile’ and ‘sullen’ Indians proved tougher to deal with, especially the sullen ones when it came to the spiritual conquest. Instead of directly attacking their ‘teachers,’ the sullen Indians would just discretely disobey the friars, thus making it extremely tough for them to achieve their goal of mass conversions. Although the British and Portuguese were not enforcing religion on the Oriental Indians, they had to be thankful that they were dealing with ‘sedentary’ Bengali. The rebuttal of the Spanish conquests by the native Mexicans greatly aided their quest to free themselves of oppression, and eventually spurred an industrial revolution of their own accord—one very similar to the progression of the colonized people in India. The construction of railways in Mexico galvanized the Mexican Revolution that occurred, following the expulsion of the Spanish, as Americans began to infringe on Mexican borders themselves. The picture above, “Ranchmen bringing corn to town on burros,” shows Mexican ranchers having to transport their goods via burros, traveling often from the arid countryside and back to their villages. The construction of the Mexican Railway allowed the natives to efficiently and safely transport their precious goods, including food and crops to sell, through the previously treacherous climate seen throughout Mexico. However, before they reached industrialization, they had to figure out how to properly harness the technological advances seen throughout Europe that had not yet made it to the New World: “Nineteenth-century tourists to Mexico carried away with them the memory of execrable roads and wretched travel conditions” (Pletcher 1950:26). Without the aid of visual evidence of these harsh travelling options available to Mexicans during the middle of the 19th century, one would never know that industrialization was truly necessary. However, the impact of Spanish rule and technology on the Mexicans remains important today. Had the Mexicans not been subjected to the culturally and technologically advanced Spanish, they would not have deemed themselves inefficient with regards to the changing times. More prominent is the fact that burros and antiquated coaches would have remained the norm throughout Mexico, a realization that becomes more damning when considering how divided the Mexican cultures originated as. The eventual unification and independence of Mexico would have never been possible without their introduction to the new technology brought over by the colonizers from Spain.

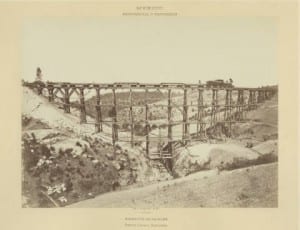

Another important factor in Indian, as well as Mexican, cultural and personal advancement stems from the European based infrastructure. The improved infrastructure, ranging from academia—like the Grant Medical Building seen above, to construction of religious monuments, resulted from the British putting the native Indians to work throughout the colonized land. The building itself clearly shows a European influence in its architecture, and most of Bombay itself became covered in ideals coming from British thoughts: palm trees were planted, the previously mentioned railways, and a focus on improving quality of life are all evident through visual analysis. Specifically, the British seemed to want to provide the opportunity for Indians to learn and, therefore, treat medical problems that arose during colonization. The Grant Medical College, standing tall in stature in the photograph and in its reputation as well, now consistently ranks in the top 10 healthcare centers throughout the world. One must consider that without the British insistence the natives learn about the medical profession, India would not be as well respected as they are today for their contributions to healthcare. While Indian infrastructure facilitated a rise in personal welfare for the country as a whole, the Mexican infrastructure centered around their furthering national industries and the reputations they carried outside of the Mexican borders. Specifically, Mexico saw a rise in the amount of jobs and the specialization increases that accompanied them. However, it must be noted that during, and after, the middle of the 19th century, Mexico was no longer influenced by the Spanish empire; now, they had to prepare themselves for the upcoming border war with the expanding, fledging United States of America. Under the leadership of Porfirio Díaz, Mexico began a period of ‘positivism’ and restructuring of their economy and infrastructure. The foci of this “Paz Porfiriana” centered around cultural stability and improvements in the areas of mines, railroads, and farming. An important photo that provides some context for these advancements is “Viaducto de Jajalpa,” taken by Abel Briquet. This still photograph of a locomotive crossing a ‘viaducto’ in Mexico contains no people, but it contains a deeper meaning nonetheless. In the photo, one clearly sees the steam locomotive and the intricate bride it crosses over. The only action perceived to take place here is the train carrying supplies somewhere important, either for the native Mexicans or for some other purpose. One notable observation that can be made from this photo comes from the idea that this furthers the Mexican industrial progress, making it comparable to India’s industrial revolution. Secondly, one can assume that the locomotive itself was a huge relief in its’ ability to quickly and largely deliver goods from one rural town to another throughout Mexico. The architecture of the ‘viaducto’ is also very impressive, prompting one to both compliment and question the creator of such a project at the time. To conclude, a viewer might ask who did build the bridge—natives or outside influences; as well as asking what the train is actually carrying and for whom. Such a structure became vital in the transportation of coal miners and farmers, as well as the important goods they collected. The construction of a viaduct and implementing a more inter-connected Mexico through railways aided their growth in infrastructure, and was directly impacted by their need to further themselves in the face of an impending border struggle with the United States. The industrialization of India and Mexico allowed both to eventually overcome colonization through social rebellion, acts that were fueled by improved confidence and a newfound sense of nationalism.

Race is an issue that has plagued every civilization, legitimized by the leaders of colonizing societies, and often enraging those affected by it. This theme is exactly what was exhibited in the colonial empires seen in India and Mexico. The colonial revolts that took place in the British-ruled India and the territorially challenged Southwestern United States differed in foundation of ideals, but appear very similar when viewed from a strictly nationalistic point of view. Specifically, both the native Indians and expansionary Hispanics were fueled by their desires to better their peoples and increase the amount of influence they could achieve on their own, goals that were galvanized through decades of colonialism. However, they approach these ends by highly different means. The Indian photo of the Bombay policemen highlights an important idea within their struggle for independence: internal colonialism. The policemen look sedentary and effeminate, falling in line with British portrayals of native Indians. While they may have been given the title of ‘policemen,’ they were really just extensions of British rule within the townships. This idea of internal colonialism remained intact throughout their fight for freedom. Following the Sepoy Rebellion in 1857, the Indians started to establish a precedence for independence; however, Gandhi eloquently summarized their continued plight in the face of increased hope: “. . . India has become impoverished by their Government . . . We are kept in a state of slavery” (Gandhi 27). However, as borders became even more muddled when religious revivalism morphed into dissident factions battling one another. Although the Indians did achieve independence in 1957, they continued to harbor internal colonialism within their communities. The ‘Swaraj’ movement was affected by the disdain shown by the Hindus and Muslims towards each other, a difference not even Gandhi could aid—proven in his eventual assassination by a rivaling RSS group.

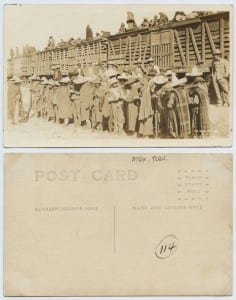

The Hispanic mission did not deal with any religious tensions, per se, but they were very similar to the border-specific battles fought by the native Indians in their colonial revolts. Essentially, the Mexicans saw Texas as its own land and inhabitable by whomever, at a price. They were not saddled by religious problems, but territorial problems. This rivals British views of India as a land in need of governing. The collision course of the American settlers and exploratory Mexicans was inevitable given the respective westward and northern expansions of the two, and began to culminate around the passage of the Adams-Onis Treaty. The United States more than doubled their land claims by acquiring Florida, the Louisiana Purchase, and the subsequent California gold rush. Mexicans could only watch as Americans crept closer and closer to their borders. Fearing huge losses, both territorially and culturally, the Mexicans reacted violently as more Americans came to the ‘Republic’ of Texas, thus beginning the Mexican Rebellion. The photo of Mexican soldiers boarding trains to battle Americans highlights the continued influence of colonialism and the improvements inspired by oppression. Without the trains, the Mexican troops would have continued travelling by burros and other inefficient means. The trainloads of soldiers also furthered ideals of nationalism and hopes for conflict-free lives. However, such a reaction had an inverse effect compared to the Gandhi-led, non-violent Indian rebellions, as it actually inspired Anglo-Saxon nationalism and hurt the Mexican efforts in the long-run, as they eventually ceded Texas to the United States.

The nationalism movements that eventually led the individual colonized nations to independence took different paths, but both were direct descendants of the lasting effects from colonization of Indian and Mexican lands. Evidence of the vital, internal progressions throughout history assuredly give the reader proof of advances in technology and infrastructure, along with images of actual emotion stemming from social injustices. Without the influence and colonization from Spain, Britain, and the United States, Mexico and India would not have reached the cultural and nationalist goals they had to set for themselves.

Works Cited

Andrabi, Tahir and Michael Kuehlwein. “Railways and Price Convergence in British India.” The Journal of Economic History Vol. 70 (2010): 351-377. Print.

Gandhi. Hind Swaraj. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1997. 27. Print.

Gauss, Susan. “Made in Mexico: Regions, Nation, and the State in the Rise of Mexican Industrialism, 1920s-1940.” The Hispanic American Historical Review Vol. 92 (2012): 574-575. Print.

Pletcher, David. “The Building of the Mexican Railway.” The Hispanic American Historical Review 30.1 (1950): 26-62. Print.

Rajan, M.S. “The Impact Of British Rule In India.” Journal of Contemporary History (1969): 89-102. Print.

Said, Edward W. Orientalism. New York: Vintage, 1979. 60-80. Print.

Studer, Roman. “India and the Great Divergence: Assessing the Efficiency of Grain Markets in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century India.” The Journal of Economic History 68.2 (2008): 393-437. Print.