As every semester does, this one has come to an end. Students are writing their take home exams, professors are planning summer research trips, and book orders have been submitted for next year.

As I think back across this semester, I’m struck by how different our conversations were than I expected. I’ve taught versions of early American history nearly every election season since 2002. Politicians’ statements about the Founding Fathers usually provide a staple source of discussion in class, particularly when it comes to religion. This semester was different; we had lots of politics to work with, but very little of it had anything to do with religion. Beyond a few tentative moves from Marco Rubio (which I wrote about) and from Ted Cruz (which John Fea has discussed), religion has been mostly absent from the national scene, and the corresponding conversation in class has been about the economy, about race and slavery, and about bigotry, religious and otherwise.

Religion is in the background right now, especially for study of the Founders.  It was the spring of Hamilton, for the culture at large, and for early American historians in particular, who have been continually atwitter about the musical (also @twitter about @HamiltonMusical). One of my favorite songs, for the simple reason that I’ve written about the texts involved, presents Samuel Seabury’s objections to the Continental Congress. Seabury was a Connecticut-born Anglican minister who was educated at Yale and then in Britain before taking up the pulpit in New Yor

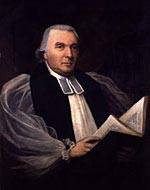

It was the spring of Hamilton, for the culture at large, and for early American historians in particular, who have been continually atwitter about the musical (also @twitter about @HamiltonMusical). One of my favorite songs, for the simple reason that I’ve written about the texts involved, presents Samuel Seabury’s objections to the Continental Congress. Seabury was a Connecticut-born Anglican minister who was educated at Yale and then in Britain before taking up the pulpit in New Yor k. In 1774, when he debated Alexander Hamilton in a series of pamphlets, he was living in Westchester. He rode out the war and went to Scotland in 1783 to be consecrated an episcopal bishop for Connecticut. In 1815, John Adams remarked in a letter to Jedidiah Morse that “the apprehension of Episcopacy contributed . . . as much as any other cause” to American worries about Parliament’s authority. Samuel Seabury became that first Anglican bishop in the United States that Americans were so apparently so worried about.

k. In 1774, when he debated Alexander Hamilton in a series of pamphlets, he was living in Westchester. He rode out the war and went to Scotland in 1783 to be consecrated an episcopal bishop for Connecticut. In 1815, John Adams remarked in a letter to Jedidiah Morse that “the apprehension of Episcopacy contributed . . . as much as any other cause” to American worries about Parliament’s authority. Samuel Seabury became that first Anglican bishop in the United States that Americans were so apparently so worried about.

The on-stage version of Seabury (played by Thayne Jasperson) apparently is not marked as a minister. (I have to say, as a caveat, that I have not seen Hamilton, and since I plan to keep both my kidneys, I can’t imagine ever affording it. Unless Miranda establishes a pair of fellowship tickets for early Americanists, which isn’t a bad idea.) Nothing from the musical’s lyrics tells the listener that Seabury represented not just authoritarian loyalism, but religiously-inspired Anglican loyalism. Of course, Seabury helped this interpretation; he wrote anonymously and did not reference his day job. But the erasure of religious institutions and their representatives, as well as their intertwining with British authority, fits the larger narrative presented by Hamilton. The United States is “young, scrappy, and hungry,” and protected by immigrants. But it fits no where on the Enlightenment-evangelical spectrum that usually dominates study of religion and the Revolution.

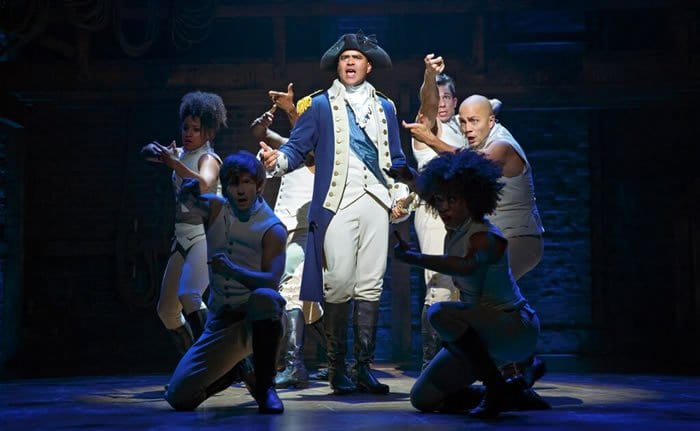

George Washington from the musical “Hamilton,” played by Christopher Jackson

Hamilton’s founders are not particularly deistic or rationalistic, and its story bears little resemblance to that supported by the Christian nationalist types of today either. It is a righteous and gritty Revolution without ideology or faith. And that pretty much seems to match the national conversation right now. “If you stand for nothing, Burr, what’ll you fall for?”

Between Hamilton and Trump, this was a hard semester for the connections I’m used to making between religion, the nation’s founding, and public life. As a citizen I’m actually happy about that, since nothing makes me madder than then sentences that start “the Founding Fathers believed.” As a professor, it made me and the students work a little bit harder. But any interest in the early America is good for business, and Hamilton is a joyous musical romp. And the very BEST part of being a professor is that while the students will move on and take different classes, I get to go back and teach the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries again and again.

Comments are closed.