Today I was very pleased to read Lin Fisher’s great article over at Vox about the perils of historical analogies. It came at the perfect moment, because last Thursday in class I caught myself making too glib comments comparing Samuel F. B. Morse’s nineteenth-century anti-Catholicism and Donald Trump’s anti-Muslim sentiments. Students followed my point easily, but the class and I knew it wasn’t quite right, not least because we need to take Trump’s supporters (if not the man himself) more seriously, both politically and historically. So, today I wanted to backtrack, as we looked at documents from Morse (along with a bit of Maria Monk), and ask the question more seriously.

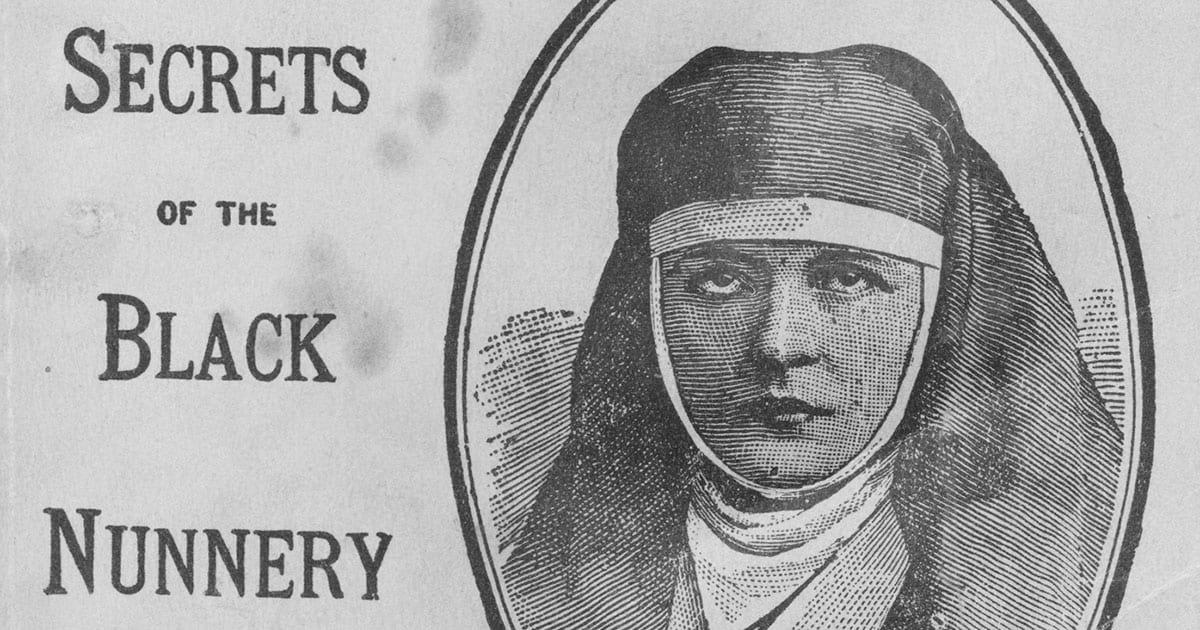

We worked through a variety of questions. What parallels exist between nineteenth-century anti-Catholicsim and the present moment? At first glance, a lot. Fear of a subversive foreign threat, whether a Jesuitical conspiracy sponsored by Catholic monarchies of Europe or terrorists sent by ISIS. At both moments, immigrants are a key part of the conversation. Today they are refugees from the conflict in the Middle East; then they were refugees from famine and revolution in Europe.  In both times, fear rippled through the population that religion, as an essential (primal?) force in people’s lives, would overwhelm any attempted or pretended commitment to the United States. Again in both times, women — nuns, then, and women who wear a head covering, today — played an important symbolic role and were singled out for particular violence.

In both times, fear rippled through the population that religion, as an essential (primal?) force in people’s lives, would overwhelm any attempted or pretended commitment to the United States. Again in both times, women — nuns, then, and women who wear a head covering, today — played an important symbolic role and were singled out for particular violence.

Most productively, however, the students raised a series of questions, things they would have to know about the nineteenth century before they could decide if the analogy would work.

- Was anti-Catholicism condemned in the nineteenth century? Put differently, has increasing the “we” of American religion from just Protestants to Protestants-Catholics-Jews made the country genuinely more tolerant, or merely extended the sphere and maintained the essential prejudice?

- Did nineteenth-century anti-Catholicism lead to law-making at the federal, state or local level? Does the Temperance movement count? For a current parallel, do “security” measures that disproportionately impact Muslims provide a parallel?

- What about violence? What kinds of violence did nineteenth-century Catholics suffer? Was there Catholic on Protestant violence of the same kind?

This last question led to a significant difference, that we explained through changes in technology and communication (always a “black box” in historical change, ironically one that includes Morse): There was no easy nineteenth-century parallel to the problem of Al-quaeda/ISIS claiming to speak for “Islam,” perpetrating very real violence, and the rhetorical problems that emerge from that.

But the real problem, of course, is the one we can’t answer. As a student phrased it: “How bad can it get?” That’s what we want the answer to, and the reality is that history is no guide. The end of the Know-Nothing party didn’t come from a widespread embrace of immigration, it came through the national conflagration of the Civil War. Will this anti-Muslim moment end through distraction by something much greater? Will it end in its own bloody conflagration, whether at home or elsewhere? Will it end, quietly, with the election of someone in the US who can navigate the waters of the present moment carefully? As every historian knows, those are the questions we can’t answer.

Fisher gives us a suggestion of what it can do, however, and this is is powerfully important:

Done well, history gives us perspective; it helps us gain a longer view of things. Through an understanding of the past we come to see trends over time, outcomes, causes, effects. We understand that stories and individual lives are embedded in larger processes. We learn of the boundless resilience of the human spirit, along with the depressing capacity for evil — even the banal variety — of humankind.

The past warns us against cruelty, begs us to be compassionate, asks that we simply stop and look our fellow human beings in the eyes. All of us — grandstanding presidential candidates and partisan tweeting voters — could use a little more of this kind of history, not less.

NB: Those who have seen this blog before will note a different look. The students’ DH work on religion and the American Revolution is up here in its initial form. Explore, send feedback, and stay tuned for the final version!

Comments are closed.