After looking at the American colonies and the different regions, backgrounds, and cultures of each and as a whole, one aspect of early American religion stood out to me more than the rest: the port cities. Early American port cities were major hubs of the economy and politics because of their location. These port cities were the connection to the world outside America and therefore, any news and people coming from Britain had to go through the port cities first. Port cities were places of high activity and were in some of the most populated colonies. I wanted to know how religion was perceived in the early American port cities, mainly Boston, Massachusetts, and Charleston, South Carolina. More specifically, I wanted to research how the literal word of “religion” was used during the time leading up to the American Revolution.

To do this, I first looked at early American newspapers and narrowed my search to the Revolutionary time period, chose a few main sections of newspapers such as Legislative Acts, Shipping News, and Advertisements, and searched only the word “religion.” I put many constraints on the search due to the fact that port cities were large and there was almost too much information to look through. Originally I only wanted to search Boston and Charleston, however, I could not find enough articles to conduct in depth research, so I found a few articles from Newport, Rhode Island, another northern port city. After confining my searches, I found that the word “religion” was connected most often to politics and current governing practices, which makes sense because of my narrowed search fields.

My findings are all seen in the visual (word cloud) which is comprised of the most commonly used words in the articles I found. The larger words are those which were repeated most often. In this word cloud, religion, majesty and excellency (both relating to the King of England), government, general, public, dutiful, society, governor, Boston, Charleston, Peace, Lord, assure, and colony are some of the biggest and most common words. The biggest of these words being religion, majesty, and excellency, is most likely due to the fact I limited my research to Legislative Acts which, during this time period, were mainly addressed through letters. As I found, these letters all used the same format and used the same address to the King and therefore repeated the same words over and over again. Overall, this visual confirms that religion was perceived as political in the port cities.

I also found that religion was used to talk about the colonies, and about the laws being passed in order to the preserve religion and morals of the colonies. This is important because it shows that religion was a part of the discussion of American rebellion and was a prevalent issue during the time leading up to the American Revolution. Furthermore, the articles I found seemed to show, mainly through letters to and from the King of England, that the colonies were not acting in a way that was in accordance with the religion and moral standards of Britain. These articles and letters were being published during the same time that many laws were passed which pushed the colonists to revolt. Although it is difficult to prove that religion was a large part of the American Revolution, it can be proved that religion was at least a part of British discussion of American rebellion and how to stop it.

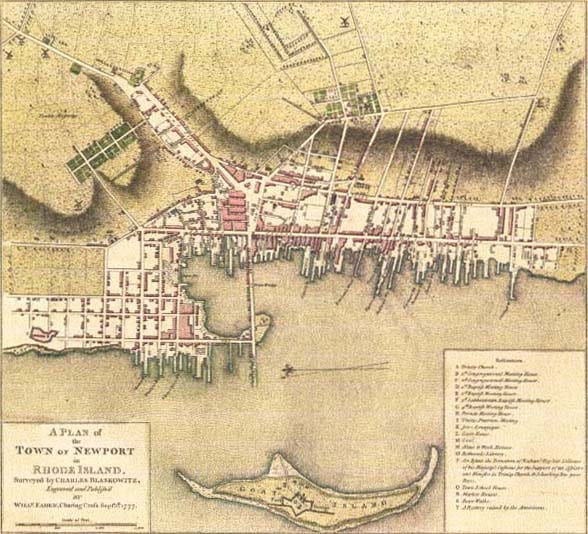

Newport, Rhode Island, 1777

I did not want to ignore what religious institutions formed and made up the port cities, so I decided to look outside early American newspapers and research the society and cultures of port cities. Doing this allowed me to not only determine how religion was perceived, but also allowed me to view other aspects of society apart from politics. Looking strictly at statistical data, I found that in Massachusetts as a whole there were 433 churches and a 13% membership rate, made up of mainly Congressionalist’s and Baptists. South Carolina on the other had 166 churches and an 8% membership rate, made up of mainly Presbyterians, Baptists, and Episcopalians. By looking at this data it is clear that religion was established and a large part of the colonies.

After doing a broad search on the societies of Boston and Charleston, I confirmed that both port cities were large, advancing cities which promoted industrialization, a booming economy, and intense politics. However, these two port cities have very different cultures and societies. Boston, a northern port city centered its economy around elite aristocrats, apprentices, skilled tradesmen and servants. Boston’s society as a whole sought wealth and power, whether through skill, religious leadership, and political influence. As known through American Revolutionary history, Boston saw and created many conflicts leading up to the Revolutionary War. It was here that both the elite and lower classes came together to fight for independence. Charleston, a southern port city differs drastically. Most of its economy centered around its massive plantations which retained both the free and the enslaved. These plantations and the agriculture produced lead to Charleston’s wealth and expanding society. The colony’s founders, influenced heavily by the British, sought to form many towns which contributed to Charleston and South Carolina’s rapid urban development.

Overall, through detailed research in early American newspapers, the literal word “religion” held a political context in the colonial port cities of Boston, Massachusetts; Charleston, South Carolina; and Newport, Rhode Island. Along with its political meaning, religion was present through the establishment of Congressionalist, Baptists, Presbyterians, and Episcopalian institutions. These concluding claims are once again proven in the word cloud which highlights the most frequently used words of religion, Majesty, and Excellency.

For further reference:

“Colonial Massachusetts.” Colonial Massachusetts. Siteseen Ltd, Apr. 2015.

Hart, Emma. Building Charleston: Town and Society in the Eighteenth-Century British Atlantic World. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2010.

Comments are closed.